Richard Hanania penned an article titled The System Everyone Hates Is the One That Has Actually Worked, intended as a defence of every leftist college professor’s favourite ideological punching bag — neoliberalism.

Hanania prides himself on attacking the populist beliefs of the left and right alike in favour of the “elite human capital” beliefs which defend liberty, markets, and colourblind meritocracy. His case for neoliberalism is simple: “Neoliberalism emerged to deal with real problems, had strong intellectual foundations, and largely accomplished its goals.”

Hanania’s argument after this depends on cherry-picked data, misleading comparisons, the ignoring of obvious counter-arguments and examples, and a simplistic set of myths about markets and fiscal prudence that would fit a Sean Hannity monologue better than a serious think-piece. Rather than demonstrating that neoliberalism “worked,” Hanania only reveals how shallow its intellectual defenders have become.

Hanania’s case is wrong in many ways, so I will break it down based on each of his major claims about economic history.

1. Neoliberalism delivered massive growth to those who embraced it.

Hanania writes that “the UK, in particular, saw growth increase in the 1980s and 1990s. Growth was about the same in the US in the 1980s and 1990s as it was in the 1970s, but with lower inflation, more stability, and lower unemployment. Refusing to follow Thatcher’s approach of taking on unions and limiting the expansion of the welfare state, the other major economies of Western Europe—France, Germany, Italy, and Spain—saw slower growth than either the US or the UK in subsequent decades.”

It’s not true that this period saw higher growth than the Keynesian post-war period. According to data from Crestmont Research, US GDP growth averaged 3.97% in the decades of the 1950s, 60s and 70s; and just 2.73 percent in the three subsequent decades. The picture is similar for the UK: ONS data shows average GDP growth of 4% from 1950 to 1979, and just 2.7% in the period Hanania celebrates from 1980 to 2009. Hanania is only calling these growth rates impressive compared to a period of economic crisis that came at the tail-end of the Keynesian period, which is hardly a fair way to judge its success. This would be like comparing the growth rates of the 1960s to the two years after the neoliberal financial crisis of 2008.

And just looking at GDP growth rates to judge the success of policies in this period is misleading. After all, exogenous factors — like a windfall of natural resources — can grow the economy in spite of bad government policy. Other bad policy, like borrowing from the future with heavy deficit spending and private credit expansion, can also lead to impressive GDP growth without actually being the best way to steward the economy. Both of these apply to Thatcher and Reagan’s economic management.

Reagan’s economic miracle, apparently built on financial prudence and the rolling back of big government, was financed by the largest peacetime deficits in American history up to that point. Federal debt as a percent of GDP almost doubled during Reagan’s time in office, as he embraced cutting tax revenue alongside a surge in military spending, and in nominal terms the national debt tripled due to his deficit spending. Pumping money into the economy through deficit spending is textbook Keynesianism, but the difference is Reagan’s policies focused on pushing consumption with borrowing while replacing manufacturing exports and real productivity gains. At the same time, financial deregulation and credit expansion encouraged an explosion of private debt.

