Is modern society too big? This is not the kind of question we are used to approaching political theory with. We ask a lot of questions about the ideal form of government, but very little about the ideal scale of a society. This is not to be confused with establishment conservatives complaining about the size of government itself, promising that all manner of problems can be solved by eliminating taxes, easing regulations and laying off bureaucrats. The question concerns not the size of the government apparatus, but rather the society it governs. My last essay looked at the work of Panagiotis Kondylis, and his view that we are in a unique social formation called mass democracy, characterised by mass consumption and production, atomisation, managerialism and globalisation. All of these are unique to mass society, so it may be worthwhile to take another look at what political philosophers have written about this.

In contrast to contemporary politics, many of the great political philosophers of history converge on the small, organic state as the ideal unit for their political theories. Kirkpatrick Sale describes this perennial pattern in what he calls “the decentralized tradition”:

It is striking to re-read history with eyes opened to the persistence of this tradition, because at once you begin to see the existence of the anti-authoritarian, independent, self-regulating, local community is every bit as basic to the human record as the existence of the centralized, imperial, hierarchical state, and far more ancient, more durable, and more widespread.1

When we read about the great political philosophers of antiquity, we make the mistake of assuming that their notions about forms of government, like democracy, are the same as ours today. We often neglect to consider the scale these thinkers had in mind for implementing these ideas : the small, compact, homogeneous city-state. And this was not just a reflection of their own circumstances. They often emphasised limits to the size of a society, and gave clear reasons for these limits.

Aristotle warned that there is to the size of a state “a limit, as there is to other things, plants, animals, implements; for none of these retain their natural power when they are too large”. The city’s final end, according to Aristotle is to cultivate man’s natural capacity for reason and direct him toward the good life. With this in mind, the city should be large enough to be materially and spiritually self-sufficient, with enough diversity of opinions and types of men to encourage dialogue and moral reasoning. Aristotle warns against imposing too great a unity on the city, believing that the prescriptions of Socrates and Plato would stifle moral development. But, Aristotle warns of a limit to diversity which would disrupt the purpose of the city. Empires are too large and heterogeneous to make virtue the purpose of their politics. A communitarian ethos is not possible in an Empire made up of diverse groups and belief systems.

Book VII of Aristotle’s Politics seeks to determine some of the features of the ideal state, including the ideal population size. He writes:

Experience shows that a very populous city can rarely, if ever, be well governed; since all cities which have a reputation for good government have a limit of population. We may argue on grounds of reason, and the same result will follow. For law is order, and good law is good order; but a very great multitude cannot be orderly: to introduce order into the unlimited is the work of a divine power- of such a power as holds together the universe. Beauty is realized in number and magnitude, and the state which combines magnitude with good order must necessarily be the most beautiful.2

Aristotle writes that the ideal size of a polity is “the largest number which suffices for the purposes of life, and can be taken in at a single view.” This is obviously far smaller than any of our modern nation-states, corroborating Aristotle’s belief in the city-state as the ideal unit of society, though even the city-states of Aristotle’s Greece probably didn’t have populations small enough to be “taken in at a single view”. Why does Aristotle feel this kind of limitation is necessary? Firstly, Aristotle says it is imperative for everyone in the polity to have some familiarity with one another to enable selection of governors based on merit. Secondly, Aristotle warns that if a society is too big, foreigners “will readily acquire the rights of citizens”. One commentator elaborates on Aristotle’s belief in the natural limits to state capacity:

Expansionist or globalizing regimes reflect ontological confusion: they wrongly elevate the category of quantity over that of substance, and thus the infinite over the finite. As a consequence they are doomed to catastrophe. By contrast, the ideal city, resolutely local, affirms its own limitations. It is an organic whole whose parts are properly organized. As in a healthy organism, that which is fit to rule will issue commands, while that suited to be ruled will obey.3

Aristotle’s mentor, Plato, was even more specific in his prescriptions for the ideal size of a society, even providing an ideal number of citizens. In Laws, Plato puts this number at 5,040. This specific number was selected and revered due to multiple numerological and religious considerations; since it is divisible by twelve, like the twelve gods of the Pantheon, it would place the City under the protection of the gods. But Plato’s selection of a number roughly this size was motivated by a belief that an optimal population size would safeguard against decadence and other causes of social discord which had plagued city-states such as wealth inequality, since the land of the city could be divided equally among families. A number of this size was also ideal because it was just small enough to allow citizens to recognise one another, but large enough to ensure the state could defend itself against outside threats and assist other cities.4

This kind of search for an ideal population size is not unique to the ancients. Thomas More’s Utopia held 6,000 citizens. Charles Fourier, an influential 19th Century socialist, proposed Phalanstère: buildings for self-sustaining utopian communities consisting of 500-2,000 residents. The same number was proposed by Robert Owen in his imagined “villages of co-operation”.

