What is Table Talk?

Hitler’s Table Talk is a collection of informal monologues given by Adolf Hitler during meals at his wartime headquarters between 1941 and 1944. These conversations, recorded by members of his inner circle, ranged from religion and race to history, architecture, and war strategy. The tone was often speculative and rambling, which fits with Hitler’s style of monologue as many of his contemporaries described.

These comments were not recorded using shorthand or audio equipment. Instead, they were written down after the fact by members of Hitler’s inner circle, most notably a lawyer named Heinrich Heim, legal assistant Henry Picker, and later Martin Bormann, Hitler’s powerful private secretary and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. The note-takers worked under Bormann’s direction, who aimed to preserve Hitler’s musings as an ideological guide for the future. In the postwar years, these notes were edited, translated, and published in various forms, including French and English editions, and became an important source to historians reconstructing Hitler’s ideology and his thinking during this pivotal period.

Sources of Skepticism

Table Talk's legitimacy is often contested by revisionists who seek to downplay or deny aspects of Hitler’s ideology that it reveals. I encountered this after writing my article Nationalism Doesn't Need National Socialism, which cited Table Talk to explain Hitler’s intention to ethnically cleanse Eastern Europe. Most revisionists who reject Table Talk are motivated by one of two recurring concerns:

They reject Hitler’s hostility toward Christianity which is spelled out most clearly in Table Talk. Some of these are Christian National Socialists, and some like Richard Carrier are atheists who wish to argue evils of National Socialism came from Christianity.

They deny Hitler’s view on the inferiority of the Slavic races and his intention to subjugate and ethnically cleanse Slavic peoples.

Why does Table Talk pose a problem for them? Consider the following statements attributed to Hitler regarding Christianity:

The heaviest blow that ever struck humanity was the coming of Christianity. Bolshevism is Christianity's illegitimate child. Both are inventions of the Jew.

Christianity is a rebellion against natural law, a protest against nature. Taken to its logical extreme, Christianity would mean the systematic cultivation of the human failure.

The reason why the ancient world was so pure, light and serene was that it knew nothing of the two great scourges: the pox and Christianity. Christianity is a prototype of Bolshevism: the mobilisation by the Jew of the masses of slaves with the object of undermining society. Thus one understands that the healthy elements of the Roman world were proof against this doctrine.

On Hitler’s view of the Slavs, Table Talk makes it clear that he viewed them as an inferior race worthy of and destined for subjugation under Germans:

The Slavs are a mass of born slaves, who feel the need of a master.

The Russian will never make up his mind to work except under compulsion from outside, for he is incapable of organising himself. And if, despite everything, he is apt to have organisation thrust upon him, that is thanks to the drop of Aryan blood in his veins. It's only because of this drop that the Russian people has created something and possesses an organised State.

We'll take the southern part of the Ukraine, especially the Crimea, and make it an exclusively German colony. There'll be no harm in pushing out the population that's there now.

It should be possible for us to control this region to the East with two hundred and fifty thousand men plus a cadre Of good administrators. Let's learn from the English, who, with two hundred and fifty thousand men in all, including fifty thousand soldiers, govern four hundred million Indians. This space in Russia must always be dominated by Germans. Nothing would be a worse mistake on our part than to seek to educate the masses there. It is to our interest that the people should know just enough to recognise the signs on the roads. At present they can't read, and they ought to stay like that.

Carrier and Nilsson

The two scholars most credited for their challenge to Table Talk authenticity in recent years each seem to have been motivated by a desire to preserve the idea that Hitler was a believing Christian. Richard Carrier is a Jesus mythicist who wished to counter the arguments of Christians that Hitler shared his atheism. Carrier wrote a series of articles investigating problems with the sources used in Table Talk. However, he concluded that there were three German versions that "have a common ancestor, which must be the actual bunker notes themselves”. His investigation concluded with a note of caution about the documents and a recommendation that scholars work with the German editions to avoid later editorial additions.

