It has become a common trend for left-wing academics to leverage their status as “experts” in attempts to convince the public of seemingly counterintuitive claims about history. The establishment media is all too happy to promote these claims, which happen to be quite useful in normalising multiculturalism and pluralism to the masses. Among these is the case of “Cheddar Man”: a discovery of human remains dating from the 9th Millennium BC in Britain which purports to prove that the original inhabitants of the land were dark-skinned, thereby apparently negating any claim to the land that native Britons, as we have conceived of them until now, might have.

In the field of nationalism studies, there has been an equally fierce politicisation and attempt by left-wing, often Marxist scholars, to upturn what we think we know about the history of nationalism and ethnicity. Popular scholars in the field, especially of the so-called modernist school, commonly insist on the “newness” of nationalism. Following scholars like Ernest Gellner and Eric Hobbsbawm, one inevitably encounters the argument that nationalism was birthed in the late 18th Century or beyond. Before that, they assure us, the only identities that mattered to people were religious or local identities, like what town or parish they belonged to. Ethnic affinity, the relation between blood ties and nationalism, is left out of this picture.

Modernist scholars will point to multicultural Empires like the Roman Empire to demonstrate that national identity was non-existent in the ancient period. For left-wing historians too, the Roman Empire is a wellspring of examples of multiculturalism as the natural state of Europe. Popular historians like Mary Beard present Roman Britain as a diverse, multicultural place where people gave little thought to racial differences – a state-of-affairs that naturally existed before the invention of nationalism.

Is this true? Against modernists, I believe it can be shown that for most multicultural empires of the past, ethnicity was central to their self-conception and interaction with other groups. While it would be a mistake to claim that some of these examples were “nationalist” in the sense we understand it today, there exists compelling evidence that ethnicity and tribal kinship were central to them. Although they existed in a time before the modern nation-state and the accompanying academic nomenclature of nationalism, it is still possible to identify national identities within these empires, sometimes waxing and waning depending on circumstance. I also believe it can be shown that these kinship loyalties were naturally felt among the ordinary folk, and not an elite creation or false consciousness as modernist theorists have argued under the influence of Marxism. If we accept the basic insight of sociobiology – that humans as biological organisms tend to behave in ways that benefit their genetic relatives – it would be very surprising to look back on history and not see ethnocentrism informing politics to a great degree. So let’s look at Roman history specifically, and what it tells us about the interrelation of ethnicity and politics.

Prior to the expansion of the Roman Empire, the Italian peninsula was home to over thirty Italic ethnic groups, as well as Etruscans, Celts and Greeks, who were organised mostly into cities and city-states. Conflict between these groups was common, but larger ethnic identities were evident when they coalesced to deal with outside threats, as did the Greek city-states when faced with the threat of a Persian invader. The various Latin city-states shared a language and culture with the Romans, and were forced into closer cooperation when dealing with invasions from various other groups including the Celts and Etruscans between the 6th and 4th Centuries BC, forming the Latin League.

In 338 BC, Rome conquered the rest of the Latin League. Rome’s treatment of these states was quite benign: peace treaties were negotiated which did not impose harsh penalties on the defeated, and citizenship was generously extended. The city of Lanuvium had multiple conflicts with Rome, but when the Romans finally conquered it, Livy recounts that they "received the full citizenship and the restitution of her sacred things, with the proviso that the temple and grove of Juno Sospita should belong in common to the Roman people and the citizens living at Lanuvium"1

For a time, the only temple to Juno was in Lanuvium, and Roman pontiffs traveled there annually to offer sacrifices. This was a source of prestige for Lanuvium, and strengthened the sense of a shared identity between the people of Rome and Lanuvium with a focus on their shared gods. Rome had a number of traditions and mythology related to their descent from the mix of Romans and Sabines. This tradition of mixed origin for a single ethnic group – similar to the English sense of descent from Anglos and Saxons – helped the Romans normalise their policy of incorporating new tribes and spreading cultural Latinization.

Many have noted that one of the reasons for Rome’s success (as opposed to, say, Greek city-states) was its readiness in granting citizenship to conquered peoples. The constant growth in citizenry made it a force that smaller states could not withstand, and by its later period it was one of the most open empires, extensively granting full citizenship rights. But modern historians often over-focus on this eventual practice in later stages of the empire, and ignore how this process unfolded over centuries; for a long period, citizenship eligibility was limited to other peoples in the Italian peninsula in a kind of Italian proto-nationalism. In these early stages of Roman expansion, central Italy was gradually Romanised in a process of assimilation.