Saint Augustine, rivaled only by Thomas Aquinas in his influence on shaping the philosophy of Western Christianity, condemned a certain kind of imperialism in his City of God. He does, however, defend the ideal of the commonwealth, referring specifically to the Roman Empire as an Empire which, at least at one point, was ruled by men motivated by justice. In book IV of The City of God, Augustine strongly condemns Ninus - an Assyrian King who disrupted the natural boundaries of nations in the East as the first invader of ancient monarchies- using him as an example of how empires are founded on force and a lust for power which he denounces as criminal:

to make war on your neighbors, and thence to proceed to others, and through mere lust of dominion to crush and subdue people who do you no harm, what else is this to be called than great robbery?

Still, Augustine considered the ongoing fall of the Roman Empire a great tragedy, and defended its own historic expansion as having arisen originally through just wars. He values the Roman Empire precisely because its hegemony provided such peace and stability, but he points to a world of micronations as an ideal and condemns the tyranny of powerful nations over weaker ones.

Augustine:

hazards the conjecture that the world would be most happily governed if it consisted, not of a few great aggregations secured by wars of conquest, with their accompaniments of despotism and tyrannic rule, but of a society of small States living together in amity, not transgressing each other's limits, unbroken by jealousies. In other words, he favoured a League of Nations - a condition, as he put it, in which there should be as many States in the world as there are families in a city.5

Jean-Jacques Rousseau also devoted great thought to the problem of scale. Human unfreedom is rooted in mass-society’s division of labour making us reliant on the economic system and enslaving us to desire. Rousseau’s ideal is to avoid this unnatural state by remaining in “natural” communities. But, since this is only possible for a few, Rousseau’s solution is the restructuring of this dependent relation into a Republic which expresses the General Will. Despite us losing the primitive freedom offered by natural societies, we can yet realise a positive freedom by aiming at the common good.

One Rousseau scholar calls these paths the model of the tranquil household and the model of the Spartan City.

The road away from nature might have led man to Spartan virtue or to domestic bliss. In actuality he chose civilization, a condition in which neither duty nor felicity is possible.6

Rousseau agrees with ancient political philosophers on the ideal of the Greek pólis - he chooses Sparta over Imperial Rome. In his own time, rather than France or Switzerland it was his own little city-state of Geneva that he was seeking to save from despotism. Sparta, for Rousseau, was the ultimate expression of his belief that a civic ethos could stand above private interests and instil a discipline in people that could be for everyone’s good. It may seem odd that a philosopher associated with liberalism and democracy would celebrate Sparta, but Rousseau is a more complex and conservative thinker than his critics give him credit for. Rousseau said there were two key principles of the Social Contract: that sovereignty ultimately rests in the hands of the people, and that aristocratic government is the best of all. While democracy and equality may be natural to us, and Rousseau celebrated this natural state, within a civic order the move toward pure democracy away from an aristocratic republic is a degeneration. The value of the civic order is its transformation of our self-love into virtues of citizenship and patriotism which inculcate in us a sense of duty. For Rousseau, Sparta was the ideal of the society with the perfectly socialised man: citizens totally devoted to their social role over their self-interest. Duty to the social unit could be so transformative that mothers become indifferent to the death of their sons on the battlefield.

