The left in Britain, as in the rest of Europe, has been keen to present a narrative of Britain as a historically multicultural country. At the same time, the Dissident Right , in its focus on the radical changes affecting Europe after the Second World War sometimes miss just how recent the radical demographic changes of European nations are. The 1980’s and 90’s, the decades of neoliberalism and rapid globalisation are also when we begin to witness the rapid transition to replacement migration policies in historically White nations. Perhaps nowhere is this more stark than the UK under New Labour, which serves as an interesting case study in this regard.

The leftist myth around immigration to Britain is that it was a historically multicultural region which opened its doors more fully to non-White immigration after the Second World War. Leftists even talk of non-White immigrants rebuilding Britain after the Second World War, thus giving them a permanent stake in the country. This is usually in reference to events in 1948, when 1027 passengers were carried from Jamaica to London on the HMS Windrush, a voyage that has become symbolic of Britain’s transformation to a multicultural country. There is often a sense that after this Britain embraced multiculturalism and entered an inexorable path to its current state, but this is quite far from the truth.

Firstly, the arrival of the Windrush was actually neither expected or welcome by the British government. Minister of Labour George Isaacs assured parliament that others would not be encouraged to follow. 11 Labour MP’s signed a letter directed to PM Clement Attlee dissenting against immigration policy and expressing fears that Britain would host a larger influx of immigrants:

“This country may become an open reception centre for immigrants not selected in respect to health, education, training, character, customs and above all, whether assimilation is possible or not.

The British people fortunately enjoy a profound unity without uniformity in their way of life, and are blest by the absence of a colour racial problem. An influx of coloured people domiciled here is likely to impair the harmony, strength and cohesion of our public and social life and to cause discord and unhappiness among all concerned.

In our opinion colonial governments are responsible for the welfare of their peoples and Britain is giving these governments great financial assistance to enable them to solve their population problems. We venture to suggest that the British Government should, like foreign countries, the dominions and even some of the colonies, by legislation if necessary, control immigration in the political, social, economic and fiscal interests of our people.

In our opinion such legislation or administrative action would be almost universally approved by our people.”

Letter to the Prime Minister, 22 June, 1948.

In Prime Minister Attlee’s response, he assured the MP’s that their fears were misplaced:

I note what you say, but I think it would be a great mistake to take the emigration of this Jamaican party to the United Kingdom too seriously.

…

It is difficult to prophesy whether events will repeat themselves, but I think it will be shown that too much importance – too much publicity too – has been attached to the present argosy of Jamaicans. Exceptionally favourable shipping terms were available to them, and there was a large proportion of them who had money in their pockets from ex-service gratuities. These circumstances are not likely to be repeated; yet even so not all the passages available were taken up.

It is too early yet to assess the impression made upon these immigrants as to their prospects in Great Britain and consequently the degree to which their experience may attract others to follow their example. Although it has been possible to find employment for quite a number of them, they may well find it very difficult to make adequate remittance to their dependants in Jamaica as well as maintaining themselves over here. On the whole, therefore, I doubt whether there is likely to be a similar large influx.

So not only did many in Labour object to any entry of these foreigners to Britain, but even the government officials overseeing it promised this would not facilitate larger entry. It is hard to imagine any of these men supporting the kind of transformative replacement migration that has come under New Labour and modern Conservative party. In the letter, Attlee refers to the entry of just 492 Jamaican immigrants as a “large influx”, 1.2 million people immigrated to the UK in 2022.

Immigration Restriction in the Post-War Period

In a British government meeting in 1955, proposals were debated for the creation of “an independent committee of enquiry into coloured migration”, noting that “the first purpose of an enquiry should be to ensure that the public ... were made aware of the nature and extent of the problem: until this was more widely appreciated the need for restrictive legislation would not be recognised”.

In 1962, the public had indeed grown more hostile to the problem, and the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan passed the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, which, for the first time, legally curtailed free movement for citizens of Commonwealth countries. Everyone born outside with UK or without a UK passport was now subject to stricter immigration controls. Up to this time, there was an ambiguity in British law that allowed any citizen of a commonwealth country to immigrate to Britain. By this time, the government favoured the entry of Irish and other White immigrants to the UK, but wished to restrict the entry of others. The result was a voucher system which was seen as discriminating on the basis of race. Home Secretary Richard A. Butler said of the act:

The great merit of this scheme is that it can be presented as making no distinction on grounds of race or colour, although in practice all would-be immigrants from the old Commonwealth countries would almost certainly be able to obtain authority to enter … We must recognise that, although the scheme purports to relate solely to employment and to be non-discriminatory, its aim is primarily social and its restrictive effect is intended to and would, in fact, operate on coloured people almost exclusively.”

