What political system governs the modern West? Despite there being more polarisation than ever across the political spectrum, the actual policies of mainstream left and right-wing parties are more similar than at any other time in the post-war period. Even in radical circles, containing people sharing the same niche worldview and well-versed in political theory, you will still find significant divergence over whether the system they are combating is a technocratic form of socialism, neoliberalism, communism, or the second coming of fascism. Obviously, the ideologies that once clearly defined political camps no longer align neatly with the consensus that now dominates Western democracies.

I want to argue that the main reason this debate is so muddled is that the ideological poles of the 20th century — liberalism on the right and social democracy on the left — have largely merged since the 1990s. What dominates Western politics today is a hybrid: a broad social liberal consensus that doesn’t neatly fit either tradition, but could equally be argued to be their natural end point. Almost all major political currents in the West operate within this merged framework, which makes it harder to name or oppose the system as something coherent and distinct.

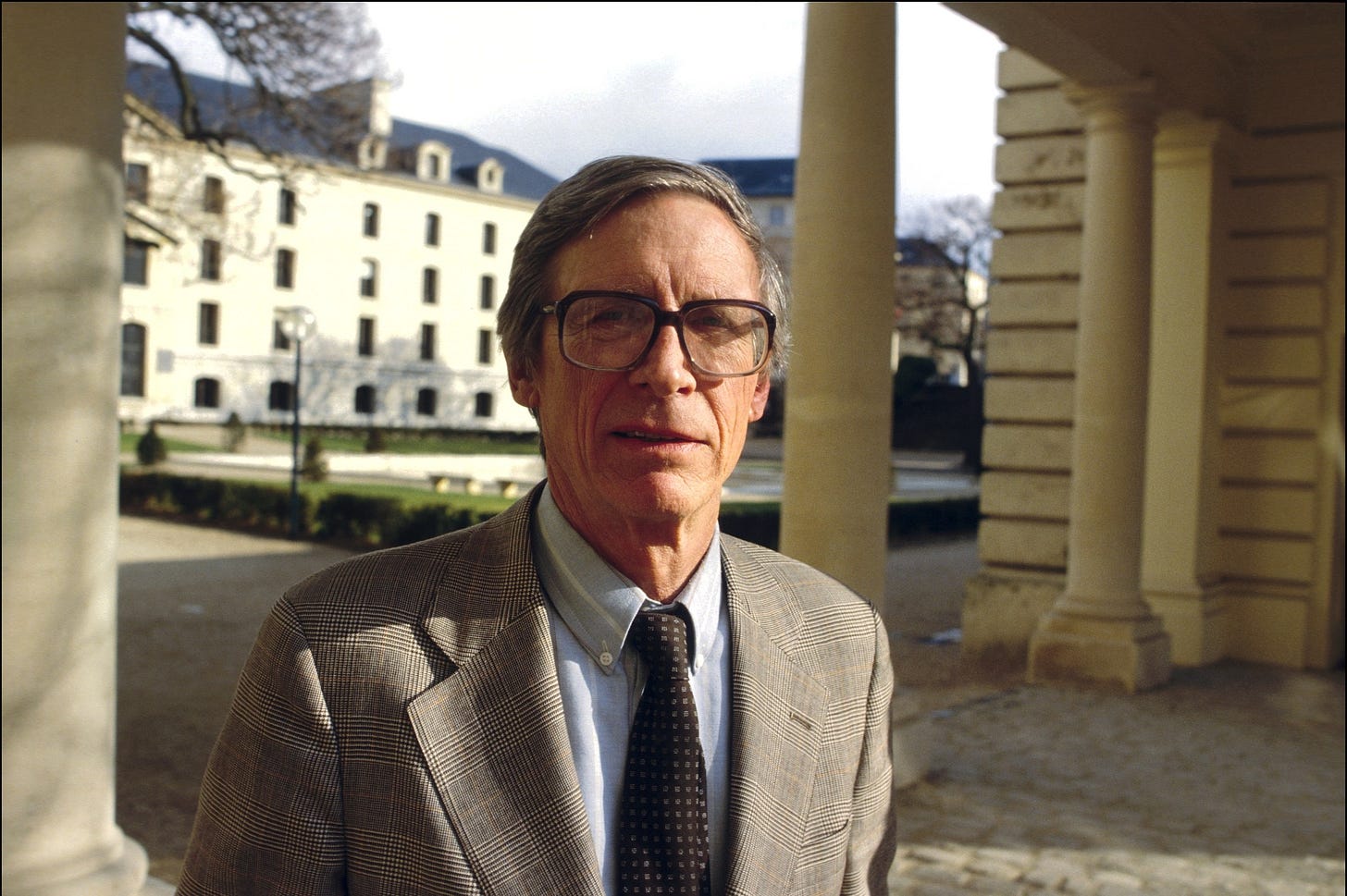

One problem on the right is that we often look in the wrong places to understand the origin of the modern system. Though radicals like the Frankfurt School, and French “postmodern neo-Marxists” had great influence on the New Left, they did not foresee the kind of dynamic, market-based economic system leftist politicians would end up embracing today. One thinker who has had a great, direct influence on some of the most powerful politicians of today is the British sociologist Anthony Giddens. Giddens is a prolific author and highly influential academic, who served as Director of the London School of Economics from 1996 until 2003. His introduction to Sociology has sold over a million copies, and he is notable for being the rare academic to reach a large audience outside academia.

Bill Clinton’s reform of the Democrat Party was influenced by Giddens, but he is better known for being the chief intellectual influence on Tony Blair and the creation of New Labour. In two books, ‘Beyond Left and Right’ and ‘The Third Way’, Giddens charted a path to renewal for social democracy, a new model of left-liberal governance that would be dynamic, make use of markets, and be less attached to the bloated welfare state that social democrats had previously prided themselves on. It was just what politicians like Blair and Clinton needed to rehabilitate parties that had gained negative reputations for socialist mismanagement, real or perceived.

Reading these works now is interesting, because Giddens was highly prescient in seeing how the welfare state in the West would develop, not least because the suggestions he produced directly influenced so many of the people who have been in charge of it since. Blair and Clinton did not just rejuvenate the social-democratic parties in their own countries, but produced a pragmatic model that other establishment left parties would imitate for electoral success. But they did not just change the left. By embracing many of the changes brought about by neoliberalism, they created a new social liberal centre which establishment parties, left and right, have gradually adopted to the point of near absolute consensus across the West.