Writing in 1776 (before nationalism had even been conceived, according to some modernist scholars), Edward Gibbon wrote:

Till the privileges of Romans had been progressively extended to all the inhabitants of the empire, an important distinction was preserved between Italy and the provinces. The former was esteemed the centre of public unity, and the firm basis of the constitution. Italy claimed the birth, or at least the residence, of the emperors and the senate. The estates of the Italians were exempt from taxes, their persons from the arbitrary jurisdiction of governors. Their municipal corporations, formed after the perfect model of the capital, were intrusted, under the immediate eye of the supreme power, with the execution of the laws. From the foot of the Alps to the extremity of Calabria, all the natives of Italy were born citizens of Rome. Their partial distinctions were obliterated, and they insensibly coalesced into one great nation, united by language, manners, and civil institutions, and equal to the weight of a powerful empire.2

The Roman writer Vitruvius also identified a common Italian ethnicity when he wrote On Architecture, an exploration of the differences between Roman and Greek architectural styles. Vitruvius theorised how climate shaped the nature of different peoples in the Mediterranean, and that these group traits, in turn, manifested unique architectural styles. Vitruvius believed that the Italians, like the Romans, were a distinct people group which could be identified as having unique characteristics to the rest of the world – an ethnic group. Unsurprisingly, Vitruvius concludes that Italy was so ideally placed in the middle of the earth as to be divinely ordained.

The descent groups of Italy are the most perfectly constituted in both respects: in bodily form and in mental activity to correspond to their courage. Exactly as the planet Jupiter is itself temperate, its course lying midway between Mars, which is very hot, and Saturn, which is very cold, so Italy, lying between the north and the south, is a combination of what is found on each side, and her preeminence is well regulated and indisputable.3

Interestingly, Vitruvius uses Roman and Italian interchangeably in the writing, having grown up in a time when Roman citizenship was granted across the Italian peninsula, backing up Gibbon’s contention of the existence of an Italian national identity which formed within the Roman Empire.

Modern scholar Gary D. Farney also writes of a nationalising process occurring within Italy under Rome. He notes that the Romanisation process within Italy was not simply a one way spread of Roman customs and citizenship, but an exchange of culture and the development of a shared Italian culture.

In the first centuries of the Roman Empire, the various ethnic groups that made up Italy coalesced into one singular Italian identity. These groups lost some of their peculiar Italic identity, like their languages, their unique nomenclature, aspects of their religion and their unique reputations. Yet, some of the same aspects of their culture became considered Roman and Italian rather than just the practices of one Italian group.4

This level of cultural hybridisation was never replicated with groups like those of Asia Minor, though Rome adopted and Latinised some of their cults and mythology. By the third century AD, when the Empire had spread across the Mediterranean world and admitted hundreds of different peoples, being Italian was still considered the ‘best’ ethnicity. From the 1st to the 3rd centuries AD the vast majority of senators were Italian or descendents of Italian colonists in the western provinces, and Farney notes that both senators and emperors were keen to prove ancestral connection to Italy. The historian Ronald Syme documented how many Emperors of the 3rd century went to great lengths to prove their descent could be traced to the area of Etruria in central Italy.5

If there was a sense of national identity within the Roman Empire, is it not strange that the writers of the time did not seem to identify it? Modernist theorists would certainly point to the absence of a conscious national identity in pre-modern writers as evidence of these being recent constructions, but this isn’t necessarily the case. Though ancient writers may not have used the terminology we are familiar with around discussions of nationalism and ethnicity, they testified to something we would intuitively call a nation: a people with a shared kinship and common culture and religious beliefs, living in a unified state governing their ancestral homelands. As shown by the example of Virtuvius, they were often clear about considering the Italian peoples a race distinct from the rest of the world, and had a clear understanding of the boundaries of this greater nation.

Roman National Identity and War

Azar Gat writes of how ethnic loyalties played a role in conflicts which divided the Roman Empire. Rome brought the Greek states to its south under its hegemony, only for them to enthusiastically ally with fellow Greek Pyrrhus of Epirus. A similar pattern is observed in Rome’s conflict with its greatest enemy, Hannibal of Carthage. Hannibal’s victory at Cannae, during the Second Punic War in 216 BC, succeeded in breaking up the Roman alliance, Greeks and other peoples of Southern Italy deserted Rome to seek their freedom under Hannibal, while the similarly separatist Celts and Etruscans in the north engaged in rebellion.

