Does Ireland have a notably lower IQ than the rest of Europe? This is a common belief, especially in circles where discussion of the topic of race and IQ is common. Low Irish IQ is often taken for granted, and used to explain phenomena like Ireland’s historic economic backwardness and anti-Irish attitudes to places they immigrated to. Where did this belief come from, and what do we actually know about Irish IQ?

The claim of low Irish IQ was first popularised by Hans Eysenck, a German-born psychologist who spent his career in England. Eysenck first referenced low Irish IQ in his 1971 book Race, Intelligence and Education. Eysenck did not believe in substantial racial differences in IQ, but maintained that there were specific groups of Blacks with lower average IQ than certain White groups, referring particularly to African-Americans compared to White Americans. Eysenck believed this gap could be explained by lower-intelligence Blacks having been selected from Africa to be sent to North America as slaves. To support this theory - and perhaps to soften the blow of discussing intelligence differences between races - he pointed out that the same difference could be observed between the Irish and English. Whereas in the case of Africa, the worst among them were sent as slaves to America, in Ireland it was the best, brightest, and most ambitious who left in search of a better life, causing a lowering in the average IQ of the remaining Irish.

To back this up, Eysenck drew on data collected by John McNamara (1966) to show that Irish schoolchildren scored 15 points lower than their English counterparts - the same gap that existed between White and Black Americans. In 1966, MacNamara administered the Jenkins Nonverbal Reasoning Test to 1,083 Irish schoolchildren, in a study intended to examine the effects of Irish/English bilingualism on the children’s learning outcomes. MacNamara himself subsequently disavowed the conclusions drawn by Eysenck and explained his belief that the testing he carried out was not a good reflection of national IQ. MacNamara cited two main reasons: the children’s unfamiliarity with this kind of testing, and the translation from English to Irish affecting the children’s understanding of instructions:

This intelligence test was the first printed test these 1083 children had ever seen and moreover the test contained a variety of visual puzzles that few had ever seen before. I suspect the test scared a number of them witless.

Besides, in attempting to translate the instructions of the test to Irish for the native speakers of Irish I found that slight changes in wording produced large changes in the scores obtained on the set of accompanying items. It seems that difficulty in following the written instructions could have a marked effect on children's level of success. The whole study showed that the Irish children were poor readers of English. Little wonder when English reading was neglected for Irish reading in the primary-school curriculum of this period.1

Because MacNamara's study was designed to address bilingualism, a sizable proportion of students from Irish-language schools, who had never seen a standardised test, were deliberately included. But this made his overall sample inappropriate for comparison with students from England where the test had been standardised and language was not a confounding factor. MacNamara points out that since his testing in the late 1960s, more stress was placed on English reading comprehension in the Irish school curriculum, and Irish children were now (this was written in 1988) scoring marks on English reading tests on par with English students – proof for MacNamara that the great IQ gap between them was never there to begin with.

But what about MacNamara’s claim that unfamiliarity with standardised tests affected the student’s results? Reading that students were “scared witless” by a simple test, one would be forgiven for casting a suspicious eye on MacNamara. Perhaps he is motivated here, even unconsciously, by an understandable patriotic urge to redeem his countrymen in the eyes of the world, having provided the material for their singling out as mentally deficient by English academics.

Though he doesn’t reference it himself here, earlier research by MacNamara suggests he was correct. In 1964, MacNamara carried out another study on Irish schoolchildren where the students took six different versions of an IQ test over a three week period. The average IQ increased on each test by an average, of 1.2 points, until it reached 96.13.2 This is a significant increase, and since, as MacNamara claims, the Irish speaking students in his later research had no experience with standardised testing of any kind, not just IQ, we would presumably expect the inhibitory effect of unfamiliarity with testing to be much greater.

Eysenck repeated his claim of a substantial IQ difference between Ireland and England again in his 1981 book Intelligence: The Battle for the Mind. This time, Eysenck draws on research carried out by Richard Lynn, who collected data to break down IQ scores by region within the British Isles, finding that:

London and South-East England have the highest mean IQ score (102), and the Republic of Ireland the lowest (96). This difference of 6 points is highly significant, from a practical as well as a statistical point of view

Eysenck was happy to draw on Lynn, for Lynn also explains this difference as caused by selective emigration creating a brain drain on Ireland. However, Lynn’s score of 96 is far higher than the 87 Eysenck earlier claimed, which had placed the Irish on par with American Blacks.