Table Talk was dissected much more rigorously by the historian Mikael Nilsson, who has also argued for Hitler being a believing Christian on the basis of his public statements. Nilsson’s 2020 work Hitler Redux is a very thorough investigation of the editorial history of Table Talk. The history of the Table Talk itself turns out to be quite an interesting chapter of history as Nilsson traces the many editorial distortions introduced over time and how these were often treated uncritically in historical literature. Nilsson argues that although Table Talk document real conversations with Hiter, the published versions we have are layered with editorial decisions that compromise their reliability as direct sources, but historians have often treated them as verbatim recordings on the assumption they were from stenograph recordings.

A Brief History of Table Talk

The initial note-taker for Table Talk was Heinrich Heim, a lawyer who worked under Bormann. He recorded Hitler’s comments from mid-1941 through early 1942. Heim typically jotted notes or reconstructed full summaries after the conversation had ended.

Heim was succeeded by Henry Picker, who continued the project into 1943. Picker later published his version in German in 1951. Unlike Heim, Picker inserted clarifying remarks, removed repetitions, and polished Hitler’s language. While both Heim and Picker were present for Hitler’s conversations, their transcripts reflect differing levels of editorial intervention and personal interpretation, something Nilsson zeroes in on to emphasise the unreliability of Table Talk for providing verbatim quotes.

Later, parts of these notes were assembled and edited again by Martin Bormann himself, who had initially commissioned the project. In the postwar period, the most widely circulated editions were produced by François Genoud and Hugh Trevor-Roper.

Editorial Layers and Their Problems

Mikael Nilsson's Hitler Redux does valuable work documenting the serious editorial issues with the many published versions of Table Talk. These problems are present in each of the three main editions:

Henry Picker's 1951 German edition removed repetitions, polished language, merged material from different dates, and contained what even Bormann identified as numerous errors and misdatings. Despite these flaws, it became the standard German reference for decades.

François Genoud's 1952 French edition presents more serious concerns. Genoud was a postwar Nazi sympathiser who acquired the rights to the Table Talk documents after the war. Genoud had a track record of manipulating other Hitler documents, which raises red flags about his input on Table Talk. Genoud closely safeguarded the original German manuscripts, refusing to grant access to scholars and making independent verification of his production of Table Talk impossible. Nilsson documents how Genoud arranged secret contracts to ensure everyone involved in producing the later English edition — a team led by the renowned Hitler historian Hugh Trevor-Roper — could only use his French version as their base text.

Hugh Trevor-Roper's 1953 English edition compounded these problems by translating not from the original German manuscripts but from Genoud's own questionable French version. This created multiple layers of potential distortion: a post-facto recollection, editorial smoothing, the ideological motives of Genoud, translation and retranslation to French and then to English.

The Best Available Source Solves Most Problems

But most of these issues which Nilsson's book investigates at length can be avoided simply by using the most reliable edition available: the 1980 version edited by Werner Jochmann, which has been carefully reconstructed from Bormann's archives using Heinrich Heim's original notes as the primary source.

This edition eliminates the editorial problems that plague other versions. It sidesteps Picker's stylistic interventions and date-merging. It avoids Genoud's potential ideological manipulations entirely. It eliminates the translation-retranslation chain that distorts the Trevor-Roper edition. Most importantly, it preserves Heim's systematic approach to note-taking, including his careful acknowledgment that entries were reconstructed rather than transcribed.

Heim remains the most credible of the original note-takers. He worked closely with Bormann from 1941-1942, was trusted within Hitler's circle, and maintained a consistent methodology. His notes, as preserved in the archives and presented in the Wirth edition, represent the earliest and least adulterated layer of documentation available.

However, because they were reconstructed from memory and not taken down in real time, they inevitably reflect at least some editorial interpretation in how to reconstruct the conversations. We can reasonably conclude that while not verbatim, they offer a reliable reconstruction of Hitler’s private statements. And that is all any mainstream historian who uses the Table Talk expects — it has not been treated as a verbatim recording of Hitler’s words by reputable historians for some time.

