I think the most common question I get is what political ideology I identify with. More specifically, I get asked about my ideal form of government.

Typically, my one word answer is “nationalist”, but this obviously leaves a lot unanswered. Over the past few years, I’ve gotten a bit less interested in sketching out the particulars of a utopian vision, and more interested in what we can actually do to affect real change.

Still, it is important to have an alternative vision and devote some thought to the ideals we should be aiming at. As nationalists, we are proposing that we have the best vision of how things could be, and we should be able to explain why we have the best answers to some of the perennial problems of politics, especially if we want to attract intelligent people who are thoughtful about these problems. With that said, this is my attempt to explain my worldview as succinctly as possible.

Questions of political philosophy are moral questions. In our time and especially on the radical right, there are people who think they can skip over this fact and answer fundamental questions of political philosophy in a value neutral or “realist” way. They think that by just describing relations like a dispassionate scientist, they can arrive at prescriptions. The irony is that this mode of thought which is typically found among self-described reactionaries is actually a very modern way of looking at politics. I reject this approach and subscribe to the approach of classical political philosophy.

More specifically, I am a Platonist. I reject the naturalist or materialist explanation of the world which is the popular metaphysics of our age. Instead, I am a philosophical monist, and believe the world is an emanation of supersensual ultimate reality, with man’s ultimate end being to transcend his egocentric and partial view of reality and draw closer to ultimate reality in wisdom and love.

I believe the world evolves with an intrinsic drive toward greater unity and integration and I believe man’s primary means of drawing closer to the real is by moral action, love, wisdom, and religious and mystical experience. Universal love is an ideal, but for all but a few mystics the means of expanding our capacity for love and care comes through our particular relationships, through our family and our folk.

The purpose of the state, as I see it, is for a people to secure their existence and allow for the flourishing of these relationships of growth. It is also to foster freedom; not the “negative liberty” cherished by libertarians, but the positive freedom from the internal restraints of ignorance, greed and selfishness. On this Platonic conception of freedom, I cannot do a better job of presenting it than this passage from D. C. Schindler:

"If freedom is conceived in terms of fruitfulness, it will always tend to properly social expression...Law ought to be interpreted itself as an expression of goodness; we might think of it as the extension of freedom into the social sphere. Such an extension is natural to freedom in its original sense, which relates generativity to the notion of belonging to a people.

We might say that the golden thread that binds us to God necessarily passes through others, so that one cannot receive goodness, and so be free, as an individual except as bound to others in community. Indeed, the principal community for Plato is the family, because of its own foundation in nature.

...

The very individualism that Locke understands as the essence of freedom in the political order is just the opposite for Plato...The “root cause of sin,” he says, “is excessive love of self". This excessive love is a disorder, an offense against the good, which is the very principle of generative generosity. But for that very reason, it is a loss of freedom. In short, Plato identifies unfreedom with opposition to the community that law creates.1

Since I believe the purpose of the state is the good life and the collective flourishing of a people, this takes us to the question of man’s nature. These are philosophical questions, but man is a rational animal, and before we sketch out any ideals we must begin with an understanding man’s animal nature. So many of the bad ideas and conflict of our time come from ignoring this and trying to bend human nature to fit political ideals. Part of that nature is to be a tribal, territorial creature with a deep need for community and belonging, and I believe this collective sense is central to politics, since the political is always informed by groups and their interests, friends and enemies.

Sebastian Junger’s Tribe presents historical evidence that shows the profound need for kinship and a common struggle present in humanity across cultures. Some of the examples presented are extraordinary, with records of suicide disappearing and mental asylums emptying during times of national crisis brought about by war:

Psychiatric wards in Paris were strangely empty during both world wars, and that remained true even as the German army rolled into the city in 1940. Researchers documented a similar phenomenon during civil wars in Spain, Algeria, Lebanon, and Northern Ireland. An Irish psychologist named H. A. Lyons found that suicide rates in Belfast dropped 50 percent during the riots of 1969 and 1970, and homicide and other violent crimes also went down. Depression rates for both men and women declined abruptly during that period, with men experiencing the most extreme drop in the most violent districts. County Derry, on the other hand—which suffered almost no violence at all—saw male depression rates rise rather than fall. Lyons hypothesized that men in the peaceful areas were depressed because they couldn’t help their society by participating in the struggle.2

In the 20th Century, we learned a great deal about how genes influence our behaviour, and this brought us the basic insight of genetic similarity theory that we feel more affinity and altruism for those who are more similar to us. Loyalty to one’s ethnic group and ethnic nepotism are each rooted in biology, with “the ethnic phenomenon” having been persistently favoured for its greater adaptive strength over individualism.