Lynn based his score on a study of 3,466 Irish children aged 6 to 13 using a Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices in the 1970s, by Enda Byrt and Peter Gill. The scores were weighted against a British mean, and calculated at 97. Lynn then adjusted for the fact that the Irish children were two months older than the British standardisation sample by revising the estimate down to 96. I find no reason to reject this study, though it would be easier to embrace it if its full methodology were available for public viewing. Regardless, the three point deficit on the British mean is hardly warrant for the low IQ label (Lynn estimated Scotland and Wales’ IQ to be 97). In drawing on Lynn’s data, Eysenck compared it with what Lynn found to be the highest IQ region studied – London and Southeastern England – to point out that the Irish were trailing by 6 points, double the difference between Ireland and the British mean. Presumably Eysenck focused on this larger gap because a 3 point difference would have seemed insignificant enough to seriously undermine previous claims he had made about the Irish IQ gap.

A source of confusion here is that Lynn later cited the testing done by Byrt and Gill to establish an Irish IQ of 88, corrected to 87. In IQ and the Wealth of Nations, Lynn wrote:

In 1972, norms for the Standard Progressive Matrices were obtained for a sample of 3,466 6- to 13-year-olds. The data are given by Raven (1981). In relation to the 1979 British standardization sample, the Irish children obtained a mean IQ of 86. Because the Irish data were collected seven years earlier, this needs to be raised to 87.

Lynn then claims this same testing suggested an IQ score of 88 in a 2015 paper.3 The original thesis is not available anywhere for viewing except in the University College of Cork library, and most citations of it just go back to Lynn’s interpretation. This figure of 87 is often cited in discussion of low Irish IQ, for example Ron Unz cites it to argue there has been a dramatic increase in Irish IQ since the mid-20th century due to environmental factors.4 Seeking clarity, I contacted Peter Gill, one of the co-authors of this research. Gill explained to me why their research was still the best conducted on Irish intelligence. The following is taken from my e-mail exchange with him (published with his permission)

You ask? We were Masters students. We contacted and co-operated with John Raven (son of Raven's Matrices). At the time he was a research at the ESRI (Economic & Social Research Institute, in Dublin). We also contacted IBM/Microsoft in Dublin, who agreed to help us. We were "assigned" a staff member who helped us create a data file (almost unique at the time) of the pupils responses, as marked on Raven's and Mill Hill forms, using, also for the first time (in this context), optical reading technology. Thus, the qualitiy of our data, in comparison with practice at the time (paper and pen, with transfer to files by hand) was exceptional.

Then there was our sample. I would argue that this was also unique. We cooperated with the Irish Department of Eudcation, who supplied us with a data file (magnetic tape) of ALL national schools in Ireland. We took this to Microsoft who helped us draw a perfect random sample (with the 4300 schools stratified by size).

And then, uniquely, in an international context (of sampling of school pupils), we got the co-operation of all principals/managers to draw a proportionate random sample of pupils within each school (from school rolls). We had NO non-response at school-level, and NO non-response at pupil-level (except for those pupils who were absent on the day of testing (I did a separate study on this data: <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0031383770210107>

So, I would argue, irrespective of results, our sample was completely superior to those used in Eysenck's and Lynn's arguments.

Unfortunately, there is no Online version of our rebuttal of the "bullshit" (Byrt and Gill, Eysenck and the Irish IQ, The Education Times, 1975) - I have a photocopy of this text.

The photocopy Gill sent me is of a rebuttal he and Byrt wrote to Eysenck’s claim of a low Irish IQ comparable to African-Americans, drawing on their own research. The article is titled “Eysenck and the Irish IQ: The evidence that proves him wrong”. In it they assert that

The performance of Irish schoolchildren does not differ significantly from that of British schoolchildren when samples are matched as closely as possible.5

Looking at the tables they produced comparing their Irish results with a British sample, there is very little difference until the ages of 12 and 13, when the Irish students suddenly start to significantly trail the English sample. They explain this was the result of a “piling up” of less able students, with their more intellectually gifted peers moving onto secondary education before them. Still confused as to how Lynn justified revising the IQ score reflected by this data from 97 to 87/8, I asked Gill for more clarification on this question. This is his response:

When the debate "raged" there were arguments regarding the representativeness of the various samples being compared. I can truly say that ours was a NATIONAL sample (in the strict statistical meaning of the word).