In order to demonstrate this great progressive synthesis, it’s helpful to look back at how Giddens defined the old left and the neoliberal right in his book The Third Way, published in 1998. Here are the structural features Giddens attributes to these worldviews:

Classical social democracy (the old left)

Pervasive state involvement in social and economic life: The state actively directs economic planning and social programs to ensure stability and equity, advocates nationalising important industries and utilities.

State dominates civil society: Government authority overshadows independent organisations, state-led solutions trusted over private initiatives.

Collectivism: Emphasises group welfare and solidarity, leans into class-based politics and promotes shared economic goals over individual interests.

Keynesian demand management, plus corporatism: Uses government stimulus to boost demand and collaborates with unions and businesses to stabilise wages and production.

Confined role for markets: Social economy; markets directed by the state, private enterprise and state ownership blended to pursue social goals.

Full employment: Aims for universal job availability through state intervention, viewing unemployment as a policy failure.

Strong egalitarianism: Sees inequality as a problem to be addressed. Seeks to minimise income and wealth disparities through progressive taxation and redistribution policies.

Comprehensive welfare state: ‘cradle to grave’ benefits; state directly provides universal services like healthcare, education, and pensions. Welfare benefits are universal.

Linear modernisation: Pursues steady industrial growth and economic progress, assuming continuous growth and technological advancement.

Low ecological consciousness: Prioritises economic and social goals over environmental concerns, with minimal focus on sustainability.

Internationalism: Promotes a sense of global solidarity, often through socialist or labour movements, to foster cooperation across nations; may oppose immigration for social reasons but hostile to xenophobia and nativism.

Belongs to bipolar world: Operated in a Cold War context, aligning either with Western social democracy states or more hard-left socialist blocs in global politics.

Examples: Clement Attlee, Willy Brandt, George Galloway

Theory: The Great Transformation by Karl Polanyi, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money by John Maynard Keynes

Neoliberalism (Thatcherism, the new right)

Minimal government: Reduces state interference in economic and social life, favouring deregulation and privatisation to enhance efficiency.

Autonomous civil society: Encourages private organisations and entrepreneurship; seeks to limit state control over community and individuals.

Market fundamentalism: Views unregulated markets as the primary driver of prosperity, prioritising competition and free enterprise. Supply-side economics — allowing for an abundance of supply/entrepreneurialism will create its own demand.

Individualism: Combines traditional social values with a focus on personal responsibility and entrepreneurial freedom.

