Fact Checking Europa: The Last Battle | World War 1

German Militarism, Peace Offers & The Balfour Declaration

Read the first parts of this series here.

Watch the film and follow the timestamps here.

Throughout World War 1, Germany wanted peace and had nothing to gain from the conflict (1:15:55)

Although assigning blame to any individual countries for the outbreak of WW1 is very difficult, there is no doubt Germany deserves a good portion of blame for its decision to give Austria-Hungary a “blank cheque” to respond to Serbia in July 1914. A big part of this calculation was the belief among German leadership that there was a closing window where it could challenge the French-Russian alliance before Russia’s industrialisation made them unchallengeable.

General Helmuth von Moltke, Chief of the German General Staff from 1906 to 1914, was convinced from well before the war that only a defeat of Russia could secure Germany’s future.1 This was a fear that was exacerbated by Russia launching a big program of rearmament after the disastrous Russo-Japanese War in 1913, that was due for completion in 1916-17.2

One of Germany’s generals in the war, Friedrich von Bernhardi, wrote a bestselling book titled Deutschland und der Nächste Krieg (Germany and the Next War) in 1912. Although von Bernardi was fairly distant from German high command, his arguments about Germany’s inevitable choice between ‘World Power or Decline’, “epitomised the intentions of officials in Germany’s military leadership with great precision.”3

Bernardi’s argument was that Germany could only compete as a world power if it eliminated France as a threat, acquired new colonies, and took leadership over other Central European countries into a federation — 'Mitteleuropa'. Only this would allow Germany to compete with both Russia and the established world powers of the United States and the British Empire, who held far greater territory than Germany which had been late to colonialism.

In line with this thinking, during the war many in German leadership favoured policies of annexation and colonisation of the east. In 1914, the Chancellor of Germany tasked Friedrich von Schwerin with working out a plan for governing Germany’s captured territory in the East. His chief proposals were:

The annexation of the Polish 'Frontier Strip' and of the provinces of Lithuania and Courland, in which he proposed to carry through an extensive settlement scheme with colonists from the interior of Germany and from Russia.4

In March 1915, von Schwerin issued a 30 page memoranda to the government advising on occupied North-Eastern territories, wrote that:

The German people, the greatest colonising people of the world, must be mobilised again for a great operation of colonisation, it must be given wider frontiers within which it can live a full life. The overseas territories suitable for colonisation by Germans have already been distributed, and cannot be acquired as prizes of victory in this war, so that an attempt must be made to acquire new land for settlement contiguous with the present Germany.5

A further report on the occupied territories submitted to the government by Geheimrat Sering after the foreign ministry sent him to modern day Lithuania and Latvia with the task of writing a detailed report on how to settle Germans in the Baltic region. Sering argued that the great world powers — the British Empire, the United States, Russia — attained their power because of their great expanse of living space for their core population (with Britain’s smaller size overcome by its White colonies). Sering informed the government that Germany was destined to be confined to a secondary status on the world stage if it did not expand its heartland, and this could only be done by annexing land to its East.

Sering thus proclaimed it the ‘holy duty’ of the Fatherland to settle this new ‘Ostland’ in the Baltic region with two million ethnic Germans uprooted by the war.6 In Sering’s words:

The present war, unleashed by the Europe-based giant empires against the Central Powers, will decide whether the latter, and the countries of Central Europe as a whole, can continue to exist at the side of the giants as their equals, or not. They can do so only if the map is altered very radically in their favour.7

Both of these reports and their recommendations were very influential on German policy, and the views of their authors reflected the consensus of Germany’s military leadership.

Without even getting into the debate of where blame lies for the First World War, there is no doubt that once it exploded, German military leadership sought to make the best of it, decapitate its main continental rivals, expand German borders, and finally establish Germany as a world power.

Even though Germany was winning in December 1916, Kaiser Wilhelm made a generous peace offer anyway (1:16:01)

Europa says that “Kaiser Wilhelm was willing to just call off the war and return to how things were before”. Not so. The peace proposal approached the Entente powers from the position of assumed victor. At the time, Germany occupied Belgium, Poland and areas of France, with no mention in their proposal of leaving these countries to “return to how things were before”.