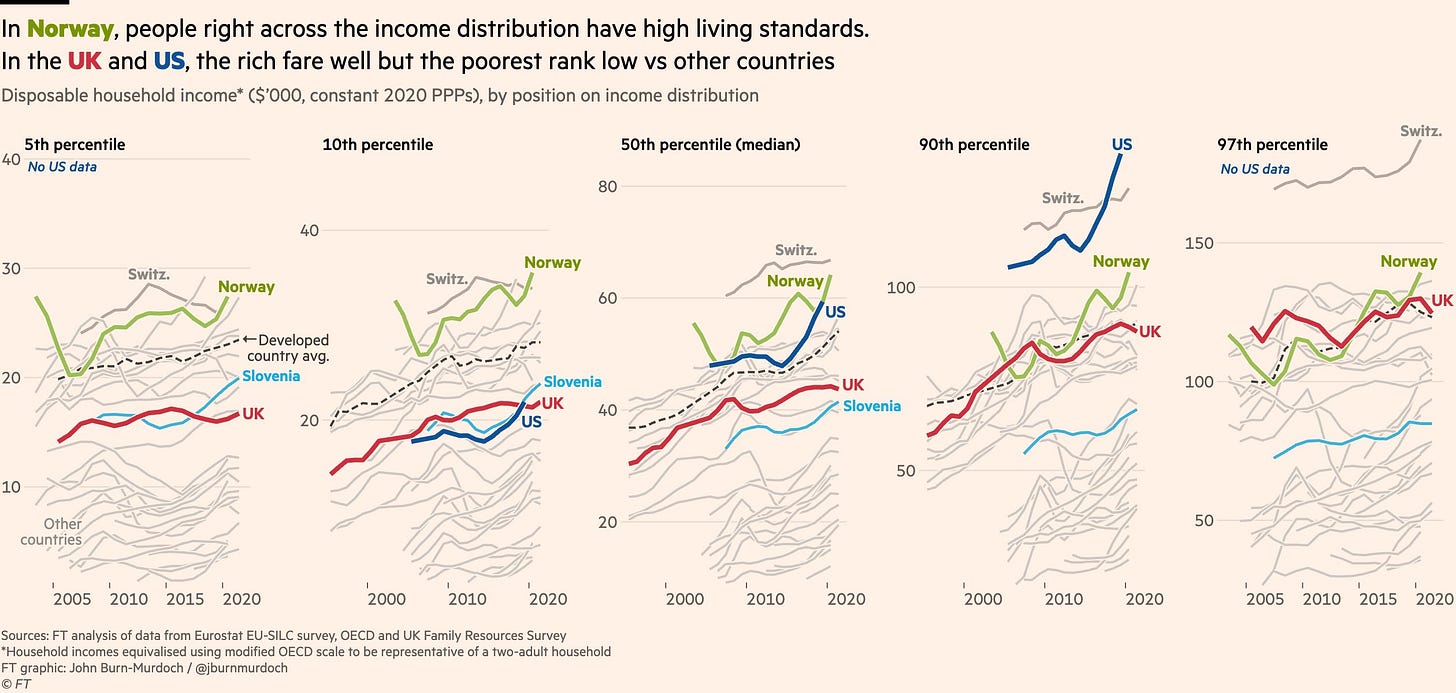

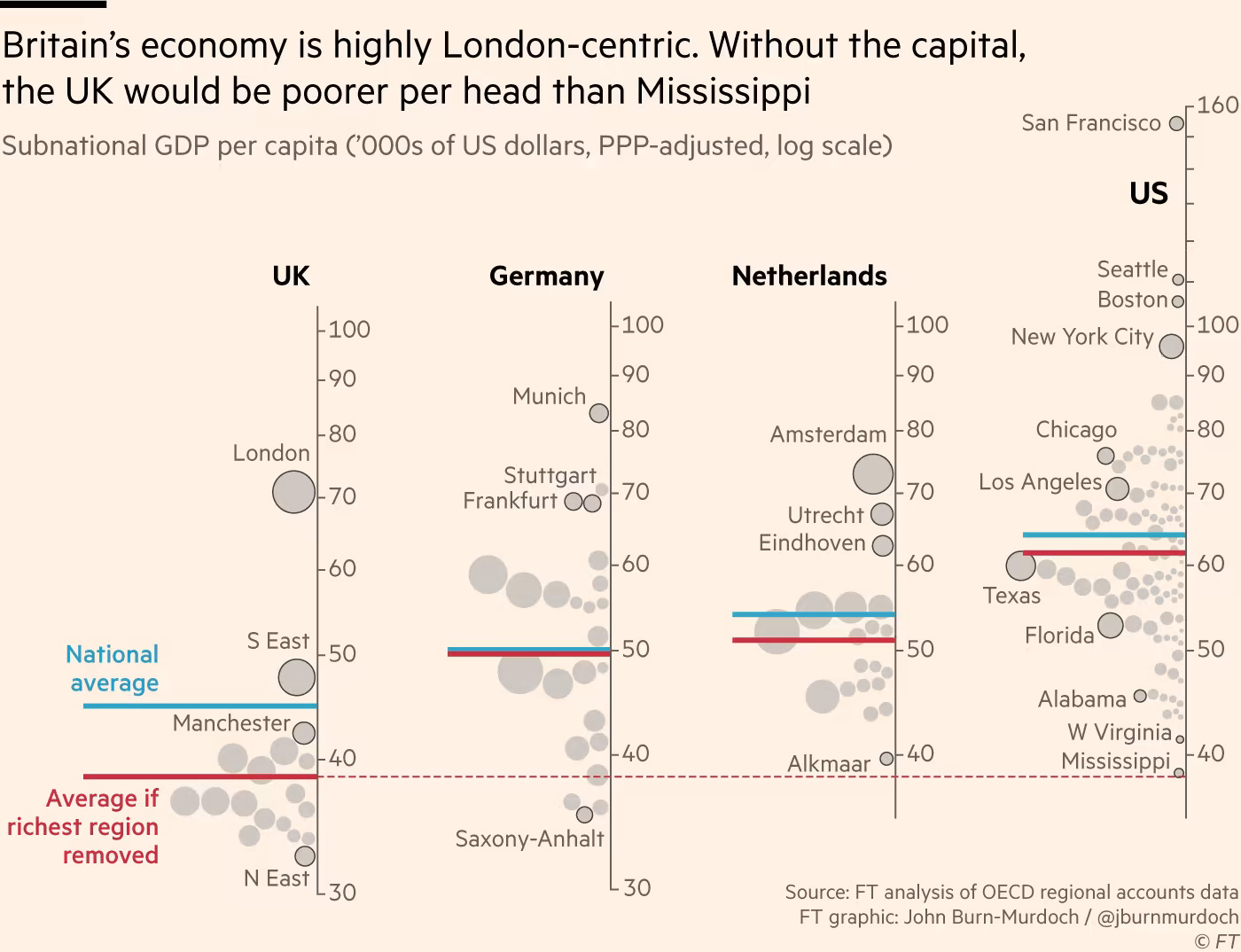

Similarly, Thatcher’s apparent revival owed much to the North Sea oil boom and financialisation of the British economy, which in the long-run would become a drain on Britain’s productive economy. The North Sea oil find was generating 3% of national income in the Thatcher years, a figure which would “conservatively” be valued at £450bn by 2008 if invested in safe assets as more prudent socialist countries like Norway did with their resource wealth. Elsewhere, I have written in detail about the myriad of ways Britain’s turn to financialisation under Thatcher has made it worse off, to the point where the British middle-class now has a lower living standard than Slovenia and is on course to be overtaken by Poland.