This can absolutely NOT be said about the English samples our results were being compared to - usually "convenience urban samples", that is, nothwithstanding, non-sampling at school-level, that is, all classes and all pupils within classes being included (again - for convenience).

Jumping from 97 to 88 has to do with urban and rural data. Not unsurprisingly rural schoolchildren, in Ireland, in 1972/73, would be totally "out of tune" with IQ tests (particularly of the kind like Raven's Matrices). Their scores were lower than the urban children's. We argued that any attempt to compare British Isles samples should take this into account (nearly all Raven's data was from urban children).

So Gill and Byrt’s results show almost no difference between urban Irish and English students, and rural Irish students trailing somewhat, which Gill believed could partly be explained by unfamiliarity with testing – a similar problem identified by MacNamara.

Arriving at a figure

What do we find when we gather other data on Irish IQ? Psychologist Russell Warne collected as many samples of scholarly literature on the subject as he could find, producing a meta-analysis of data broken down by year and country (Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland or the United States) and visualised in the following scatter plot:

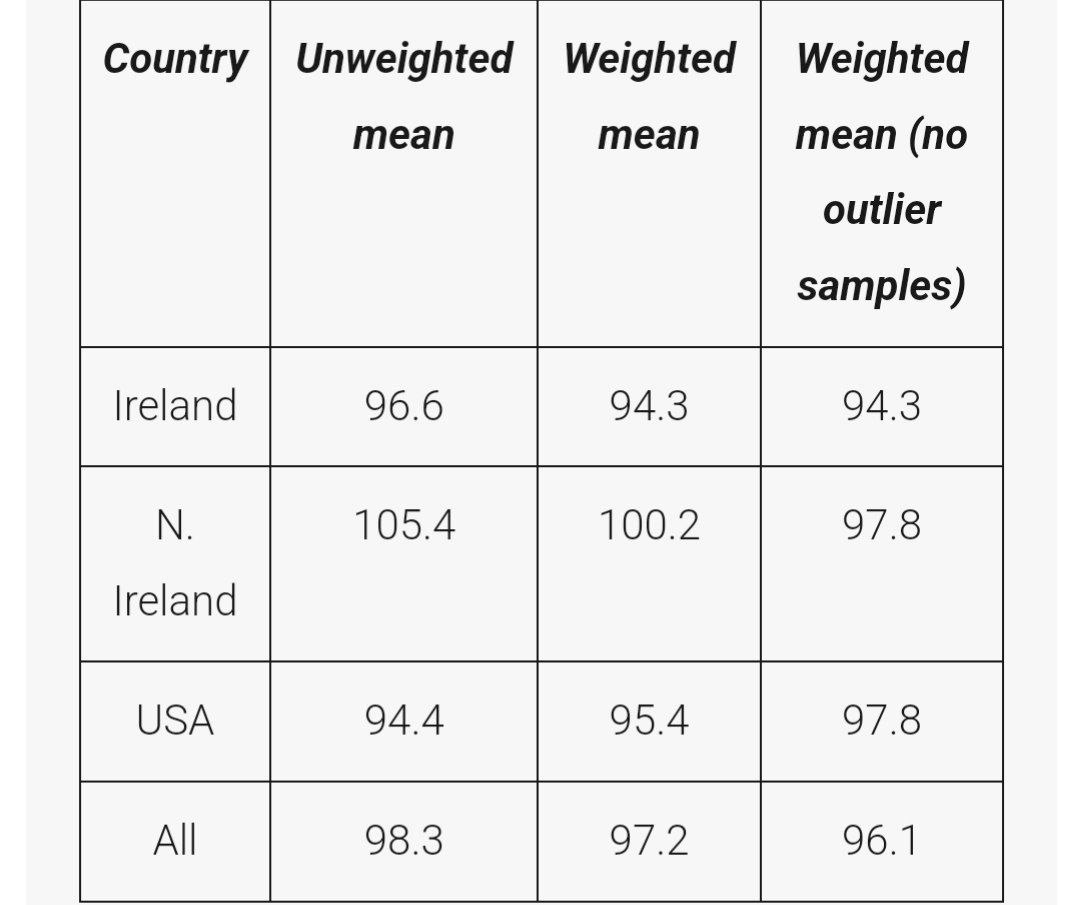

The extremely low scoring outliers conducted in America were on illiterate, foreign-born Irish draftees who scored 80.9 on an Army IQ test, and 25 low functioning foreign-born draftees, so both can be reasonably ignored for the purposes of calculating reliable averages. Warne comes up with these average scores, the most reliable of which are the weighted scores excluding extreme outliers:

Some of Warne’s data on Ireland was collected from Lynn, who adjusted for the Flynn effect to lower the Irish samples. Warne opts not to do this, which makes the data from the US and Northern Ireland substantively higher than the Irish result:

Without these four samples, [Lynn’s Flynn effect corrected samples] the weighted mean IQ for the Republic of Ireland is 97.5 and the weighted mean IQ for all remaining samples is 97.7.

Regardless of the methodological choices, it is clear that typical scores for ethnic Irish individuals are in the mid-90s.6

Recent developments

Though the evidence seems to point to Irish IQ trailing the rest of Western Europe slightly in the 20th Century, there is some evidence this gap has now disappeared. In his research, Lynn pointed to an achievement gap between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland’s education system – on the so-called “eleven-plus” exams administered to students in their last year of primary education. These standardised exams served as a useful measure of general intelligence, and Lynn noted that Protestants scored slightly higher than Catholics. When the standardised intelligence test was scrapped from the eleven plus, it was