Free labour market: Treats labour as a commodity, with wages and employment determined by supply and demand; opposes union influence as coercive and driver of inefficiency.

Acceptance of inequality: Views economic disparities as natural outcomes of market competition, with minimal state intervention to redistribute wealth.

Civic nationalism: Leans into patriotism, skeptical of supranational institutions (Euroscetpicism of Farage/Thatcher)

Welfare state as safety net: Limits welfare to minimal support for the neediest, emphasises “safety net” over universal entitlements.

Linear modernisation: Assumes continuous economic growth through market-driven innovation, with little regard for social or environmental limits.

Low ecological consciousness: Prioritises economic growth over environmental protection; distrustful of green policies as statist and bureaucratic power-grab.

Realist theory of international order: Pragmatic approach to global relations; focuses on national interests and power dynamics over ideological alliances.

Belongs to bipolar world: Operates in a Cold War framework, aligning with Western capitalist interests against socialist blocs.

Examples: Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, William F. Buckley, Javier Milei

Theory: The Road to Serfdom by Friedrich Hayek, Capitalism and Freedom by Milton Friedman

In this work, Giddens also outlines the features of his proposed Third Way. While Giddens’ description of the previous two models is helpful, his description of the Third Way is polemical and unhelpful, sounding more like election sloganeering than a serious analysis, like describing one feature as “no rights without responsibilities”. Now that we have experienced almost three decades of the new social democratic model Giddens proposed. I will outline a description of the new social liberal consensus that has emerged using similar categories to Giddens:

Social Liberalism (Modern Social Democracy, contemporary Centre-Left/Right consensus)

New mixed economy: synergy between public and private sectors; state used to boost “competitiveness” and stabilise market excesses with targeted interventions rather than state-planning; dynamism and efficiency of market economy directed for mass-affluence

Partnership with civil society; lack of sharp dividing lines between state, private sector and civil society, blending into one “regime”; NGOs fulfill social care roles and engage in social engineering; public-private collaborations on service provision

Pragmatic collectivism: encourages individual aspiration and entrepreneurship; social cohesion via “solidarity” and humanitarianism, rather than class-based politics or national consciousness

Social market economy: embraces globalisation and neoliberal market expansion, mostly focuses on supply-side policies (education, innovation etc.) to drive growth with little demand management or tariffs. Fundamental logic of market efficiency is embraced, but regulated for common good. “Stakeholder capitalism”

Flexible labour market: prioritises job creation and employability through training and education; little reliance on state to create jobs directly; rather supports "flexicurity" — facilitating flexible private labour markets while maintaining strong safety nets.

Moderate egalitarianism: prioritises equality of opportunity, maintains wealth redistribution via progressive taxation social programs for poor, but allows for growth of super-rich and accepts wealth inequality as unproblematic in itself

Cosmopolitan pluralism: cultural pluralism and multiracialism, mass-immigration to ensure labour flexibility and market competitiveness; civic patriotism but harsh suppression of ethnic/racial nativism

Targeted welfare state: abandonment of universal benefits-based welfare state; means-tested benefits and subsidies; focuses on returning welfare recipients to private sector

Non-linear modernisation: embraces technological progress and digital transformation; embraces complexity and disruption in economic and social change. Uses a pragmatic state to easily reshuffle human capital.

Ecological consciousness: “sustainable growth” and climate action; shift to renewable energy; carbon reduction; role of private sector in innovating solutions.

Globalised internationalism: multilateralism; peace through interconnectedness via global trade; cooperation on global issues via institutions like the UN, WTO, WHO; lifting up of the rest of the world via human rights universalism, developmental aid and trade.

Belongs to multipolar world: operates in an already globalised, interconnected world with multiple power centers; powerful actors from private and public sector collaborate to navigate tensions between global integration and national sovereignty.

Examples: Tony Blair, Bill Clinton, David Cameron, Emmanuel Macron, most establishment political parties today

Theory: A Theory of Justice by John Rawls, The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy by Anthony Giddens

Given that this consensus has veered to an embrace of market economics and globalisation more than its early advocates may have foreseen, and this consensus now represents a much larger progressive centre than merely the political left, I think a more apt term for this new consensus is social liberalism, merging social democracy of the left with the economic individualism and market-orientation of the right. Thus, it brings together the more individualist, market friendly trend of the left in the late 20th Century with the libertine, economistic trend of the right as it abandoned social conservatism and nationalism.