Modern Britain now has fewer IPO’s than Mexico, with an economy almost entirely reliant on financial services. And if you exclude the international financial hub that is London, the remainder of Britain is poorer than every state in the US, as well as all the European countries Hanania talks about it outperforming.

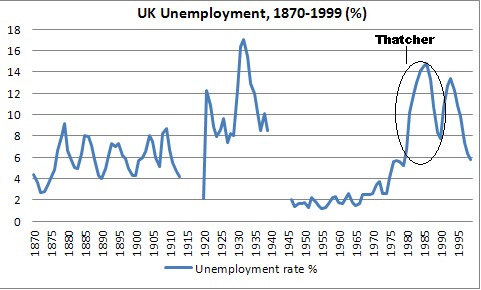

Thatcher’s oil money created the illusion of a productivity revolution that was simply downstream of an explosion in energy revenue and asset inflation. Thatcher also deregulated markets in a way that ignited a wave of speculative capital inflows and property bubbles that pumped up GDP figures but added little to the real economy other than pricing out would-be home buyers. Hanania suggests neoliberal policies solved the unemployment problem it inherited, yet unemployment actually worsened under Thatcher. After inheriting an unemployment rate of 5.2% in 1979, unemployment rose to as high as 14.8% in 1986, well into Thatcher’s term, and was still at 7.7% by the time she left office.1