replaced with tests in English, maths, science and technology, and these can be regarded as proxies for intelligence. The results of the 2008/09 test were that 26.7% of children in Protestant schools and 25.5% of children in Catholic schools obtained scores in grade 1 (the highest grade), and 36.0 % of children in Protestant schools and 35.5% of children in Catholic schools obtained scores in grades 1-3. Once again, the results (all supplied by the Northern Ireland Department of Education) show that Protestants performed slightly better than Catholics.7

Lynn’s reason for drawing on this data was to support his thesis that Catholicism had a dysgenic effect on the Irish, as the best and brightest were selected for celibacy, while openness, a trait associated with high intelligence, tended to be higher in Protestants. Since Catholicism has been a marker of the Irish ethnic identity in the Northern Irish state, it’s reasonable to infer something about Irish IQ from these results too. A 2015 report on education inequalities in Northern Ireland found that Catholics were now outperforming Protestant students, and that the gap between them was widening.

In terms of religion and educational attainment, the key finding was a persistent and overarching trend of higher proportions of Catholics achieving the education targets in all three areas (GCSEs, GCSEs including English and Maths, and A Levels), than both Protestants and ‘Others’. Furthermore, the gap between Catholics and Protestants widened between 2007/08 and 2011/12 for all three education targets….Therefore, this is a persistent, and increasing, inequality8

Similarly, in 2016, the Northern Irish government released data which revealed Catholics had outperformed Protestants in GCSE exams in every year of the new millennium. Of course, these exams are not as pure an intelligence test as the eleven plus Lynn cited, but it is worth noting that Catholics were outperforming Protestants despite a worse economic background:

However, young Catholics have achieved a higher proportion of top grades every year since 2000/01.

This is despite the fact that Catholic children are more likely to come from a deprived background.9

Turning to the South, one notable trend has been how high Irish students have scored on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) carried out by the OECD. This test is carried out on over 600,000 students, testing their abilities in reading and mathematics rather than anything that can be studied and memorised, so it is a good reflection of a country’s general intelligence. In 2011, Lynn and Gerhard Meisenberg translated PISA scores from 2000-2009 into IQ scores, concluding Ireland’s performance reflected a national IQ of 100.10

In the 2009 rankings, Ireland ranked 30th in mathematics, and 19th in reading. In the 2018 version, Ireland had climbed to 8th in the reading rankings, and 12th in mathematics. In the weighted rankings that year, the top 6 positions were all held by East Asian countries (Lynn concluded East Asian countries were the highest IQ in his research) followed by Estonia, Canada and Ireland. So excluding the East Asian countries like Hong Kong and Singapore, Ireland would be ranked third in these rankings.