Justice as Fairness: The Intellectual Defence of Social Liberalism

Social liberalism has always been a trend in the liberal tradition, a variant that focuses on the active expansion of civil and political rights, as well as more material questions of social justice based on liberal humanitarian principles. It found its greatest advocate in John Rawls, one of the most influential social theorists of the 20th Century. Rawls’s theory of “justice as fairness” argues that a properly just liberalism would demand a limitation of inequality and a collective provision of goods for the least advantaged.

Arguing that the proper way to engineer society was behind an imagined “veil of ignorance”, liberals should create the kind of society an individual would want if they did not know where — into what class, race, gender, etc. — they would be born. Extreme poverty, lack of education or access to healthcare could prevent those with the misfortune of being born into impoverishment from exercising their freedom. This lays the foundation for a liberal defence of social democracy: maximal freedom for all necessitates an interventionist state to ensure liberty is not obstructed by material inequalities:

Significant political and economic inequalities are often associated with inequalities of social status that encourage those of lower status to be viewed both by themselves and by others as inferior. This may arouse widespread attitudes of deference and servility, on one side, and a will to dominate and arrogance on the other. These effects of social and economic inequalities can be serious evils and the attitudes they engender great vices... Fixed status ascribed by birth, or by gender or race, is particularly odious.1

Like Giddens, Rawls rejects both laissez-faire capitalism — for generating inequalities incompatible with maximising liberty — and the traditional welfare state, for placing too much control of the economy in the hands of a few planners.2 Rawls favours a “property-owning democracy” or “liberal socialism”. The difference between this and the welfare state capitalism of social democracy is that while the latter creates near-monopolies of the means of production and makes the individual reliant on welfare handouts from the state,

Property-owning democracy avoids this, not by the redistribution of income to those with less at the end of each period, so to speak, but rather by ensuring the widespread ownership of productive assets and human capital (that is, education and trained skills) at the beginning of each period, all this against a background of fair equality of opportunity. The intent is not simply to assist those who lose out through accident or misfortune (although that must be done), but rather to put all citizens in a position to manage their own affairs on a footing of a suitable degree of social and economic equality.3

This helps clear up some of the confusion about whether the modern system is properly socialist or liberal. While the technocratic, redistributionary state may seem at odds with classical liberal principles, theorists like Rawls have long since reconstituted liberalism to account for liberty as something that requires a material basis, which is best preserved by a state capable of remedying inequalities and illiberal outcomes produced by markets. And, while men like Giddens and Blair favour the social democracy model, their moral justifications are the same as Rawls, viewing liberal pluralism as the only just foundation for legitimate governance.

The Triumph of Social Liberalism

Every Western government today has converged on the social liberal model of democracy outlined by Giddens. In Europe, this is the politics of most establishment centre-left and centre-right parties, usually with a minority of an old social democratic left, and in some countries a populist right which may combine elements of any of the three. A couple of examples here are illustrative.

In Ireland, political parties have traditionally been hard to categorise ideologically. Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, the two largest parties traditionally, were divided by a Civil War rather than any clear split on ideology. By the early 2000s, Fine Gael were seen as aligning more with the Christian Conservatism of the continent, while Fianna Fail was seen as a true liberal, centrist party. The Labour party was seen as representing the traditional left, with Sinn Féin seen as a more ideologically flexible, populist force.

Now though, all parties have converged on support for the modern social liberal model. Fianna Fail and Fine Gael represent a large progressive centre, which align fully with modern social liberalism, and have together ushered in a great deal of radical social change to Ireland, as well as opening the country to a massive demographic change through mass-immigration. Both the Labour Party and Sinn Féin, as well as other smaller leftist parties, support a classical social democratic model, with each touting the Nordic model of socialism with universal benefits and more progressive taxation as a superior alternative to Ireland’s system.

As these parties come closer to government though, the tendency is for them to adapt to the social liberal consensus. When Labour have entered coalition governments, they have had to prioritise policies like protecting the minimum wage and minimising cuts to social spending, rather than any radical reform of the welfare state. Sinn Féin too, while remaining locked out of government, has yet moderated its old left positions to be seen as feasible managers of a modern, globalised economy, including abandoning a promise to raise Ireland’s notably low corporation tax. As I have written about before, politics in Ireland is not so much divided on a left/right axis, as it is split between a large progressive centre committed to a modern social liberal model, and a sizeable minority to their left that favour a classic social democratic model, but have gradually embraced more and more of its modern update.