In fact, the Central Powers never expected the peace offer to be accepted. Instead, it was a propaganda tool and a means of quelling anti-war sentiment in Germany. The German chancellor at the time, Bethmann Hollweg, admitted in a letter that the intention was for the Entente to reject the proposal, thus shifting blame to them for the hardships caused by the war:

Should our enemies refuse to enter peace negotiations – and we have to assume that this will be the case – the odium of continuing the war will fall on them. War-weariness … will then grow and generate new support for the elements that are pushing for peace. In Germany and among its Allies, too, the desire for peace has become keen. The rejection of our peace offer, the knowledge that the continuation of the struggle is inevitable thanks alone to our enemies, would be an effective means of spurring our people to utmost exertion and sacrifice for a victorious end to the war.8

Hollweg had also written to Hindenburg before the proposal, accepting Hindenburg’s demands that any German terms for peace include the right to militarily occupy Belgium, the annexation of the Briey-Longwy region and other areas of France, an indemnity paid to Germany in exchange for evacuating France, the annexation of Luxemburg and the acquisition of the Congo.9 In the final proposal:

The two most outstanding characteristics of the note are its vagueness and its defiant tone. Such overbearing language did anything but convey a willingness to make concessions in return for an early peace.10

As well as simply hoping for positive psychological effects among the German public:

The hope of achieving a separate peace with one partner or another was the real motive behind the whole move, for hardly anyone seriously expected the peace offer to be accepted.11

So Germany’s peace proposal wasn’t really aimed at peace, and still expected any party to it to accept large territorial gains and monetary compensation to Germany as a prerequisite to entering discussions.

The other part of Europa’s narrative here is that by December 1916 Germany was clearly winning the war. It mentions Britain suffering from the U-Boat campaign, France suffering heavy losses, Russia’s internal strife, and the fact that none of Germany had been militarily occupied. Thus, we are set up to believe that only the Balfour Declaration and subsequent US entry into the war staved off inevitable German victory.

By this point in the war, the Royal Navy had control of the North Seas and was blockading Germany, causing bad food shortages — the “turnip winter” of 1916-1917 was actually the low point in German food supply during the war.12 The Entente’s naval blockade of Germany was far more crushing than Germany’s U-Boat blockade, and low morale in Germany and growing calls for peace led to efforts like the peace note. At this point in the war, after the Somme and Verdun offensives, the war was at a stalemate. Europa mentions the heavy losses France had suffered, but there were more dead German soldiers than French at this point in the war, and the Allies retained greater manpower than the Central Powers.

The Allies were also outproducing the Central Powers militarily and economically, and growing their advantage. This was a trend that continued throughout the war.13 Already by the start of the war, the Triple Entente accounted for 28 per cent of the world’s manufacturing output compared to the Central Powers 19. The Allies also had a 4.5:1 population advantage which translated to a military manpower advantage. Even Germany’s knocking Russia out of the war was more than compensated by the combined growth of the Allies’ output and decline of the Central Powers during the interim period.14 Given these disadvantages, few historians now believe Germany ever had a realistic chance of winning World War 1.15

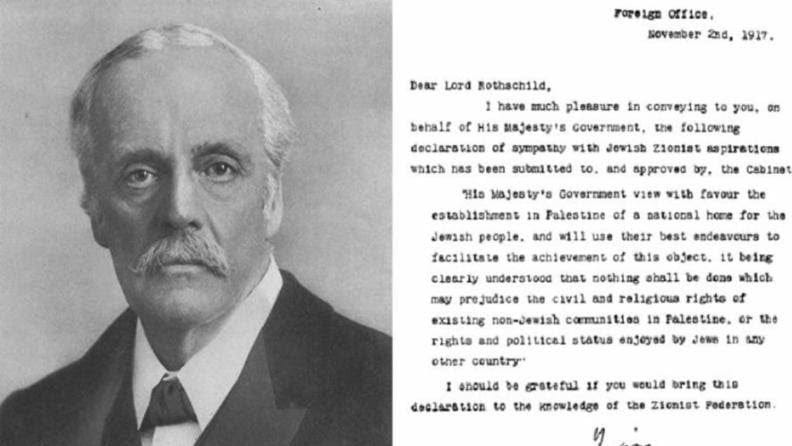

Jews offered to secure US entry into WW1 in exchange for a Zionist state (1:16:38)

Securing Jewish Zionist influence on the side of the Allied Powers was undoubtedly a calculation for the British in making the Balfour Declaration. Lloyd George told his cabinet that:

The Zionist leaders gave us a definite promise that, if the Allies committed themselves to giving facilities for the establishment of a National Home for the Jews in Palestine, they would do their best to rally to the Allied cause.16

However, the dates here are important. Europa suggests that after the Balfour Declaration Jews went about planning to get the United States to enter the war, but the Balfour Declaration was made on November 2, 1917, seven months after the US had entered the war on the side of the Allies.