These biological underpinnings for ethnic loyalty have important sociological consequences today. There is now a wealth of evidence that increased diversity lowers social trust, leads to a decline in community, and increased alienation and hopelessness for the individual.

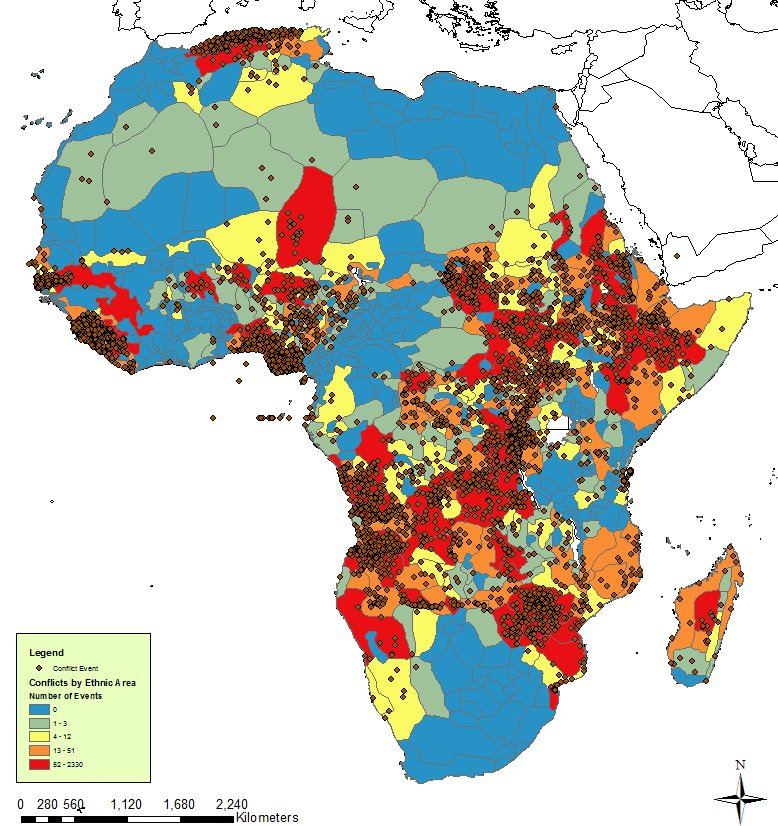

There is an even greater wealth of historical evidence that racial and cultural diversity tends to descend into often brutal conflict. A glaring pattern is that while the world has become more peaceful since the 20th Century and the dominance of liberal internationalism, most of the biggest conflicts since the Second World War, and especially since the end of the Cold War, have been ethnic conflicts. The Troubles, the Balkan wars, the Rwandan genocide, the Ukraine war, and the Israel and Palestine conflict are reminders of the persistence of ethnic strife and the extremes it drives people to.

Modernity has brought increased cooperation and interconnectedness, global capitalism has incentivised countries out of undertaking costly wars, proliferation of defensive military technology has made occupying hostile populations too costly, and international law and cooperation have brought stability to the global system. Yet brutal ethnic conflict persists. Part of the responsibility for these conflicts falls with the politicians, academics and social planners who have imbibed the leftist idea that modernity and interconnectedness will lead to the dissolution of tribal and ethnic loyalties.

This optimism, based as it is in sociological theories that ignore the powerful realities of race and ethnicity, has turned out to be utterly false. Ideologues who believe the ethnic phenomenon to be some kind of false consciousness typically deny the biological reality of race, and have a reductionist economic view that concludes national identities are some kind of false consciousness imposed on the masses by cynical elites. In fact, the phenomenon of nationalism as a popular ideology emerged from the spread of communications technology and literacy — the empowering of the masses and rural populations, who tended to be more nationalistic and have a stronger ethnic identity than the aristocratic and mercantile elites.

Far from stripping away ethnic identity, globalisation and the spread of communications technology has popularised the powerful idea of national sovereignty, while the realisation of a world of other nations and has everywhere been a catalyst for people identifying with and politicising their own ethnic identities. In other words, the ethnic phenomenon isn’t going away.

