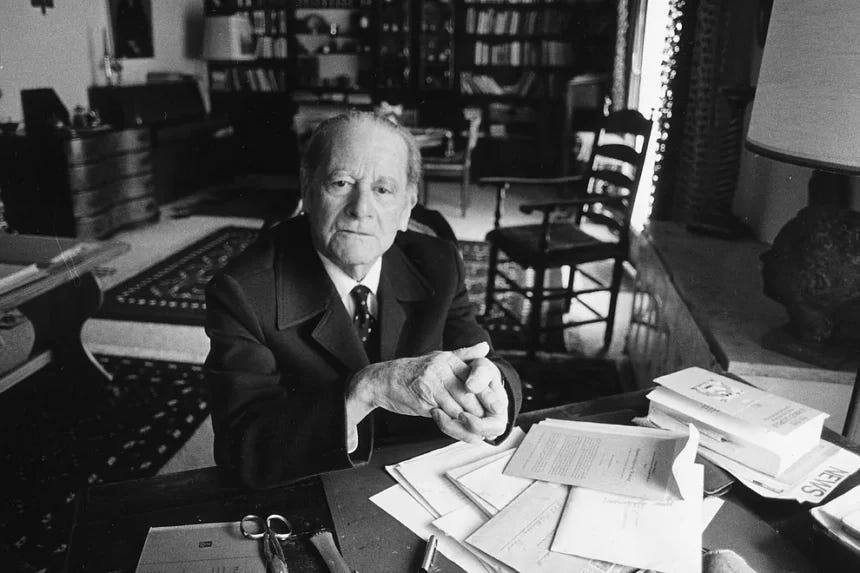

Carl Schmitt: Nihilist, Authoritarian, Democrat?