Labour initially opposed this kind of immigration restriction, but in 1964 elections opponents of immigration restriction were punished by the electorate.

In 1968, fearing a public backlash a Labour government further restricted immigration with the Commonwealth Immigrants Act. The 1962 act had left a loophole for so-called “Asian Africans”, who were now being forced out of countries like Kenya, which were pursuing an ‘Africanisation’ policy. Labour rushed through this bill to restrict the entry of these people to Britain. Here again, we can find a nativist motive among the politicians in question. Cabinet secretary Sir Burke Trend defended the policy in a memo, on the basis that:

“a reasonable case could be put… that the Asian community in East Africa are not nationals of this country in any racial sense”.

Under this act, a citizen of the Commonwealth could only live in the UK if they, or at least one of their parents or grandparents, had been born, adopted, registered or naturalised in the UK, thus excluding almost all the “Asian Africans”.

When the Conservatives came back to power in 1970, immigration was further tightened by the Immigration Act of 1971, which gave the government complete control over the immigration of “non-patrials” - people without close connections to the United Kingdom through birth or descent. The act also replaced “work vouchers” with temporary work permits. Representatives of Commonwealth countries lambasted the bill, with the prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago accusing the British government of “open unadulterated and unambiguous racialisms”.

A Conservative government again restricted immigration in 1981 when they passed the British Nationality Act, which further restricted the definition of British citizenship to include only those with close ties to the United Kingdom.