In his later, 2015 paper on Catholicism and IQ, Lynn questioned if PISA was as good a test of IQ as many had assumed, given that more research backed up the lower Irish IQ, this time drawing on a study carried out in Galway on twins born in the 1980s which placed their IQ in the low 90s. It seems to me more reasonable to assume a slight increase in the decades since to put Ireland on par with or slightly ahead of the rest of Western Europe, especially now that Ireland ranks as one of the highest European countries. It may not be a perfect reflection of general intelligence, but it also seems unlikely a country at the low end of the Western world in IQ would consistently rank so high.

Conclusion

As we have seen, the original claim which popularised the topic of a low Irish IQ comparable to African-Americans was produced by Eysenck off an unreliable study. He later walked back his claim from a fifteen to a three point gap between England and Ireland, but focused on the difference between England’s highest IQ region and Ireland to make a six point gap the focus. This later data was drawn from Richard Lynn, who did more to study Irish IQ than anyone. Lynn, in his 2006 book Race Differences in Intelligence, concluded an IQ of 96 for the Irish, though he included his low interpretation of Gill and Byrt’s research, which they dispute.11 Russell Warne, in his meta-analysis of studies on Irish IQ concludes the same number of 96/97.

There seems little reason to doubt this number of is accurate for Ireland in the 1980s and 90s, and Lynn produced some interesting theories as to why Ireland trailed the rest of Europe slightly – chiefly its long history of mass emigration depriving it of more intelligent people. Recent performance by Irish students – outperforming Protestants in the North despite a wealth difference and scoring among the highest in the world on PISA rankings – suggests that the four point difference between Ireland and the rest of Europe has probably waned, and if the PISA scores were treated as a good reflection of intelligence, would put Ireland right at the top of the rankings. Though Ireland ranked below the European average, it was never a remarkable gap, certainly not large enough to mark Ireland out as a special case in Europe, and what gap there was likely no longer exists.

MacNamara, J. (1988). Race and Intelligence. The Irish Review (1986-), 3, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/29735312

MacNamara, J. (1964), Zero error and practice effects in Moray House English Quotients. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 34: 315-320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1964.tb00642.x

Lynn, R. (2015). Selective Intelligence, Roman Catholicism and the Decline of Intelligence in the Republic of Ireland. Mankind Quarterly, 55(3), 242.

https://www.unz.com/runz/raceiq-irish-iq-chinese-iq/

Byrt, E. & Gill, P. (1975). Eysenck and the Irish IQ: The evidence that proves him wrong. The Education Times

https://russellwarne.com/2022/12/17/irish-iq-the-massive-rise-that-never-happened/

Lynn, R. (2015). Selective Intelligence, Roman Catholicism and the Decline of Intelligence in the Republic of Ireland. Mankind Quarterly, 55(3), 242.

Burns, S., Leitch, R., & Hughes, J. (2015). Education Inequalities in Northern Ireland. Summary Report March.

https://www.irishnews.com/news/2016/10/08/news/catholic-pupils-do-better-in-gcses-every-year-since-millennium-725266/

Meisenberg, G., & Lynn, R. (2011). Intelligence: A measure of human capital in nations. Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies, 36(4), 421-454.

https://www.irishtimes.com/news/irish-placed-low-on-academic-s-iq-table-1.1289495

Richard Lynn, as Keith is almost certainly aware but cannot say above lest he not be taken as seriously, was hired to be an advisor to a state funded think tank in the 26 counties in which role he argued that Ireland should embrace the compulsory sterilization of its people on the road to modernity and economic development etc. The proposal was rejected and he ended up in the North where he founded the “Ulster Centre for Social Research,” where he would write stuff like this talking about Irish people having the IQ of American blacks etc.

The long and the short of it is that the lrish as low IQ is frankly just another chapter in Anglo Irish ethnic conflict and nothing more than that. It is in such a context that I would argue that the origins of the Irish as low IQ do not begin with some obscure German academic but with The Times of London depicting us as apes in the 1840s and we all know what was happening then.

I don't know about low IQ, but the Irish have proved to be very cowardly in the last few years. I hate saying that because I am Irish, but I think we have been an absolute DISGRACE to our antecedents.