In order to cultivate this kind of selfless devotion to the polity, Rousseau believed it was necessary for citizens to nurture a sense of pride, patriotism. And for this, it was important that their society have the proper scale. Like Aristotle and Plato, Rousseau agrees that citizens should be personally familiar with one another. Past a certain scale, people will become disinterested in what is happening to their fellow man, and even if they care, they will necessarily feel a sense of powerlessness as their voice is shown to matter little. Citizenship is prefaced on a shared sense of common interests, and this feeling can only be inculcated by a certain sense of pride and kinship. And so Rousseau ends up advising that:

The small, isolated city, the peasant republic, its opinions and mores carefully instilled by a Legislator and maintained by patriotic feeling, is the sole defense against civilized tyranny.7

Rousseau agrees with Aristotle that the size of the state should be large enough to guarantee the self-sufficiency of the community and to reproduce and defend itself, but not so large that it cannot sustain itself off the land. This would obviously be determined by a number of environmental factors unique to each land and people. Rousseau neatly outlines the many advantages of small states as follows:

The size of nations, the extent of states: this is the first and principal source of the misfortunes of the human race, and above all of the innumerable calamities that sap and destroy civilised peoples. Practically all small states, no matter whether they are republics or monarchies, prosper merely by reason of the fact that they are small; that all the citizens know and watch over one another; that the leaders can see for themselves the evil that is being done, the good they have to do; and that their orders are carried out before their eyes.8

Interestingly, Rousseau was asked to apply his Republican principles to an existing nation-state in his own time, which was far beyond the size he recommended as ideal. Considerations on the Government of Poland was Rousseau’s last work of political theory, and his disposition seems far more conservative than in his more theoretical writings. What’s most interesting is that he proposes for Poland the ideal of a confederation of 33 smaller states:

If Poland were, according to my desire, a confederation of thirty-three States, it would unite the strength of the great Monarchies and the liberty of the small Republics; but for that, it would be necessary to renounce ostentation, and I am afraid that this article is the most difficult.

Rousseau considers a confederation of small states as ideal for combining the advantages of monarchy and the liberty afforded by living in a small homogeneous community. The confederation could protect Poland from outside threats, while the decentralisation to many smaller entities would promote representative government and civic virtue. Rousseau’s compromise is federalism. A confederation of small states is desirable, but guaranteeing the unity of the Polish nation, with a common education system and sense of patriotism, is a more realistic way to safeguard the virtues Rousseau values. Rousseau demonstrates that a consideration for realpolitik trumps his idealism in his recommendations for Poland. In the long run he believes the atomising civilizational process can only be slowed by the maintenance of small states which can maintain their identity by virtue of their smallness and homogeneity, like the Swiss city-states he admired.

Even more than Rousseau, Montesquieu devoted great attention to the question of scale as it concerned republics and agreed with classical political theorists that an excess of wealth was incompatible with virtue. He warned that in a large republic, “men of large fortunes, and consequently of less moderation” have greater power at their disposal to oppress their fellow citizens. Large states not only have a diversity of interests, but also greater wealth disparities - this means private interests will increasingly diverge from shared interests, leading to an erosion of civic virtue which eventually makes a republic unworkable. Not only will the willingness to work for a common goal be eroded, but the ability to even conceive of such a goal disappears in large, unequal societies.

Even the genuinely public-spirited citizen will not be able to comprehend all the variety of facts and conditions that yield a public good in a state that contains commerce and agriculture, great urban ports and remote mountain villages, rich and poor. Even the virtuous will tend to mistake the interests of their own region for the interest of the whole, or simply be overwhelmed by the attempt to understand the whole.9

Montesquieu was also concerned with the potential for despotism created by large states. Both the Roman Republic and the English Commonwealth had descended into strong military dictatorships. For Montesquieu, this was no accident. The large militaries that come with large states tend toward strong, concentrated executive power, which is ideally fulfilled by a dictator. If none exists, the same military is likely to provide a candidate in the form of a popular general. Montesquieu writes in his Considerations on how successful militaries can erode civic virtue and embolden potential despots, using the Roman military as an example. Once Rome extended beyond the boundaries of the Republic, soldiers came to identify more with their commanders than the state, and the granting of Roman citizenship to newly conquered territories weakened feelings of patriotism:

When the legions crossed the Alps and the sea, the warriors, who had to be left in the countries they were subjugating for the duration of several campaigns, gradually lost their citizen spirit. And the generals, who disposed of armies and kingdoms, sensed their own strength and could obey no longer. The soldiers began to recognize no one but their general, to base all their hopes on him, and to feel more remote from the city. They were no longer the soldiers of the republic but those of Sulla, Marius, Pompey, and Caesar. Rome could no longer know whether the man at the head of an army in a province was its general or its enemy.10

Like the other theorists mentioned, Montesquieu recognises that the main obstacle to the ideal of small republics is the need for defence from outside threats. Yet it is the growth of the military which ends up becoming one of the main threats to the maintenance of such a state.