Opening the Floodgates

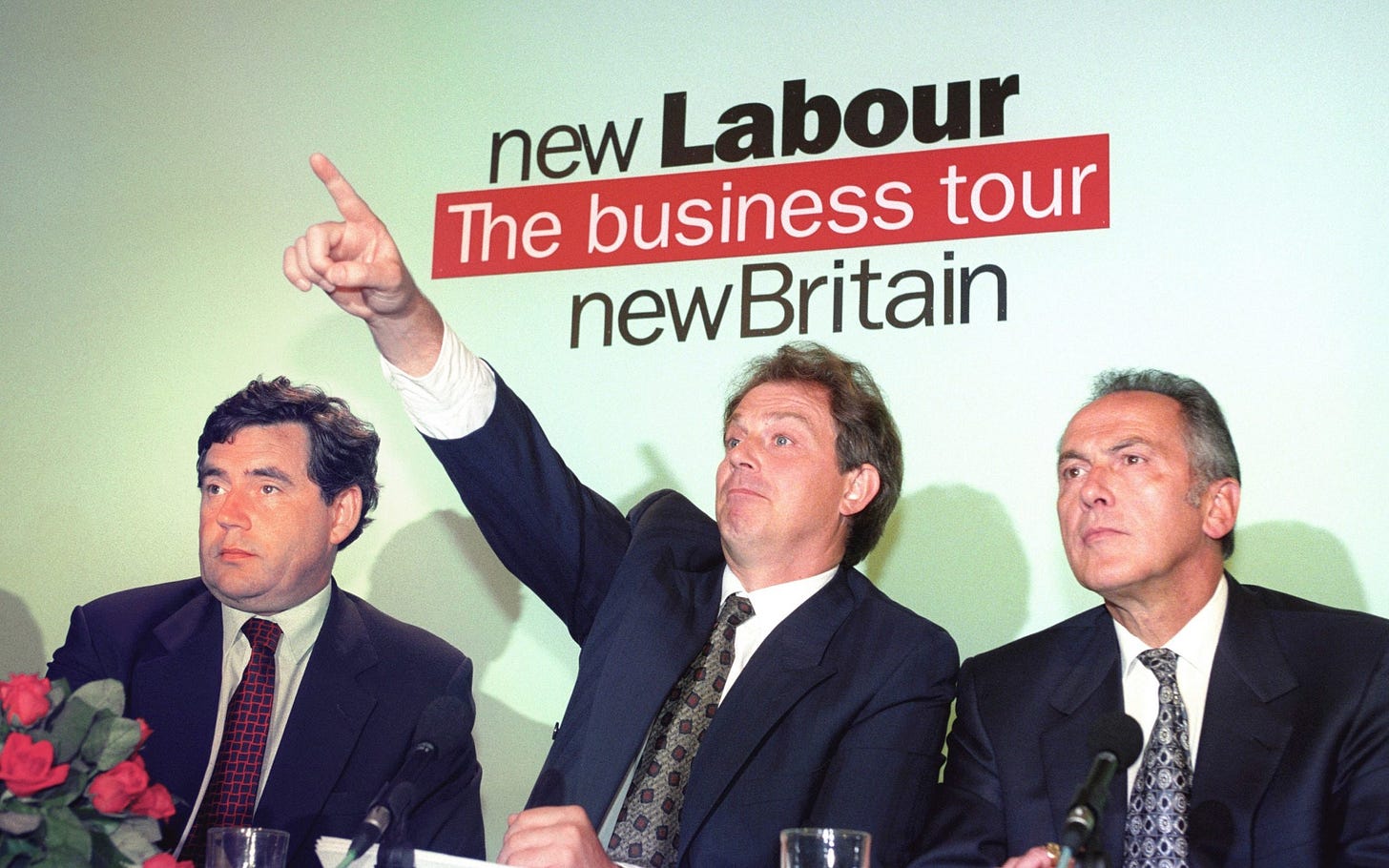

Without question, the majority of blame for the UK’s rapid demographic transformation rests at the feet of New Labour. As late as 1991, the UK was still 95% White. When New Labour took government in 1997, net migration to the UK was typically about 50,000 per year, a figure Labour and Conservatives had tacitly agreed to. By Labour’s second term from 2005-2010, this had quintupled to 250,000 per year. By the time they left office, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown’s Labour had added 2.7 million new arrivals to the UK workforce.

What explains this rapid transformation? Here I want to draw on a book called Labour’s Immigration Policy: The Making of the Migration State1 which aims to explain exactly that.

Left-wing parties supporting mass immigration is often explained as a cynical effort to gain new voters, as immigrants tend to vote for parties which have a positive attitude to immigration, but there was no electoral logic to New Labour’s policy:

The Labour government’s liberalisation of immigration policy went against public opinion, and therefore there was no obvious electoral dividend to their expansive regime. Whilst the British public has long been in favour of reducing immigration, the high level of public concern began in 2000, at a time where the New Labour government were pursuing the most expansive immigration regime to date.

Indeed, public concern about immigration contributed to New Labour’s eventual ousting in the 2010 election, and scuppered their chances of a return to office in 2015.2 We might expect a transformation this rapid to be the result of sustained lobbying, perhaps by left-wing NGO’s or big business.

The NGO sector had very little impact on these immigration policies, as they were instead focused on the rights of resident migrants and family reunification. As for big business, while there was general support for the expansive immigration policy of New Labour, this did not lead to a sustained lobbying effort to cause these policies. On this, a quote by Labour MP David Blunkett is instructive:

I think they [employers] helped. They helped clarify in our own minds what we believed was right, namely that there were jobs that needed to be filled, there were skills that we were short of, there was economic growth that would be curtailed, there was inflation that would accelerate if we didn’t do it.

The aims of big business were in line with New Labour, but the initiative for this transformation still came from within the party. Thus, Consterdine argues that the key to understanding the transformation of Britain into a migration state is the orientation, specifically economic, of Labour in the 1990s. The policy transformation was rooted in three contingent elements of Labour’s new philosophy:

The Party’s neoliberal economic programme, including counter-inflationary measures and labour market flexibility, and underpinning this programme, the Party’s diagnosis of the global political economy. This economistic reasoning was reinforced by Labour’s culturally cosmopolitan notion of citizenship and integration. Coupled with Labour’s historical values of openness and tolerance, an expansive immigration policy ‘made political sense’

New Labour’s Embrace of The Third Way

Under Tony Blair’s vision, Labour abandoned many of its old socialist trappings and embraced a neoliberal “third way”, adopting many of the economic policies of Margaret Thatcher - Labour politician Peter Mandelson famously declared, “we’re all Thatcherites now”.

Blair’s young, rejuvenated Labour was focused on modernisation in all its forms. This included denouncing the Keynesian demand management approach to economics Labour had traditionally taken, which was heavy on state intervention. Blair recognised that the new reality was a fluid global marketplace which needed to be harnessed rather than restricted.