Hanania’s claims about growth don’t even stand up on the numbers, but in both of the examples he uses that growth was short-term and fuelled by debt, natural resource revenue, public asset fire-sales and government spending, a package that was obviously unsustainable — and that’s before even getting to the role the deregulation of this period played in the ‘08 financial crash.

2. Neoliberalism is responsible for China and India’s development.

Hanania writes that “After market-oriented reforms, both nations experienced dramatic improvements in growth and poverty reduction.” He notes that China’s rise alone has accounted for nearly 75 percent of the global reduction in extreme poverty over the last four decades.

Now, to praise the success of neoliberalism, Hanania is citing two countries that explicitly rejected it in this period. Of course it’s true that market liberalisation helped develop both countries immensely, but neoliberalism isn’t just markets. All of the Keynesians of the post-war period would have supported China and India making market reforms and opening up to global trade. It wasn’t neoliberal economists that opened China up to the global marketplace, it was pre-neoliberal politicians like Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter and his Keynesian economic advisors. The great wave of Western capital that poured into China in the 1980s and 1990s came through diplomatic initiatives, export-credit agencies, and multinational investment guarantees, Western governments coordinated global economic integration rather than allowing markets to act spontaneously.

As for China’s domestic policy, China has embraced a very centralised form of economic corporatism (state-capitalism, if you prefer) which is closer to fascism than anything promoted by liberal ideologues. China maintains strict control on finance and runs state banks, for much of its development all land remained under state control, strategic industries were heavily subsidised rather than allowing the market to pick winners, and they were bolstered on the world stage by aggressive tariff policies and an intentionally undervalued currency.

3. Other East Asian economies had more success with more neoliberalism.

Hanania acknowledges China is a “hybrid model,” but points out that countries like Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan achieved even more economic prosperity embracing a more pure form of neoliberalism. This demonstrates a profound ignorance of the economic history of these countries. Hong Kong is obviously a special case as a sheltered city-state. Singapore, like China, is closer to corporatism than neoliberalism: this is a country where 90% of land is state-owned, where the state has near complete control of the housing market, and sovereign wealth funds own dominant shares in large industries — all policies which repudiate neoliberal prescriptions about leaving land, housing and industry to private interests.

South Korea and Taiwan also followed the course of developmental nationalism to achieve their economic miracles. South Korea under Park Chung-hee was a textbook case of corporatist economics: credit was directed by state-owned banks and the state selected “national champion” firms for export promotion like Hyundai and Samsung. Tariffs and import quotas were used to protect domestic industry until global competitiveness was achieved.2

South Korea, Taiwan, and then China all followed the model of infant-industry protection combined with export discipline, and only opened up to more competitive global markets when they had directed their industry to be in a strong enough position to win in a fair fight. Hanania writes that “It was beneficial for China to move away from communism, but its growth has likely occurred despite practices like large state-owned enterprises… rather than because of them.” What is this based on? Does he also think South Korea would have been better off without Samsung, LG and Daewoo?

4. “Shock therapy” was a success in the long-run.

Hanania also points to the post-communist transition in Eastern Europe as evidence that neoliberal “shock therapy” ultimately worked. He writes that although the reforms were painful in the short term, “over the medium to long-run, many of these economies stabilized, integrated into the European Union, and experienced sustained growth.” Not only does Hanania breeze over the astonishing scale of the initial collapse brought about by pursuing neoliberal prescriptions, but he ignores the fact that recovery for these countries only came after the abandonment of neoliberal orthodoxy.