In recognition of these trends, I believe ethnonationalism is the ideal way to organise the world politically. Ethnonationalism is the belief that the most fair and free state will tend to be the state in which the citizenry share the strongest natural bonds of kinship and culture. Ethnonationalism holds that when a people desires a sovereign homeland to perpetuate their group free of interference, that demand should be respected. I believe this is the best foundation for a political order not just for its facilitating good governance, but because I value cultural and biological diversity, and ethnonationalism allows distinct groups survive and evolve without the conflict created by diversity.

There is a line of thinking on the right that this vision is hopelessly naive, overlooking the realities of power and the inevitable dominance of small nations by an imperial center. Empire has indeed been a reality of history, but little ethnarchies and city-states are just as perennial, and periods of imperial centralisation are typically followed by periods of decentralisation and dispersed sovereignty. In the High Middle Ages, there were as many as 300 independent states and city-states existing at any one time.

I believe the centralisation of the modern period was driven by sociopolitical and military technological trends which are no longer operative, and we are entering another period of disintermediation which will again allow for more dispersed sovereignty.

What about forms of government? Monarchy, minarchy, democracy, dictatorship? Although I view ethnonationalism as a universal framework that can be used to resolve conflict and organise the world, I don’t believe there is any universal ideal form of government, and I think a number of diverse forms attuned to the particular character of a people can flourish. I think the ideal form of government for Europeans is something like Classical Republicanism.

I favour Aristotle’s idea of a “polity” or a mixed regime, combining elements of oligarchy and democracy — an aristocratic republic where sovereignty is entrusted to an elected aristocracy on behalf of the people, managed in such a way as to ensure the preponderance of the aristocratic element and their conducting affairs with a view to the betterment of the people.

Therefore, the ultimate basis of government is popular sovereignty, but this does not mean I favour mass democracy or believe public opinion is infallible. The basis for government is the betterment of the people, but this does not mean the people are not prone to mistaking their true good. The common good of all, not the sum of common desires, is the basis for a Classical Republican notion of popular sovereignty.

In fact, I believe many of the problems of democracy are rather problems of mass democracy, and many of the problems with our modern political systems are due to their great scale. I therefore favour the ideal of the small state, and I believe a guiding principle of good government should be the principle of subsidiarity, which holds that decision making and the provision of services should be kept to the most local, decentralised level possible.

I try to avoid any ideological dogma when it comes to economics. I believe the market mechanism is a tremendously efficient means of allocating resources, but left to itself it often conflicts with the common good, and an excess of wealth inequality is not desirable. I am fine with a paternal state regulating the economy, and I think capitalists must be brought to heel by a strong state to avoid institutional capture by private interest groups. A central goal of economic policy-making should be affordable family formation, rather than simple economic growth targets.

My ideal state would be run on a corporatist economic model. Corporatism is supposed to represent a “third way” between laissez-faire capitalism and communism, where major interest groups representing labour and capital are organised into groups (or corporations) whose representatives engage in collective negotiation to set policy. This model is more ubiquitous than most realise: though as an explicit alternative to capitalism and communism it is most associated with fascist regimes, it was the model for post-war European countries like Austria, the Netherlands and Sweden, and common in Catholic Latin American countries like Argentina and Brazil. Today, a centralised variant of corporatism is the basis for the Chinese economic model.

I have discussed this in a rather abstract way, but the particulars matter. What I am laying out is a universal particularism — a universal normative framework by which we can establish an order to foster our own particularist loyalties and affinities. I am an Irish nationalist, and an advocate for my extended European family. All white nations are today under extreme threat due to mass immigration and low birthrates leading to demographic replacement in their historic homelands. As a people, we are tolerating this due to our embrace of liberalism, egalitarianism and anti-white narratives used to engender guilt in our race.

I believe the most momentous change of our age is this great demographic transformation, which will have terrible consequences for our own people and the world. I believe it is the duty of every European to resist this by awakening other members of his race and working for political change, toward states which again work to secure our collective future and flourishing. That is why I have devoted the best part of my life to this task.

Schindler, David C. Freedom from reality: the diabolical character of modern liberty. University of Notre Dame Pess, 2017.

Junger, Sebastian. Tribe: On homecoming and belonging. Twelve, 2016.

Excellent stuff man!

What nation today do you believe comes closest to realizing your vision of an ideal society?