In the UK, Tony Blair dragged Labour away from its old left baggage to an embrace of social liberalism. David Cameron, in turn, shifted the Tory party away from neoliberalism and toward Blairite politics. Cameron passed gay marriage, abandoned any commitment to social conservatism, and brought a new commitment to environmentalism. Cameron’s Tories also supported a “Big Society” initiative, which sought to use markets for paternalistic ends and combine civic organisations and charities to provide public services at a local level, in line with the modern social liberal model of government using civil society partnerships for welfare. When the Labour Party experimented with a return to the old left under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, they suffered a crushing electoral defeat, before Keir Starmer returned them to a modern social liberal ethos.

Why Social Liberalism Won

In opposition, leftist parties still advocate a classic social democratic model that often looks back nostalgically on the golden age of social democracy in post-war Europe. But in government, all parties converge on the social liberal model of modern social democracy. Ideological leftists may blame this on capture of leftist politics by big business interests, pressure from neoliberal media, or corruption inherent in parliamentary politics, but these parties are generally true believers in the ideals of the old left. The pressure to adapt to the social liberal model needs to be understood as a reflection of structural realities created by changes in the economic system brought about by the acceleration of globalisation since the 1970s.

Firstly, trade liberalisation, the mobility of global capital, and the growth of multinational industries has eroded the classical model of social democracy’s reliance on national industry and more confined markets, which could be micromanaged by state planners. Maintaining national industry, full employment, and high wages creates inefficient industries incapable of competing on a global stage, which led to cases like the decline of traditional British industries like steel during the rise of globalisation.

Second, the shift to service economies, gig work, and the rise of the “precariat” in place of the traditional working class and trade unions, has weakened the traditional collectivist base of the left and made goals like full employment and wage guarantees unrealistic and unwanted. Focus on these goals over “competitiveness” and supply side innovations would mean stagnation in a modern liberalised service economy, forcing leftist parties to pursue growth by increasing market efficiency. Rapid technological growth and fluid capital shifts make social democracies’ demand of job guarantees and the protection of living standards for workers in entire industries impossible, with the only way to secure affluence for workers now seen as making them capable of adaptation through education and training, thereby encouraging economic individualism.

Third, with the unprecedented growth of the post-war period now gone, with aging populations, skyrocketing national debt, and global tax competition and capital flight eroding the traditional corporate tax base, the comprehensive and universal welfare systems, made for the young, working population of the post-war period, is increasingly unsustainable. With little long-term industrial planning or investment after the neoliberal experiment, Western governments can do little to provide the growth necessary to fund existing social programs than by attracting market confidence and global investment, which requires moderating government spending and maintaining a pro-business environment.

Fourth, the move to green economics is in direct conflict with the old left’s reliance on traditional heavy industries like coal and steel to deliver jobs and economic growth. The international consensus on environmental sustainability encourages public-private partnerships, market innovations and a shift to a tech-driven service economy to reach carbon reduction targets, policies which have evolved with the new social liberal model.

Finally, the traditional White working-class base of the social democratic left has been undermined by demographic, as well as economic change. The post-war socialism of Europe owed a lot to the spirit of national unity and collective sacrifice that emerged during the war. The British electorate threw out the old Tory Winston Churchill in favour of the socialist Labour Party, which led to the establishment of the NHS, among other great socialist institutions. The concept of ‘folkhemmet’ or ‘people’s home’ was the foundation of the Swedish welfare state constructed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party. Sociological research has established that declining ethnic homogeneity leads to a decline in social trust as well as decline in support for welfare state policies. A study by Harvard economists which looked at the reasons for why the United States did not follow its Western counterparts in establishing a comprehensive social democratic model attributed about half the difference to America’s racial and ethnic heterogeneity. They note that:

Support for welfare is lower among people who live near welfare recipients of a different race. The difference between within-race and across-race effects seems to mean that people have a negative, hostile reaction when they see welfare recipients of a different race, and a sympathetic reaction when they see welfare recipients of their own race.4

As Europeans moved further in time from the spirit of 1945, towards greater individualism, and witnessed their societies become more diverse through mass-immigration policies, support for the socialism of old has declined.

One can demonstrate some of these structural pressures by imagining a scenario where Jeremy Corbyn had become Prime Minister and attempted a return to classical British social democracy, including his planned abandonment of austerity and increase in the corporate tax rate. Britain would likely have faced a flight of foreign investment, and a potential stock market crash which would have forced the social democratic government to enact even harsher austerity. A lack of market confidence in old left policies would have created bond market turmoil, resulting in higher government bond yields and increased borrowing costs, a major obstacle to the kind of Keynesian deficit-spending the old left used to stimulate economic growth.