Montesquieu’s thought led to a revival of classical Republicanism, and his arguments that Republicanism necessitated small states became orthodoxy for a period (American Anti-Federalists drew extensively on his work). In his own period and like Rousseau, Montesquieu had an affinity for the model of 18th Century Switzerland and its confederation of small states. For the advocates of decentralisation and small-states, Switzerland has proven to be a popular example to point to, right up to the present day.

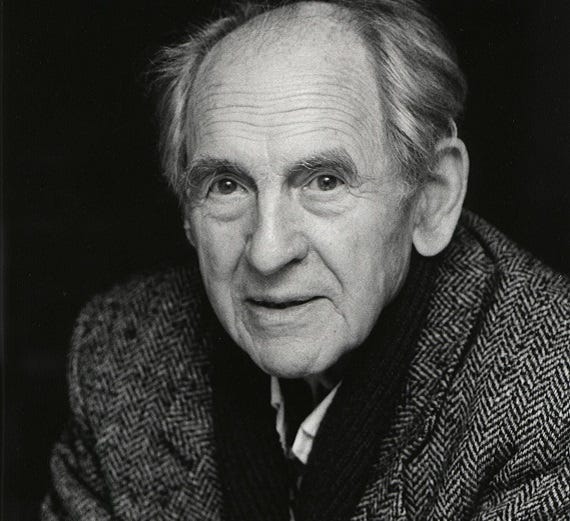

In the 20th Century, one of the great advocates of small state governance was Leopold Kohr, an Austrian economist and political theorist. In both economics and politics, Kohr railed against “the cult of bigness”. His first published essay, Disunion Now - A Plea for a Society based upon Small Autonomous Units, laid out his vision of a Europe of hundreds of small states, drawing again on the Swiss example to demonstrate how his vision could succeed. His three most popular books, The Breakdown of Nations (1957), Development Without Aid (1973) and The Overdeveloped Nations (1977) all built on this vision and developed Kohr’s idea that most social problems could be solved by reducing, dividing and decentralising modern societies into smaller units. To Kohr, “There seems to be only one cause behind all forms of social misery: bigness.”