Even if we extend this back to when negotiations for the declaration began with the first meetings between Zionist and British officials, this was February 1917. By this point, America’s entry into WW1 was seen as a virtual inevitability, not least by the Germans, who switched to unrestricted submarine warfare on February 1st — just a couple of weeks after sending the Zimmermann telegram promising Mexico support if it invaded the US. Of course, Europa does not mention this telegram, the submarine warfare on American ships, or events like the sinking of the Lusitania in turning American public opinion. By the time the discussions that would lead to the Balfour Declaration were beginning, American public and elite opinion was already resigned to war. In “The Path To War”, the historian Michael Neiberg summarised this national mood:

By March 1917 they had reached a remarkable degree of consensus on a few fundamental points. First, they recognized that although the war in Europe was horrific, they felt that they had no choice but to enter it to secure Europe’s future, and their own as well. Europe may have been over there, but it was also close to home. During the course of three years, the two had become more connected as the safety once provided by the Atlantic Ocean vanished. Second, they collectively believed that they themselves had had little role in starting the war, hence they were acting in self-defense and in the wider interests of mankind against a German imperial government that had, in Wilson’s words, gone “mad dog.” Third, they agreed that their disparate ethnic identities meant less than their common identity as Americans. The war galvanized assimilation as nothing had done before.17

Even setting aside the awkwardness of making these dates work, there just isn’t evidence to show that Zionist lobbying played much of a role in US decision making at this time. While it’s true Zionist Jews supported American entry on the side of the Allied powers, Zionist power in America was not what it is today, and Jews in America were actually more divided on this than elite WASPs.

Internationalist Jews, many of whom were descendants of exiles from Russia, held such great enmity to the Russian Empire that they mostly opposed the US joining their side. And in the early 20th Century, it was these internationalist Jews who had disproportionate power in the United States. Ron Unz has a detailed breakdown of claims about the Balfour Declaration dragging the United States into the war which I recommend. He concludes that:

American Jews were overwhelmingly opposed to such military involvement and only a small fraction of them supported Zionism, being far outnumbered by anti-Zionist Jews, an imbalance that was especially pronounced among the wealthier, more influential Jews who played an important role in politics.18

It makes intuitive sense that the Balfour Declaration might have led to Zionist lobbying within the US to drag America into the war, but the evidence is just too thin to support such a conclusion. The majority WASP elite was very sympathetic to the Allied Powers from the beginning of the war and this was expressed in media and the behaviour of American financial institutions. Wall Street firms loaned huge sums of money to the Allies. This was dominated by WASP-led firms, and none lent more than J. P. Morgan.

In fact, Jacob Schiff’s Kuhn, Loeb & Company stood out among Wall Street firms for its commitment to neutrality and refusal to lend to the Allies. This was due to Schiff’s characteristically Jewish hatred of Tsarist Russia. Schiff argued that:

Though deplorable, German atrocities in Belgium, which attracted so much condemnation in Western Europe and the United States, were far less appalling than the brutal Russian persecution of the Jewish population of western Russia and Poland.19

Adam Tooze, in his monumental book on WW1 Deluge, describes how the Allies had become so indebted to American financial institutions that an Allied defeat and default would have meant economic devastation for the US.20 American industry also received a much needed boom from producing munitions for the Allies, and large sections of the American elites were pushing for war by the time of US entry. World War one actually represented a transition which “marked the end of the Rothschilds’ supremacy in government loans”, a decline that: “above all, was due to their weak presence in the United States where the sinews of war would henceforth be located.”21

Zionists like Bernard Baruch, Paul Warburg and Jacob Schiff pressured America to join WW1 (1:17:17)

While Baruch was made chair of the War Industries Board and represented the US at the Paris Peace Conference,22 none of these three were great lobbyists for American entry into the war, and two were actually notable for their lack of support for American intervention.