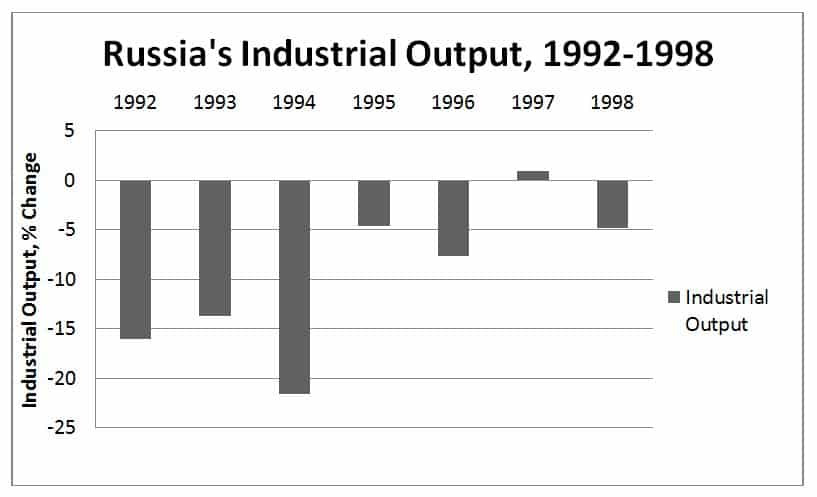

How bad was it? Between 1989 and 1996, Russia’s GDP collapsed by roughly 45 percent, industrial output by over half, and real incomes fell by around 40 percent. Inflation in 1992 alone exceeded 2,000 percent, wiping out household savings overnight. Male life expectancy dropped from 65 years to 57, a demographic collapse unprecedented in peacetime.

In Ukraine, GDP shrank by more than 60 percent during the 1990s under neoliberal shock therapy, and by the end of the decade, half the population lived below the poverty line. Merely some short term pain according to Hanania, who highlights Poland in particular as a post-communist success story. But Poland immediately relented on its initial shock therapy, reintroducing subsidies for key sectors, and kept large state firms under partial public control for another decade.3 These countries restored corporatist economic structures after the anarchic conditions of the early 90s, many benefited from massive EU investments, and others like Russia had a recovery led by commodity exports, not financialisation.

If Hanania was really judging neoliberal policy empirically, the post-Soviet experience should count as a massive failure. Instead, he gives a sentence to the catastrophe it engendered then credits all subsequent success after communism to the wholly unnecessary initial experiment with neoliberalism.

5. Neoliberalism brought greater economic stability.

Having done nothing to make his case for the empirical vindication of neoliberal ideas, Hanania now ponders why people reject it in spite of its obvious success. His answer is that it may be too successful. Economic instability was taken for granted in the old system because of the constant recessions, but Hanania writes that “the Great Recession of 2008 was a major exception, it stood out precisely because it interrupted what had become an era of relative economic stability compared to the turbulence of earlier decades.” Hanania then makes the astonishing claim that “The only other serious economic crisis since the mid-1980s was the COVID-19 downturn.”

While writing this, I saw the excellent X user Lord Keynes had published his own response on his economics-focused blog, which I highly recommend. I won’t do a better job compiling a list of neoliberalism’s own financial crises than he did:

Neoliberal Asset Bubbles and Financial Crises

(1) 1980s US Savings and Loan Crisis (1986–1995)

Financial deregulation and risky investments caused the failure of over 1,000 savings and loan institutions, which cost US taxpayers about $160 billion.

(2) 1990s Japanese Real Estate Bubble and Lost Decade (1990–2000s)

Financial deregulation in Japan led to a massive real estate and stock market bubble, followed by bank crises, banking failures, and recession.

(3) 1990s East Asian Financial Crisis (1997–1998)

Capital control liberalisation and financial deregulation allowed asset bubbles and capital inflows, which then catastrophically reversed, as well as speculative attacks on national currencies in Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea, and other nations.