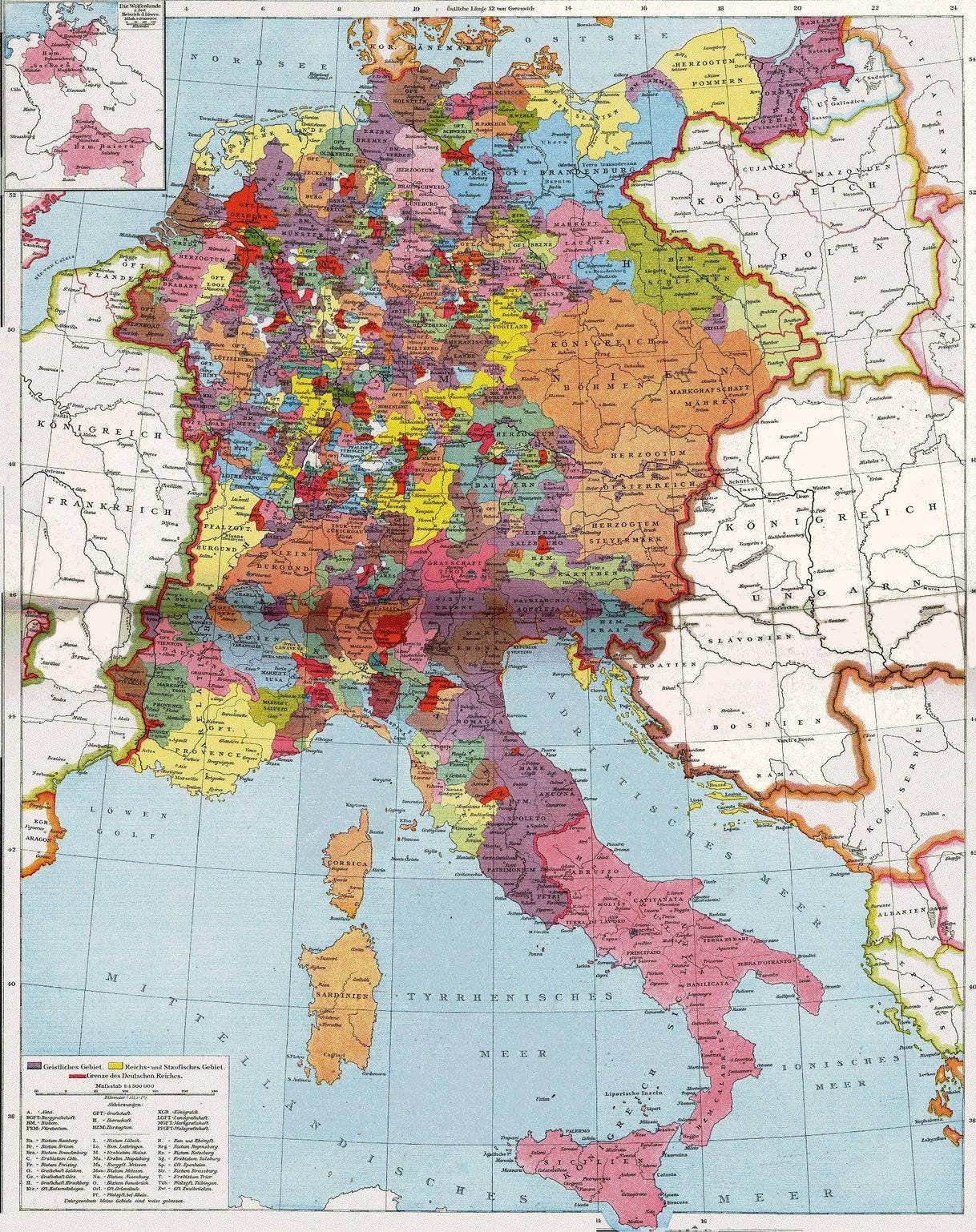

Kohr’s essay Disunion Now was written in 1941, at a time when social planners were talking about the need for global organisations and fewer nations as the alternative to the nationalism that had plunged Europe into a second World War. Kohr was almost a lone voice preaching to the world that the answer was in fact more states - more nations. The planners whose vision would be realised in the European Union were also looking to Switzerland, but as an example of a great unification of smaller, petty nationalisms. Switzerland had united French, Italian and German speakers harmoniously. While conflicts between these nations tore Europe apart, Switzerland demonstrated the possibility of setting aside differences and national rivalries and promoting cooperation for prosperity within the same borders. Surely this proved that the warring nations of Europe could be unified by a larger supranational entity? But Kohr took a different lesson. Switzerland was about 70% German. If it had been a true democratic unification, the Germans would have dominated the other groups. What then, was the real lesson to take from Switzerland?

In fact the basis of the existence of Switzerland and the principle of living together of various national groups is not the federation of her three nationalities but the federation of her 22 states, which represent a division of her nationalities and thus create the essential precondition for any democratic federation: the physical balance of the participants, the approximate equality of numbers. The greatness of the Swiss idea, therefore, is the smallness of its cells from which it derives its guaranties. The Swiss from Geneva does not confront the Swiss from Zurich as a German to a French confederate, but as a confederate from the Republic of Geneva to a confederate from the Republic of Zurich.11

Kohr’s radical proposal was to divide Europe into many small states of roughly equal size, which would ensure a perpetual balance of power and peace. The alternative, he warned, was a European federation which would inevitably become dominated by Germany due to their simple numerical advantage. Kohr suggested that Germany could be split up into the historical German states. In fact, all of Europe still contained the basis for very natural divisions into smaller states, precisely because this condition had been so natural and successful a state of affairs for Europe for centuries. Instead of a Europe of Poland, Spain, Germany etc. Kohr imagined a European map that looked more like the Middle Ages:

Aragon, Valencia, Catalonia, Castile, Galicia, Warsaw, Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia, Ruthenia, Slavonia, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Macedonia, Transylvania, Moldavia, Walachia, Bessarabia, and so forth.