In fact, Nilsson himself, despite documenting the editorial problems extensively, still emphasises the fundamental authenticity of the source in the conclusion to Hitler Redux:

However, and this is very important, the results presented in this book should absolutely not be interpreted as meaning that the table talks are not authentic. They really are, at least for the most part, memoranda of statements that Hitler made at some point or another in his wartime HQs. They were made by either Heim, Picker, Müller, or Bormann, although there are also some notes that have no name attached to them.1

Nilsson does NOT claim that Table Talk is fabricated or worthless. His concern is that it has often been used without sufficient attention to its origins. As his exhaustive account of the history of the Table Talk show, many postwar writers have unquestioningly treated Table Talk as if it were a stenographic transcript, which it is not.

Now compare this statement of supposed arch-skeptic Nilsson to what a very mainstream historian of the Third Reich, Richard J. Evans, says in defence of the source's reliability:

These were, then, not based on shorthand transcripts taken by Hitler's secretaries, as has sometimes been assumed, but written up after the event. How reliable are they? Obviously, they are not an exact record, and indeed Heim prefaced each of them with a phrase such as 'The boss expressed himself among other things, in effect, as follows.'

Moreover, while Bormann was satisfied with Heim's reports, he was far more critical of Picker's, which contained numerous minor slips and even misdatings and mistranscriptions. However, there is no evidence that anyone, including Bormann, interpolated new material or inserted tendentious amendments in order to give readers a false impression of Hitler's views. After all, by 1941 Hitler was regarded, not least by his staff and by Nazi fanatics like Martin Bormann, as a kind of God, and the actual reason for recording the 'table-talk' was to put down his thoughts as a kind of sacred text, a guide to the imagined Nazi future. Altering the record in any significant way would have been tantamount to sacrilege.

Of course, Hitler can hardly have expected his listeners not to repeat what he said to others, so his remarks were far from being private or confidential. But nothing in the 'table-talk' went in any way counter to Hitler's known views as expounded in his speeches and directives, and the frequent repetitions and revisits to previously discussed topics reveal complete consistency in what Hitler said during the period of time covered. They add details to what is already known but contain no startling revelations. It does not follow from the fact that they were written up from memory that they did not more or less faithfully reproduce anything Hitler said, or distorted or misrepresented his thoughts.2

Even the most skeptical critiques of Table Talk, such as those by Nilsson and Carrier, ultimately arrive at a broadly similar conclusion.

Bormann and Hitler’s Christianity

The real question is how likely it is that Bormann manipulated the texts to lie about Hitler’s true beliefs. As Evans points out, Bormann would have seen this as a sacred text necessary to preserve Hitler’s original thoughts in as original way as possible. Carrier challenges Bormann’s reliability by suggesting he was part of a small, ideologically anti-Christian minority within the Nazi leadership, and thus, as Carrier sees it, had reason to hide Hitler’s Christianity:

There really were notes taken down in Hitler’s bunker of things he was remembered to have said, by people who were there, and those notes were really collated and heavily rewritten by Hitler’s secretary Martin Bormann (notably, infamously, a Christian-hating atheist; there were some of those in the Nazi party, though they were fairly rare, and Hitler wasn’t one of them). And all the varying published German versions do derive from that Bormann manuscript in one way or another.

Similarly, Nilssen quotes Picker, who said of Bormann that he took his notes and “edited them in a shameless manner”, this is followed by Nilssen noting that “if there ever was a National Socialist who hated Christianity it was Bormann.” So should we be skeptical of the anti-Christian passages in Table Talk as the manipulation of Bormann?