As mentioned above, Schiff stood out on Wall Street for his refusal to aid the Allies, and downplaying German crimes relative to the horrors of Tsarist Russia. Schiff and Warburg were two of the greatest lobbyists for neutrality among America’s financial elite:

Even more fervent than the support which Jacob Schiff and the Warburg brothers gave to a compromise peace was their hope that the United States would not be forced to intervene against Germany … Paul Warburg’s only complaint was that American treatment of Germany was insufficiently conciliatory.23

Warburg actually lobbied for some concessions to avoid war with Germany, such as banning travel by Americans on ships of belligerent nations, justifying German U-boat policy as just retaliation for the British blockade. And, in a detail that is very inconvenient for the Europa narrative, Warburg while serving as one of the original members of the Federal Reserve Board “led the board in its refusal after August 1914 to allow banks to rediscount bills of exchange from munitions purchases” because “Warburg claimed that this contravened US neutrality.”24

British airplanes dropped leaflets over Germany promising Jews a homeland in Palestine after the war (1:17:33)

This is true. The British Department of Information dropped leaflets to Jews in German, Austrian, and Russia territory which announced “The Allies are giving the Land of Israel to the people of Israel.”25

After the Balfour Declaration, the Jewish media began to display dehumanising anti-German propaganda to win American support for intervention (1:18:50)

Once again, the dates are just wrong. The United States entered WW1 officially on April 4, 1917. The Balfour Declaration came on November 2.

Herwig, Holger H. "Strategic uncertainties of a nation-state: Prussia-Germany, 1871–1918." The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States, and War (1994): 251.

Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918. A&C Black, 2014. Pg. 21

Fischer, Fritz. Germany's Aims in the First World War. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1967. Pg. 34.

IBID, Pg. 117

Nelson, Robert L. “THE BALTICS AS COLONIAL PLAYGROUND: GERMANY IN THE EAST, 1914-1918.” Journal of Baltic Studies 42, no. 1 (2011): 9–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43213000.

Nelson, Robert L. “From Manitoba to the Memel: Max Sering, Inner Colonization and the German East.” Social History 35, no. 4 (2010): 439–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41060788.

Fischer, Fritz. Germany's Aims in the First World War. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1967 Pg. 164

https://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/pdf/eng/1006_German%20Peace%20Offer_193.pdf

Gatzke, Hans W. Germany's Drive to the West (Drang Nach Westen): A Study of Germany's Western War Aims During the First World War. JHU Press, 2019.

IBID

Fischer, Fritz. Germany's Aims in the First World War. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1967. Pg. 296.

Kramer, Alan. "Naval Blockade (of Germany)." DANIEL, Ute, GATRELL, Peter, JANZ, Oliver, JONES, Heather, KEENE, Jennifer, KRAMER, Alan y Bill NASSON-editores (1914).

Broadberry, Stephen, and Mark Harrison. "World War I: Why the Allies Won." The Economics of the Great War. A Centennial Perspective (2018): 77-83.

Ferguson, Niall. The Pity of War: Explaining World War I. New York: Basic Books, 1999. Pg. 248.

IBID. 282.

Friedman, Isaiah. The Question of Palestine: British-Jewish-Arab Relations 1914–1918. New York: Shocken Books, 1973. Pg. 265.

Neiberg, Michael S. The path to war: how the First World War created modern America. Oxford University Press, 2016. Pg. 235.

https://www.unz.com/runz/the-balfour-declaration-and-116000-american-lives/

Roberts, Priscilla M. "A conflict of loyalties: Kuhn, Loeb and Company and the First World War, 1914–1917." Studies in the American Jewish Experience II (1984): 1-31.

Tooze, Adam. The deluge: the Great War, America and the remaking of the global order, 1916-1931. Penguin, 2014.

Cassis, Youssef. Capitals of capital: the rise and fall of international financial centres 1780-2009. Cambridge University Press, 2010. Pg. 148

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/baruch-bernard-mannes/

Roberts, Priscilla M. "A conflict of loyalties: Kuhn, Loeb and Company and the First World War, 1914–1917." Studies in the American Jewish Experience II (1984): 1-31.

Craig, Douglas. Progressives at War-William G. McAdoo and Newton D. Baker, 1863-1941. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013. Pg. 135

Judis, John B. Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the origins of the Arab/Israeli conflict. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014.

Thanks for doing this

"there is no doubt Germany deserves a good portion of blame for its decision to give Austria-Hungary a “blank cheque” to respond to Serbia in July 1914. A big part of this calculation was the belief among German leadership that there was a closing window where it could challenge the French-Russian alliance before Russia’s industrialisation made them unchallengeable."

That's nonsense. Germany was tricked into this war by Russia, France and Britain. Germany didn't want war with Russia, but Russia very much wanted war with Germany and Austria.