Regardless of their adherence to the ideals of the old left and and the success of the post-war welfare state, leftists are forced by the realities of an already globalised capitalist system to adopt the less statist, more market-friendly adaptations of social liberalism. Labour’s director of communication Peter Mandelson once declared “we are all Thatcherites now”, while Thatcher’s Tory successor David Cameron titled himself the “heir to Blair”. Both these statements reflect a reality where the old left and new right have both had to to the dominant social liberal centre to maintain electability and economic stability, with either pure neoliberalism or an old social democratic model proving unfit for modern economic and political realities.

For neoliberals, those political realities came from the deep unpopularity of neoliberal policies, especially after the austerity that followed the 2008 financial crash, as well as the consensus that “light touch” regulation and neoliberal reforms that encouraged financialisation of the economy was responsible for that crash.

Though Thatcher and Reagan each delivered economic growth and undid stagnation brought about by leftist governance, their reforms led to little long-term benefit except for the rich. Decades of stagnant wages for the middle class, combined with the open immigration policies neoliberals tended to favour, has fuelled populism to their right directed against free trade, mass-immigration and the hollowing out of the White working class. Trump’s easy victory over a Republican field clinging to the Reaganite consensus that then gripped the party forced conservatives to adapt to his rhetoric of economic nationalism and populism, with National Conservatism emerging as the new trend among rightist intellectuals and leaders who successfully navigated this period, like Viktor Orbán.

Conclusion: Is There No Alternative?

There are a number of geopolitical reasons why global liberalism is declining. Still, in the West, this social liberal consensus remains strong. When it does come apart, it won’t be the result of a better idea winning the debate. The great source of instability is the millions of non-Western immigrants who have been brought to the West in recent decades. Multiculturalism has destroyed social capital in Western countries, to the point that conflict experts like David Betz now believe there is a strong likelihood of violent internal conflict coming to a European country in the next five years.

Both the emergence of this kind of planetary politics, and the source of its eventual undoing, was identified by Panagiotis Kondylis, a Greek-German sociologist I have previously written about. At the turn of the milennium, Kondylis had identified mass-immigration, facilitated by the naive human rights universalism and economism of Westerners, would contribute to massive conflict in the future:

Kondylis knew that mass migration into Europe, combined with having a demographic imbalance in native populations, would cut too deep into established normality with the possible consequence of the re-occurrence of things of the past: life-threatening scarcity and, as a consequence of it, a biologization of the political, meaning a re-shaping of the political along the lines of ethnic and tribal identities.5

Recently, there has been a recognition from social liberals like Keir Starmer that the “open borders experiment” was a failure — one which will lead to an “island of strangers” and a collapse in the social democratic institutions of Britain if not corrected. But men like Starmer will not remedy the problem. In their commitment to human rights universalism, Starmer’s Labour government will not even leave the European Convention on Human Rights, a self-imposed restriction which forbids them from even deporting the hundreds of illegal migrants arriving to their shores on boats every day.

As Western societies become increasingly racially diverse and politically fragmented, human rights universalism and pluralism, the underlying ethic of the social liberal consensus, will fade away as groups turn to an honest assertion of their racial and ethnic interest. Whites may be the last group to think in this way on a large scale, but the transition is already happening. After that, the future system that will rule the West, or whether there will be any such system for the whole West again, will be an open question. The future is unclear. What is clear is that the current order, for all its triumphs, rests on a precarious foundation — one that will not withstand the tensions it has itself created.

Rawls, John. "Justice as fairness: A restatement." Erin Kelly/Harvard University (2001). Pg. 131.

IBID. 137-138.

IBID. Pg. 139.

Alesina, Alberto F., Edward L. Glaeser, and Bruce Sacerdote. "Why doesn't the US have a European-style welfare system?." (2001).

Edinger, Sebastian. “Kondylis’s Theory of Planetary Politics. A Short Introduction.” reservatio mentalis Substack, March 9, 2024.

Ultimately (in my veiw) Liberalism sows the seeds of its own destruction.

Fascinating analysis Keith. Thanks for everything you do.

May just mention a good book I'm halfway through, called 'Against Liberalism' by Alain de Benoist.

The only alternative is localism which is the future of humanity as late modernity destroys birth rates