The central idea of the third way was a restriction of traditional state intervention and working to resolve problems of capitalism with market solutions. Labour had been punished by the electorate and left for years in the wilderness due to its perceived economic mismanagement, corrected by the monetarist policies of Thatcher. New Labour adopted the Thatcherite focus on counter-inflationary measures as central to good economic governance. When it came to the labour market, this meant an intense focus on “flexibility”. New Labour adopted the monetarist belief that supply increases demand, and thus extra competition in the labour market would reduce inflationary pressures.

Labour market flexibility was at the heart of Blair’s vision of the competition state and represents the bedrock of Labour’s economic policy both independently and in terms of its effect on keeping inflation down

A special advisor to the government is quoted as tying Labour’s embrace of neoliberalism and abandonment of Keynesian economic policy directly to its radical new immigration policy:

The main thing is that the reorientation on economic policy of the centre left—away from Keynesian demand management towards a more explicit embrace of globalisation—lent itself more firmly towards embracing immigration too. The emphasis on skills and education and openness to global markets meant that you had people more open to arguments about migration being an important component of a successful economy.

With a new outlook that emphasised openness, competitiveness, flexibility and modernisation, it only made sense that Labour would adopt an expansive immigration policy. Immigration restriction was one of those old holdovers, like industrial strikes or demand management, which were misguided attempts to lift up the lot of working Britons through excessive state control over the economy.

Of course, it would be a mistake to imagine that Labour were pursuing some kind of ineluctable logic of capital and that their own ideals were not a factor. As representatives of the British Left, Labour politicians had always had more cosmopolitan attitudes to immigration. Even in the 1964 elections mentioned above, many mistakenly ran on criticising Conservative immigration restriction policy as racist. If immigration being opened up would benefit Labour’s new embrace of neoliberalism, this was an added benefit to the party members who had long hoped for a more open and diverse country.

With values of openness and tolerance inscribed at the heart of the Party, Labour’s approach to integration complemented the notion of having an expanding immigrant population. The Party embraced diversity and their integration policy was grounded in multicultural ideas. This was also reflected in their concept of British national identity, based on ‘shared values not unchanging institutions’. Blair’s notion of British identity was founded on ideas of liberal pluralism, communities, inclusivity, openness, tolerance and rights with responsibilities.

This post-national vision was evidently common among senior Labour policy makers by the 1990s. Indeed, one advisor to the Blair government has since come out and admitted that the transformation of Britain into a multicultural country was motivated by a desire to “rub the Right’s nose in diversity”.

Essentially, liberal pluralists like Blair, who did not believe in the traditional conception of the nation-state, used the surge in globalisation and economic modernisation to attach their values of openness and pluralism to an embrace of economic globalisation. It was the final synthesis of Labour’s left-wing social values and the Conservatives economic liberalism that facilitated the rapid transformation of Britain into a migration state.

The alignment of economic liberalism with national-cultural progressivism also helps to explain why previous governments, in particular the Conservative administrations of the 1980s and 1990s, had not previously liberalised immigration policy, for New Labour’s economic liberalism was certainly not new.

This is a familiar tale, not just in Britain, but across the West. If Labour embraced the economics of Thatcher in their third way synthesis, subsequent Tory governments embraced the social values of Labour in turn.

David Cameron's government supported the introduction of gay marriage, while net migration has continued to reach record rates under successive Conservative governments. In other Western states, left-wing parties who previously opposed mass-immigration on the basis of labour concerns have embraced open borders policies as part of their larger philosophy of pluralism and openness. The third way synthesis of Blair and Clinton has become the dominant approach to politics of establishment parties, left and right, in the neoliberal West. That this new political synthesis has coincided with an unprecedented acceleration of immigration into majority-White nations is not happenstance.

Consterdine, E. (2017). Labour's Immigration Policy: the making of the migration state. Springer.

Beckett, M. (2016). Labour Party: Learning the Lessons from Defeat Taskforce Report. London: Labour Party.

You're very good at collating ideas that are basically taken as read in our circles, and then boiling them down into a cohesive, easily accessible format (e.g. the slavery thread). Thanks for doing it again, you'll do more with this one essay than most would with 1000 Twitter sperg-rages.

Do Canada next Keith. It's even worse than the UK.