From this extensive list, one fact emerges already now. There is nothing artificial in this new map. It is, in fact, Europe’s natural and original landscape. Not a single name had to be invented. They are all still there and, as the numerous autonomy movements of the Macedonians, Sicilians, Basques, Catalans, Scats, Bavarians, Welsh, Slovaks, or Normans show, still very much alive. The great powers are the ones which are artificial structures and which, because they are artificial, need such consuming efforts to maintain themselves.12

Unlike other theorists, who made rather straightforward pragmatic arguments about the effects of scale on the stability of republics, Kohr believed himself to have discovered a universal principle of order which he was merely applying to the political sphere. Summarised in a sentence: “When something is wrong, something is too big.” Kohr first explores this philosophical argument in The Breakdown of Nations, where he observes an ordered universe built on a manifold of simplicity. Past a certain size, we observe that everything collapses or explodes. Kohr believed most order is the result of “mobile balance” in nature - inconceivably complex, emergent patterns of behaviour from the dynamic interplay of small organisms, each with their own agency. If we look at how stability and freedom are balanced in nature, we can draw lessons which apply right up to the scale of devising a successful international order.

Kohr’s Democratic Argument

Kohr argues that a small state will tend to secure greater freedom and sovereignty for the individual, which is necessarily more democratic. Kohr asserts this as true regardless of whether the state in question is a republic or a monarchy. This is because, regardless of the form of government, there is less separation of the government from the people, and a more immediate relationship of service where citizens are too close to their rulers to lose touch with their purpose. A monarchy of a small statelet like Lichtenstein is far more democratic, Kohr reasoned, than a “democracy” like the United States, where citizens may be separated from their ruler by thousands of miles, their voice diluted by the millions of others of their giant state. Many of the greatest tyrant’s arose from large republics and democracies, proving that the issue of tyranny is more a problem of large states than any system of government.

Here it is important to differentiate between democracy and mass-democracy. The kind of democracy philosophers like Aristotle and Rousseau talked about were so different from the democracy of modern mass-states that all of the traditional debate around democracy collapses at the mass level. In mass democracies most individuals are checked out, politically apathetic and ignorant, and rule is exercised by various special interest groups, political parties, mass media and informal arms of the state.

It is these latter rather than the individual who become increasingly the true agents and asserters of political sovereignty, so that we should speak of a group or party democracy rather than of an individualistic democracy. 13

Mass democracies must serve society; the mass man. Their scale allows them to generate general improvements only through homogenisation, or, as Kohr describes it, “totalitarian uniformity”. The individual is stripped of agency, becomes a tool of manipulation for the social planners, and is moulded to judge success and progress only in quantitative terms. GDP, consumer spending, economic expansion and population growth become the signs of a successful society. Mass man does not heed Aristotle’s warning, and confuses a populous state with a great one.

Kohr’s Cultural Argument

Kohr argues that massive states are culturally barren, impressive only in raw physical strength., But “Man’s life lies in the spirit, and the spirit can develop only in the unoppressive shelter of a small society.” Kohr argues that the historical record supports this contention. But how? Firstly, politics and military affairs are altogether less glorious in small states, and the path to exercising great will to power through conquest is limited. Great men are thus more inclined to direct their energies to cultural achievements. The limit on expansion also redirects the ambitions of rulers, who seek to leave their mark by offering patronage to the arts and other cultural pursuits. The arrangement of a world of small states is also conducive to cultural creativity due to the relations between states. Heterogeneity allows for a number of distinct paths to be followed and experimented with, while the multitude of sovereigns also creates healthy competition which fuels creative achievement. Once again, Kohr believes his faith in the productivity of this model is perfectly demonstrated by the historical achievements of Europe:

To realize this we need only glance at Europe’s countless little cities. It is there, not in the great metropolitan additions in which some of them have been drowned, that we find the main part of our cultural heritage, since nearly every little city has at one time or other been the capital of a sovereign state. The overwhelming number, splendour, and wealth in palaces, bridges, theatres, museums, cathedrals, universities, and libraries we do not owe to the magnanimity of great empire builders or world unifiers, who usually prided themselves on their ascetic modes of life, but to those ever-feuding rulers who wanted to turn their capital into another Athens or another Rome. And since each of them imposed the imprint of his particular personality on his creations, we find, instead of the giant dullness and uniformity of later colossalism, as many fascinating differences in architectural pattern and artistic styles as there were rulers and little states.14