Only the Latins and other thoroughly Romanized communities of central Italy remained loyal to Rome (though, exhausted by the war, some of them eventually refused to contribute more troops to the war effort). Indisputably, Rome’s presence and deterrence by terror were strongest in its immediate vicinity; but the threat of Hannibal’s armies was no less potent…Ultimately, the communities of central Italy preferred a hegemon from their own ethnic stock to a foreign one.

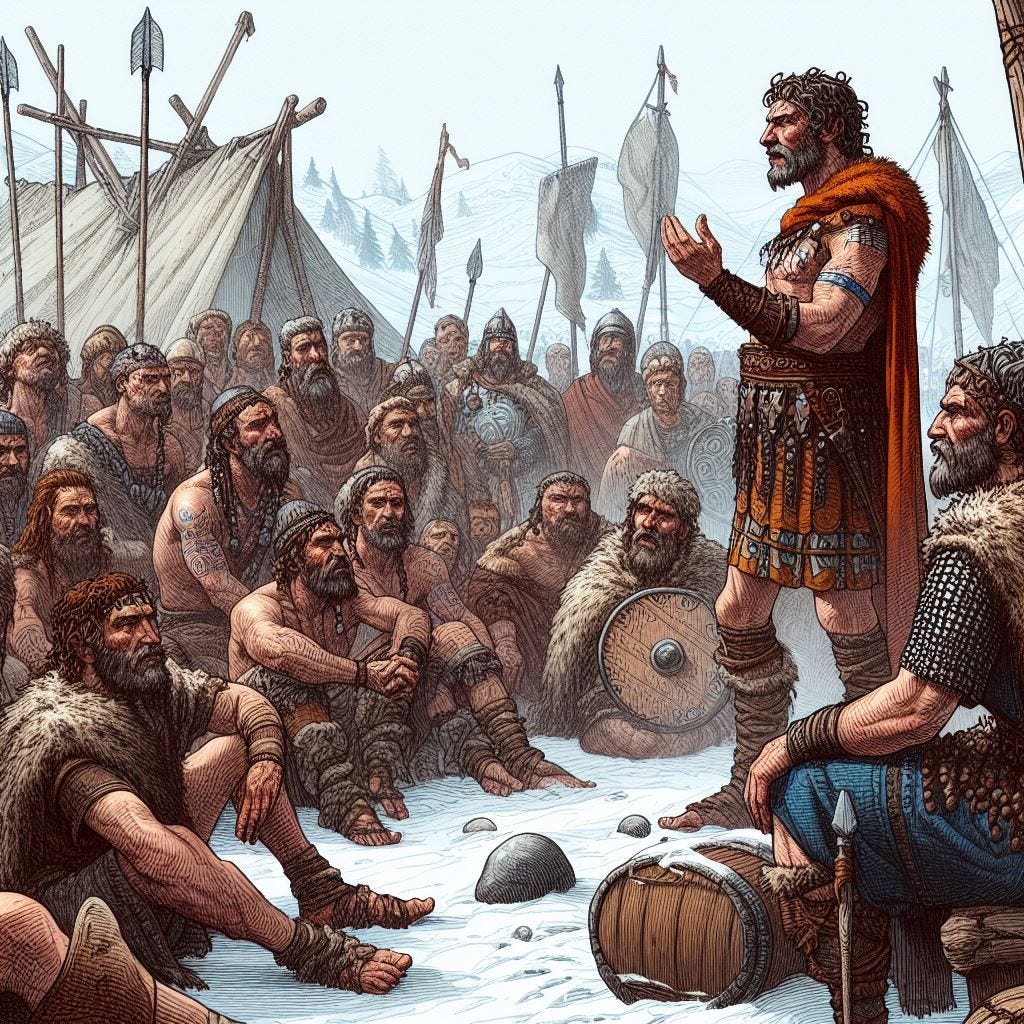

Hannibal evidently recognised the differences in loyalty to Rome among different peoples. During his invasion of northern Italy, he made a point of contrasting harsh treatment of captured Roman prisoners with the kindness shown to Celtic peoples who were fighting on the Roman side. At one point, Hannibal even made an appeal to the sovereignty of these peoples against the oppressive, Imperial Roman rule:

In his winter quarters he called an assembly of all his prisoners and spoke to them of the cruelty and faithlessness of the Romans, reassuring them that he hadn’t come to make war on them, only Rome. His motive, he claimed, was freedom for all people who had been abused for so long by the imperialism of the Roman state. Rome was like a cancer spreading across the Mediterranean, devouring nations and their ancient liberties in its hunger and greed. Carthage, on the other hand, had been trading with Italy for centuries and had never tried to conquer them. He did not claim that his motives were purely altruistic, for they wouldn’t have believed that. He clearly wanted to defeat Rome to benefit Carthage, but the Italians had every reason to help him—because it also benefited them.6

If ethnicity and national pride were not motivating factors in the ancient period, as it is fashionable to claim, it would be odd for Hannibal to make appeals like this, or expect the Celtic peoples within Rome to be less loyal than the Italians. Hannibal was correct, Celtic tribes did not need a lot of persuading to turn on Rome and join Hannibal. In contrast, the unwavering loyalty of the central-Italians to Rome went well beyond Hannibal’s expectations.

This remarkable loyalty is displayed by an example from the aftermath of the battle of Lake Trasimene, a crushing defeat for the Romans. Hannibal captured a contingent of Latins who had been fighting for Rome, promising their safety if they defected. Polybius quotes Hannibal as saying “he was not come to fight against Italians, but in behalf of Italians against Rome.”(Polyb. 3.85) And yet, no Latin ally defected to join Hannibal, nor did any other people of central Italy. Indeed, they continued to stand with their kin in Rome even when the war looked a lost cause, with Hannibal’s invading army appearing unstoppable.

The sense of impending doom in Rome at the time is hard to imagine. Hannibal’s routing of their army at Cannae, still regarded as one of the greatest military victories of all time, cost Rome and their allies almost 80,000 soldiers – a staggering number that represented about twenty percent of their military aged men. It was the worst of a series of great defeats to Hannibal which had depleted Rome not only of tens of thousands of soldiers, but many experienced leaders and military personnel, and encouraged multiple defections. Days after Cannae, an entire Roman army was destroyed by a Gallic army in Northern Italy. Roman historians report of a situation where the residents of Rome awaited the descent of Hannibal’s army on their city at any moment. The scale of the defeat at Cannae was so devastating that it pushed Roman leaders to desperate measures, such as sending a delegation to consult the oracle at Delphi and making human sacrifices to the gods.

The Romans took previously unthinkable measures to try and reverse their fortunes. This included allowing the recruitment to the army of all males over the age of seventeen, with some even younger being conscripted. This shattered some of the class barriers which existed in army recruitment: a prospective soldier previously had to have a minimum amount of land holdings to qualify. Rome’s quest for soldiers was so extreme that they released slaves to convert them to soldiers. Reading about this situation, one can imagine the mood in Rome being similar to Berlin in 1945, as the Germans desperately called up members of Hitler youth to try and fend off the unstoppable Red Army.

Yet the Roman Senate showed unflinching defiance, not even considering surrender. This seems like a pivotal moment in the emergence of a more conscious Roman nationalism. The unflinching loyalty of Romans and their Latin allies, even after years of crushing defeats and a seemingly hopeless military situation, would be difficult to explain if we accept the modernist view of nationalism as a modern, elite-constructed phenomenon, which held little sway over the ordinary masses throughout history. Far from patriotism being something reserved for the elites of Rome, the historian Adrian Goldsworthy writes that the extraordinary measures taken to replenish the army were only

made possible by the willingness of ordinary citizens to submit to years of harsh military discipline and extremely dangerous campaigning. It is vital to remember that all classes at Rome and amongst most of the allies felt very strong bonds of loyalty to each other and the State.

And, while some deserted, “the overwhelming majority did not and were led by fierce patriotism to sacrifice themselves for the State.”7

It was not as if they had reason to believe they faced certain death, or a worse fate, if they too defected or sued for peace with Hannibal. Hannibal held off on attacking Rome itself, hoping they would agree to negotiate their surrender. Livy wrote that Hannibal:

Was not carrying on a war of extermination with the Romans, but was contending for honour and empire. That his ancestors had yielded to the Roman valour; and that he was endeavouring that others might be obliged to yield, in their turn, to his good fortune and valour together.8

Hannibal persisted in trying to swing Latin states to defect to his side, as other groups in the south of Italy had. Coming out of an empire of city-states with restrictive citizenship requirements, Carthage secured its allies far more through coercion and violence than Rome had. Historians have remarked that he did not seem to recognise a difference in the mindset of the ever-loyal Central Italians and South Italians, some of whom had been at war with Rome on and off for centuries.