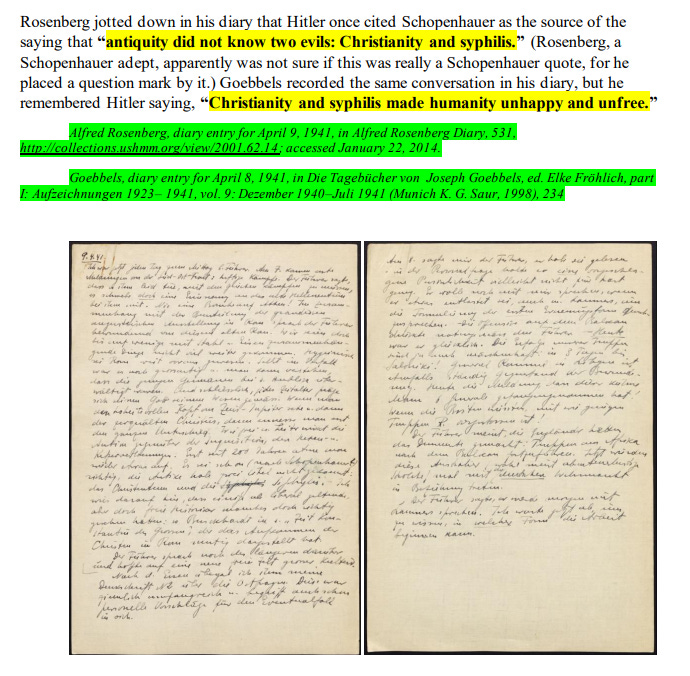

Recall one of the harshest anti-Christian quotes from Table Talk cited earlier, where Hitler is reported to have said “The reason why the ancient world was so pure, light and serene was that it knew nothing of the two great scourges: the pox and Christianity.” “The pox” here refers to syphilis, and we have testimony from the diaries of both Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels recording the very same statement from Hitler in April of 1941:

If we have primary sources from Hitler’s closest inner circle attesting to an anti-Christian statement recorded in the Table Talk, then the claim of people like Carrier that Hitler’s anti-Christian statements point to manipulation by Bormann falls apart. Perhaps Bormann could have made some of Hitler’s anti-Christian statements stronger, but the idea he was fabricating things is just not supported by the evidence, and the single strongest anti-Christian statement we have from the document is confirmed genuine by the other diaries. But another that point people throwing doubt on Bormann seem to miss is he would only have edited the Table Talks on the assumption that Hitler would be dead when they were published and thus unable to call him out on falsifications. They are looking back on how the war turned out as if Bormann knew Hitler faced an inevitable demise in 1945. But had Hitler survived, he could easily have called out misrepresentations of his worldview in the talks, something Bormann was aware of.

Finally, the evidence that Carrier and Nilsson draw on to argue for the likelihood of Hitler’s religiosity against Table Talk is drawn mostly from public speeches by Hitler, where he was appealing to a heavily Christian German public. We would have to expect a politician like Hitler to temper his anti-Christian attitudes when speaking to a mass audience.

In sum, while Table Talk is not a verbatim record of Hitler’s conversations, it remains a credible and valuable source for understanding his private beliefs. Since it aligns with other primary accounts and private testimony, and no compelling evidence suggests Bormann distorted Hitler’s views, the major objections against its authenticity collapse under scrutiny. The editorial issues documented by Nilsson are real but do not undermine the fundamental authenticity of the material.

The note-takers for the Table Talks were present at the events they recorded. While their reconstructions weren't perfect transcripts, they were eyewitness accounts by people with direct access to Hitler's private conversations. Used critically and with proper sourcing, Table Talk remains among the most illuminating records of Hitler’s worldview.

Nilsson, Mikael. Hitler Redux: The Incredible History of Hitler’s So-Called Table Talks. Routledge, 2020. Pg. 388.

Evans, Richard J. Hitler's people: the faces of the Third Reich. Random House, 2024. Pg. 6 & 7.

Excellent little piece of research, thank you

Hitler's hatred of Christianity has been proven completely valid by time. Christians overwhelmingly these days revere Jews and negroes. They are one of the primary importers of negroes and Hispanics to Europe and Mexico respectively.

Christian churches were instrumental in browbeating white southerners into accepting the civil rights regime and Afrikaaners into accepting black majority rule.

Christians also regularly sabotage white collectivizing by prioritizing religion over race. Look at E. Michael Jones, Sarah Stock, and the other trad caths.

And they are right to do so. Christianity is not a racial religion and its about this world. This world is after all fallen and the domain of Lucifer. Their main focus is on the next world and living a virtuous life.

It makes perfect sense for a Christian to go to Africa and feed the blacks and explode their population further. They are saving ''God's children''and bringing more of them into the world.

As for Slavs, Hitler's views on them changed later on. He in fact even said that the future of Europe will belong to the stronger men of the East and that Russians would become the dominant power down the line.

He also spoke highly of Poles later on and praised their creative ability, and called for their incorporation into the Reich.

https://qr.ae/pAjV8s

These quotes come from the table talks which you are citing.