Grappling with the many tensions in Schmitt's political theory

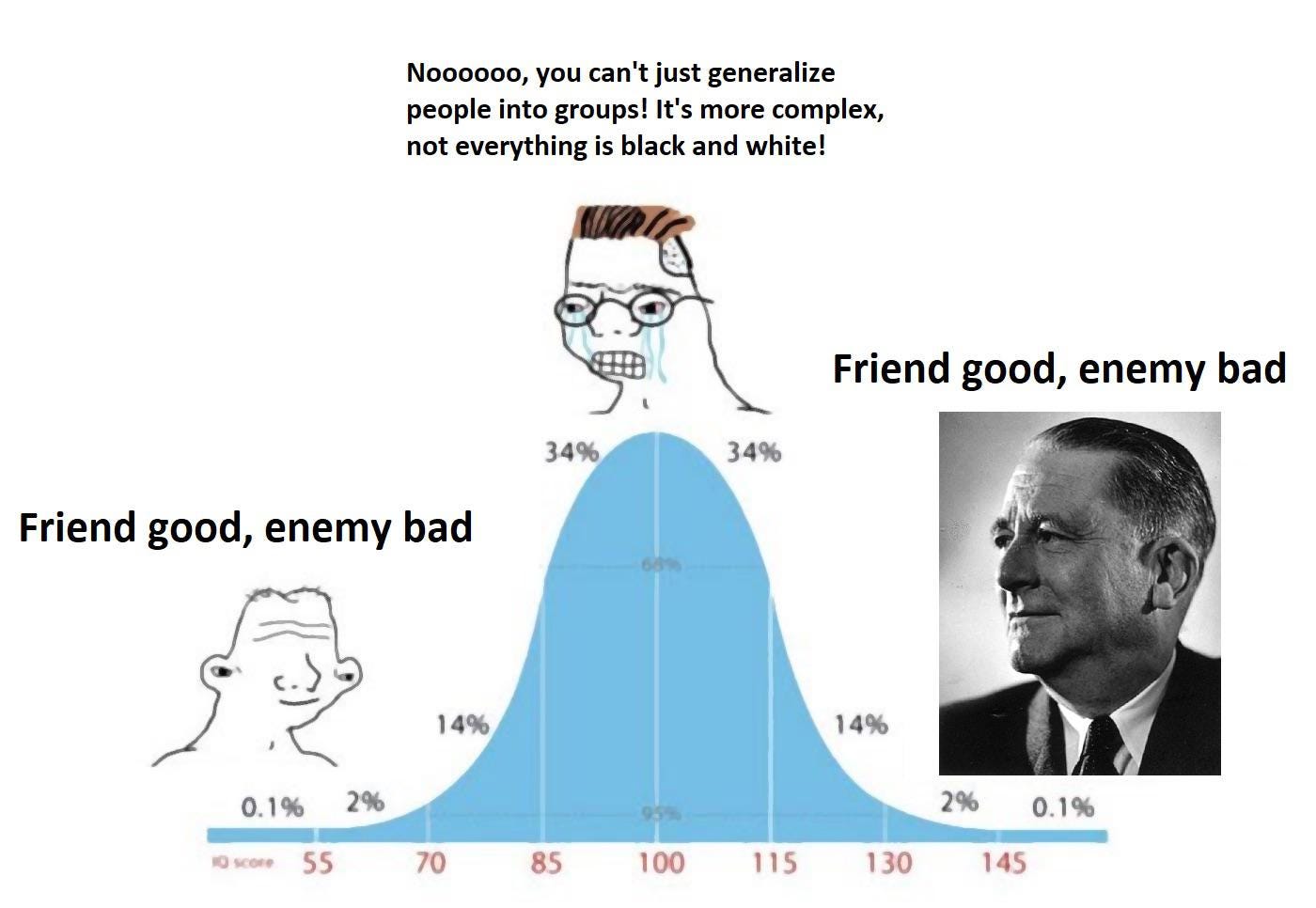

There are probably few political theorists who have been as systematically misread as Carl Schmitt. Perhaps this is the destiny of any thinker whose influence extends well beyond his academic field, but Schmitt's revival among the online right in recent years has produced especially crude appropriations. The Schmitt of the modern right has been reduced to a kind of patron saint of political tribalism, with his friend-enemy distinction taken to be a crude prescription to treat politics as an amoral zero-sum game where the only goal is to reward allies and punish opponents.

Ironically, many of Schmitt’s contemporary rightist fans have an understanding of his philosophy that aligns with Marxist theorist Franze Neumann's early portrayal of him as an advocate for "brute force" against the principles of democracy and the rule of law. Neumann’s Schmitt was an illogical thinker, much like Georges Sorel, whose political philosophy was a justification for the exercise of raw power over political adversaries to the point that "every opponent can become a foe subject to physical extermination.”1

Schmitt's political theory begins with a deceptively simple premise: politics possesses its own autonomous logic that cannot be reduced to morality, aesthetics, or economics. While each of these domains operates according to its own criteria, the political is to be defined by a criterion of intensity: the division of human beings into friends and enemies.

This makes politics a meta-category that parasitically draws energy from other domains of human experience. Religious, national, economic, or moral differences all become politicised when antagonism reaches a decisive intensity. The political possesses no essence of its own — its truth emerges only in the decisive moment when conflict becomes existential. As Schmitt writes:

The political can derive its energy from the most varied human endeavors, from the religious, economic, moral and other antitheses. It does not describe its own substance, but only the intensity of association or dissociation of human beings whose motives can be religious, national (in the ethnic or cultural sense), economic, or of another kind and can effect at different times different coalitions and separations.2

The stark clarity of Schmitt's friend-enemy distinction attracts both casual readers and critics who condemn it as nihilistic. By defining politics through conflict's intensity rather than moral or economic criteria, Schmitt appears to divorce politics from questions of good, justice, or truth, seemingly elevating enmity and decision as ends in themselves. Critics from the liberal left and traditional right have been able to seize on this apparent groundlessness of Schmitt’s theory. The most powerful expression of this critique came from Karl Löwith, an influential philosopher of history, who argued that Schmitt had created a "nihilistic vision" where politics would be reduced to mere struggle, devoid of teleological purpose.

Löwith’s Critique

Karl Löwith accuses Schmitt of being an “occasionalist.” Schmitt himself criticised 19th-century liberal “occasional romanticism,” where the individual replaced God as the ultimate authority, treating every passing event as a potential source of meaning without any fixed centre. Löwith argues that Schmitt merely reproduced this structure: instead of the isolated individual, he elevated the state (or sovereign decision-maker) to divine status as final authority, committing the same error in different form.