It seems Rome’s lighter touch with its defeated Italian enemies in previous centuries, its inclusive citizenship policies and the effects of Romanization had indeed forged an unbreakable Roman alliance. This central Italian block, with common rights and duties for all members, a common culture, shared language and intertwined religious practices now combined with a willingness to die for their nation, now emerges as a nation.9

As Rome did the unthinkable and turned the tide of the war against Carthage, a more hardened nationalism had emerged from their desperate struggle. Hannibal expected his invasion to shatter the Italian alliance system, and he was indeed successful in the North and South, but in Central Italy which contained Rome and closely related Latin groups, it made historical differences wane and catalysed the emergence of a broader Roman nationalism. The whole ordeal shows the importance of ethnic identity and a sense of common kinship in determining the attitudes of the masses and the formation of national states. It also shows that, contra many leftist historians, ethnicity and national pride was central to the Roman Empire, at least in its core of Central Italy, and eventually extending to all of Italy.

When Rome finally turned the tables on Hannibal and took the fight to Carthage’s native territory in North Africa, the same dynamic repeated itself wherein peoples on the periphery showed a swift willingness to defect to the invading force. Many peoples who had been subjugated by Carthage took the opportunity to defect to Rome, while the core of Phoenician city-states remained loyal to Carthage right to the point of complete military defeat.10

The defeat of Hannibal, after Rome’s near annihilation at his hands, led to an emergence of inspired Roman historians rushing to record complete histories of Rome. Quintus Fabius Pictor, the first Roman historian who was also appointed to travel to the Oracle of Delphi for guidance after the defeat at Cannae, began his work as a historian around the start of the second century. Quintus Ennius, considered the father of Roman poetry, wrote his epic poem The Annales in the same period. The Romans suddenly thought it important to record their history as a people, and explain the source of their superiority which had led to such military dominance. While there was a Roman national identity before the Second Punic War, Rome’s heroic defiance on the brink of annihilation seems to have solidified it and instilled a sense of supremacy.

It should now be clearer that, contra the modernist theory of nationalism, ethnicity and a sense of national identity and pride were powerful forces in the Roman Empire, forces which were strengthened during its darkest moment as it came close to annihilation at the hands of the Carthiginians. Neither the willingness of non-Italian peoples in the Italian peninsula to secede, nor the resolve of Rome’s Italian allies to fight with them can be explained without calling on the ethnocentrism and national sentiment of these peoples. Ancient writers of the time, and historians unbiased by the dogmas of the modern academy, clearly attest to an Italian national identity which came to exist within the Empire – an identity that remained important even as the Empire was at its most multicultural, with Emperors and Senators proudly appealing to their Italian heritage. Before the rise of Italy the nation-state, there existed Italy the nation, the proud heart of one of history’s greatest empires.

Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 8, Chapter 14

Gibbon, E. The history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire Vol. 1 Chapter II Part II

Vitruvius, On Architecture 6.1-12

Farney, G. D. (2011). Aspects of the emergence of Italian identity in the early Roman Empire. Communicating Identity in Italic Iron Age Communities, 221-230.

Syme, R. 1983. Emperors from Etruria. In Historia Augusta Papers, 189–208. Oxford.

Freeman, P. (2022). Hannibal: Rome's Greatest Enemy. Simon and Schuster. Pg. 55

Goldsworthy, A. (2012). The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146BC. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Pg 315-316

Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 22, Chapter 58

Roberts, T. (2014). The Roman nation: Rethinking ancient nationalism (Doctoral dissertation, University of Rhode Island). Pg. 109

Gat, A. (2012). Nations: The long history and deep roots of political ethnicity and nationalism. Cambridge University Press. Pg 77

The idea of nationalism being a new thing I have always felt is something that you could only really believe if you have really not read all that much from the past. When it comes to my country Norway, you find clear nationalistic tendencies in the some of the earliest sagas written in the middle ages after Norway's founding. It is clear that the nation is being lifted up and that there is a commonality between the people of the nation.

Great article, Keith. People love to forget that Roman citizenship wasn't extended outside of Italia until way later under Emperor Caracalla, which massively screwed up the empire for all time. Before Caracalla, only about 5 percent of the empire had citizenship. Kinda reminds me of the United States' switch to Jacksonian democracy in the 1820s.