(4) Dot-Com Bubble (1999–2000)

(5) 2008 Global Financial Crisis (2007–2009)

Neoliberal financial deregulation allowed a massive real estate bubble, with toxic subprime mortgage defaults, a global financial crisis and the worst global recession since the Great Depression.

(6) The Eurozone sovereign debt crisis (2009–c. 2015)

The fundamental cause of the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis and the bad deflationary recessions and/or banking crises during this period – in Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Cyprus, Spain and Italy – was ultimately the flawed Neoliberal design of the EU and Eurozone monetary policies: the Eurozone effectively robbed smaller nations of monetary sovereignty, which drove them into brutal austerity that, most notably, crippled the economies of Ireland and Greece.

What makes this record even worse is that neoliberal dogma often prevented effective responses to these crises. Governments constrained themselves with austerity, inflation-targeting, and faith in market self-correction. After 2008, governments engaged in costly bailouts of the financial system they had let run wild with the light-touch regulation encouraged by neoliberalism, forcing fiscal restraint on public finances that led to a decade of stagnation.

In Europe, the neoliberal architecture of the Eurozone turned a private banking crisis into a sovereign-debt crisis, which has been a massive drag on public finances and growth ever since. Instead of stabilising capitalism, the commitment to neoliberalism has slowed or sabotaged recovery by subordinating national prosperity to the preservation of financial orthodoxy.

Conclusion

Intellectuals often display a peculiar laziness when they turn their pen to economics. Part of this, I think, is they are too focused on ideology at the cost of taking a cold look at the historical record. Hanania loves the idea of neoliberalism, but he is clearly ignorant of the record of the system he is volunteering to defend.

Hanania’s whole case is a series of myths: that Thatcher and Reagan rescued capitalism through discipline and faith in individualism; a simple story of China’s ascent being about capitalism replacing statism; that the East Asian economic miracles were the product of laissez-faire economics rather than protectionism and state-direction; that the wreckage of post-Soviet shock therapy — the single greatest peacetime economic collapse in modern history — was a necessary reform after communism; and that the neoliberal era brought stability and prudent financial management despite hollowing out native industry, stagnating living standards for the middle-class, and leaving us with the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

If there’s a lesson from economic history, it’s that ideology is a poor guide. The most enduring systems are those that allow markets to channel ambition and creativity, but draw pragmatic boundaries when they threaten the stability of families, industries, or the nation itself. Hanania may want to live in a world that has outgrown the nation-state, but the economic history of the 20th century shows that what really “works” is nations using markets rather than surrendering to them.

Boyer, George R., and Timothy J. Hatton. “New estimates of British unemployment, 1870–1913.” The Journal of Economic History 62, no. 3 (2002): 643-675.

Jwa, Sung-Hee. “What Made Possible the Korea’s Economic Miracle?: Park Chung Hee’s Economization of Politics, Economic Discrimination and Corporate Economy.” Review of Institution and Economics 17, no. 1 (2023): 1-38.

Hall, Thomas W., and John E. Elliott. “Poland and Russia One Decade after Shock Therapy.” Journal of Economic Issues 33, no. 2 (1999): 305–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4227441.

I think Richard is some kind of natural contrarian. (I know because I am one myself.) He's spent so much time on RW social media he begins to think the whole world is RW social media, so now his contrariness kicks in and next thing you know he's sounding like a teabagged David Brooks to "own the RW". I don't think he's stupid, he's just reacting to what he sees online and feels compelled to countersignal. If X suddenly became the Twitter of 2020 then Richard would get based again.

That said, I don't trust people that have been redpilled but then find their way back to liberalism. I don't know how that is possible unless they've been given donor bucks, which is possible with Richard.

I was born in Barking. Today it looks something between Karachi and Mogadishu.

This isn't progress.