In contrast, the intellectual development of mass society becomes focused on efficiency, output and material progress. Cultural output and the direction of funding becomes aimed at mass consumption and maximising profit. The monuments of mass society are utilitarian, inoffensive and sterile. No better example exists of the cultural productivity of the small state than the Greek city-states, and their wealth of genius philosophers, poets and scientists. Even England, Kohr argues, produced the bulk of its literary geniuses - Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, Thomas Lodge - when it was a relatively insignificant nation-state of about 4 million people, and, writes Kohr:

It is no coincidence that many of the most eminent and fertile contributors to modern English literature, Shaw, Joyce, Yeats, or Wilde, were Irish, members of one of the world’s smallest nations.15

It is a similar story when we look at the achievements of continental titans like Italy and Germany:

The mess of states that were Naples, Sicily, Fiorense, Venice, Genoa, Ferrara, Milan, produced Dante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Tirian, Tasso, and hundreds of others of whom even the least outstanding seems greater than modern Italy’s greatest artist, whoever that may be. The Mess of states that were Bavaria, Baden, Frankfurt, Hesse, Saxony, Nuremberg, produced Goethe, Heine, Wagner, Kant, Dürer, Holbein, Beethoven, Bach, and again hundreds of whom the least known seems to outrank even the greatest artist of unified Germany, whoever that might be.16

Kohr laid out a way in which his vision of a Europe of small states could be made politically viable, namely, through a proportional representation, European federal system which would disperse political power to smaller districts. Kohr believed these districts, which could correspond to historical divisions, would gradually cultivate the reemergence of historic ethnic identities and remove the power of major urban centers to dominate national culture and subject other regions to their economic demands. However, Kohr was anything but optimistic about Europe choosing to reform itself in the way he desired. Chapter 11 of The Breakdown Of Nations is titled “But Will It Be Done?” and contains a single word: “No!” Kohr instead predicted a bipolar world of the Soviet Union and the American Empire (he may have been one of the first to use that term) heading inexorably toward war, and eventually, the creation of a universal state. Yet his study of history made him confident that these periods of intense centralisation would naturally be followed by the return to a more natural, less centralised order:

After a period of dazzling vitality, it will spend itself. There will be no war to bring about its end. It will not explode. Like the ageing colossi of the stellar universe, it will gradually collapse internally, leaving as its principal contribution to posterity its fragments, the little states-until the consolidation process of big-power development starts all over again.17

Sale, K. (2017). Human scale revisited: A new look at the classic case for a decentralist future. Chelsea Green Publishing. Pg. 219

Barker, E., & Stalley, R. F. (1995). Aristotle: Politics. Book VII, Part IV

Roochnik, D. (2012). Retrieving Aristotle in an age of crisis. State University of New York Press.

Plato, P. (2016). Laws. Xist Publishing., 737d, 738e

John Neville Figgis, The Political Aspects of St. Augustines ‘City of God’, pg. 58

Judith Shklar, Men and Citizens, Pg. 33

Shklar, J. N. (1985). Men and citizens: a study of Rousseau's social theory. CUP Archive. Pg. 175

Shklar, J. N. (1985). Men and citizens: a study of Rousseau's social theory. CUP Archive. Pg. 11

Levy, J. T. (2006). Beyond Publius: Montesquieu, liberal republicanism and the small-republic thesis.

Montesquieu. (1999). Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline (D. Lowenthal, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Hackett Publishing. p. 91

Kohr, L. (1992). Leopold Kohr on the Desirable Scale of States. Population and Development Review, 18(4), 745–750.

Kohr, L. (2017). The breakdown of nations. Bloomsbury Publishing. Pg. 57 & 58

Kohr, L. (2017). The breakdown of nations. Bloomsbury Publishing. Pg. 100

Kohr, L. (2017). The breakdown of nations. Bloomsbury Publishing. Pg. 118

Kohr, L. (2017). The breakdown of nations. Bloomsbury Publishing. Pg. 126

Kohr, L. (2017). The breakdown of nations. Bloomsbury Publishing. Pg. 127

Kohr, L. (2017). The breakdown of nations. Bloomsbury Publishing. Pg. 216

This could also be highly useful for reinvigorating religion as large states tend to despise it as a challenge to their authority, but smaller states would be more likely to see it as something to unite around in a healthy way.

Good post; thank you. I often wonder whether the advance of technology has made it impossible to live in human-sized communities, or whether that is a fear propagated by the technocrats.