Because Schmitt’s decisionism has no substantive grounding in a teleological philosophy, it becomes entirely determined by immediate historical circumstances. This theological emptiness has profound implications for Schmitt's thought. While thinkers like Kierkegaard and Marx confronted chaos with decisions anchored in something substantial — God for Kierkegaard, humanity for Marx — Schmitt's sovereign stands on nothing but the contingency of the moment. There is no "highest court of appeal" beyond present circumstances; no moral or spiritual measure to guide decisions. The sovereign decides simply because the situation demands decision, not because any pre-existing law, principle, or truth commands obedience. As Löwith put it:

Hence it will remain to be asked: by faith in what is Schmitt's ‘demanding moral decision’ sustained, if he clearly has faith in neither the theology of the sixteenth century nor the metaphysics of the seventeenth century and least of all in the humanitarian morality of the eighteenth century, but instead has faith only in the power of decision?3

Schmitt draws on historical examples of religiously informed sovereigns, like Cromwell's puritanical absolutism, but these interest Schmitt only insofar as they are good demonstrations of the pure exercise of power. Their substantive ethical or theological commitments are irrelevant to his analysis.

This analysis reveals how fundamentally Schmitt's thought diverges from its apparent Christian or conservative affiliations. His theological references serve purely instrumental purposes, legitimizing authority in formal terms while imposing no substantive constraints. Schmitt's decisionism constitutes what Löwith calls "active nihilism": rather than merely lamenting the absence of moral and spiritual anchors, it actively thrives in the void their removal creates.

Theology Without Transcendence

Viewed through Löwith's lens, the theological elements in Schmitt's work become clearer. His sovereignty resembles nominalist theology's divine omnipotence: law and order emerge not through reason or natural discovery but through pure acts of will creating from nothing. Authority achieves legitimacy not by corresponding to higher norms but through sheer deciding power. What masquerades as "political theology" reveals itself as theology of power emptied of transcendence. For Schmitt, politics is not where ethical or spiritual values find application but where they face suspension, replaced by decision's and enmity's raw intensity.

Schmitt's nihilism is not simply an empty void. It is an active force that elevates decision and enmity into the highest political realities. Politics, for Schmitt, cannot be reduced to administration, law, or moral striving. It is an arena where the fundamental antagonisms of human existence are confronted without mediation. The sovereign does not restore order to chaos by appealing to truth or justice. The sovereign actually reveals that no such anchor exists, and in its absence, decision itself becomes the only measure.

This places Schmitt in a curious proximity to Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes too rejected transcendent or natural sources of political normativity and sought instead to ground order in a self-sustaining mechanism: the fear of death and the rational laws of preservation that flowed from it. For Hobbes, sovereignty emerges not from divine command but from life-preservation necessities under conditions of perpetual conflict.

Schmitt’s work could be seen as a similar attempt at a mechanistic substitution for a teleologically grounded political philosophy, though his is arguably much more radical. Hobbes still sought some minimal universality — the universal fear of violent death, which could serve as the foundation of a stable order. Schmitt refuses even this. For him, there is no shared human passion or universal drive toward peace that could underwrite political authority. There is only the intractable division between friend and enemy, which no mechanism of preservation can ultimately overcome. So while both thinkers replace transcendence with an immanent “law of motion,” in Schmitt’s worldview the rational pursuit of peace takes a backseat to the reality of the permanent possibility of conflict.

Carl Schmitt, Democrat

Löwith’s critique of Schmitt's decisionism as a justification for the amoral exercise of power or rootless "occasionalism" was popular among liberal critics of Schmitt post-War, especially after his support for Germany’s National Socialist regime seemed to confirm his thought ended in support for the worst excesses of tyranny. Richard Wolin articulates what became a standard critique of Schmitt when he writes:

The emphasis on the exception to the exclusion of all normativism, proceduralism, and institutional checks allows him to degenerate into an advocate of charismatic despotism.4

But there is an important point many of these criticisms of Schmitt miss, which is that his theory of the political is always anchored in a society's collective values, what he terms the "people's sense of right." Sovereign decisions prove effective only by crystallising a community's pre-political orientations into political form, enforcing boundaries of collective identity that already possess moral and spiritual coherence:

If order in the modern world, for Schmitt, is based on the continuing existence of a state, this is not so much because the state embodies power rather than truth, but because the state establishes a specific perspective on morality and metaphysics, which is then formalized and institutionalized in a set of norms once the sovereign has made the decision for a particular understanding of order.5

This insight transforms our understanding of the state of exception. When sovereigns suspend law, they act not from self-interest or mere power politics but to preserve the specific values and moral ideals their state embodies. This symbolic dimension proves crucial for understanding why simplistic right-wing appropriations of Schmitt fail: without it, conflicts never transcend biological survival to become genuinely political oppositions. Ideological and ethical distinctions serve as preconditions for political conflict's emergence.

Schmitt insists that politics cannot be reduced to morality or economics, yet he equally denies that politics can be wholly detached from them. The friend-enemy distinction does not arise in a vacuum but emerges from concrete collective differences, typically differences in national character, that have already been experienced as meaningful divisions by a people. The state of exception thus becomes a space where rival visions of the good clash, each seeking to define public order. Sovereign decision resolves this competition by determining which conception prevails, creating a "point of ascription" from which all subsequent norms flow.

Schmitt’s sovereignty emerges from conflicts over competing visions of the public good, which he sees as the root of political antagonism. In Political Theology, he writes:

Whenever antagonisms appear within a state, every party wants the general good—therein resides after all the bellum omnium contra omnes.6

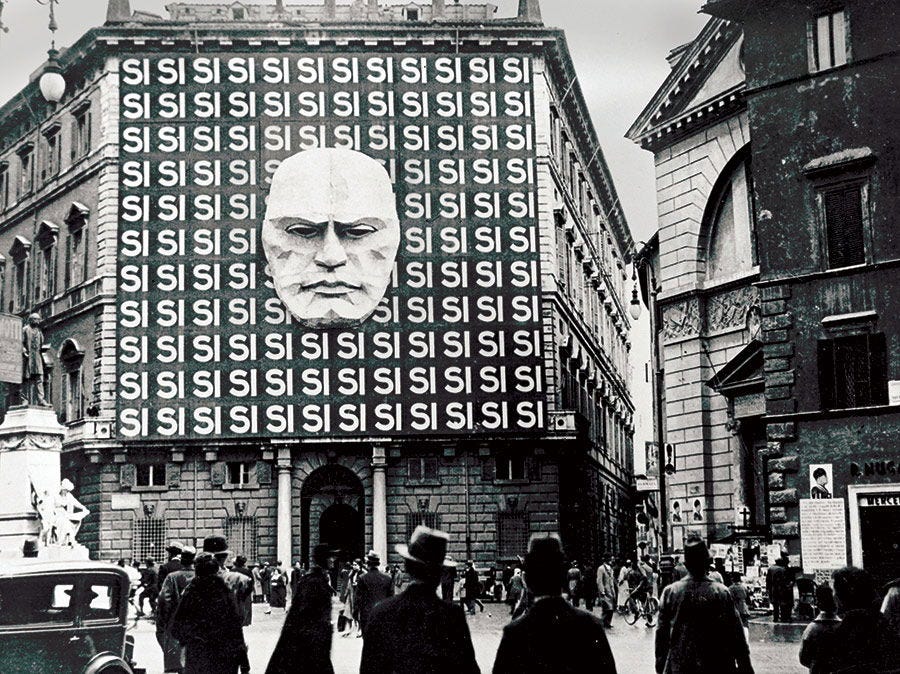

The sovereign’s decision in a state of exception is not a grab for personal rule or a vendetta against enemies but a resolution crystallising one vision as the community's identity. Far from advocating tyranny, Schmitt is a profoundly democratic thinker, defining democracy as the “identity of ruler and ruled” — a definition he adapted from Rousseau. In The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy, he critiques liberalism’s vulnerability to minority capture, arguing that authentic democracy requires a sovereign aligned with the people's unified will, capable of transcending positive law to ensure collective self-determination. Such decisions, effective only with popular support, embody popular sovereignty as communal self-government's ultimate expression.

While the sovereign’s decision in the state of exception is decisive, there must be a certain minimum of popular support for the sovereign’s decision, and there must be an identity between his people along the identity expressed in the friend-enemy distinction set by him. Schmitt seems to suggest that a successful sovereign decision on the exception would be the ultimate case of collective self-government.

The sovereign decision…is the only form in which popular sovereignty can be actualized, and popular sovereignty, Schmitt argues, is the only modern basis for the legitimacy of law.7

This defence of genuine popular sovereignty overriding the proceduralism of liberal order and its negotiated pluralism, makes Schmitt’s theory a defence of homogeneity as a prerequisite to genuine democracy. He emphasises shared identity as essential for legal determinacy and non-arbitrary governance. In homogeneous societies, laws remain uncontroversial because the general will appears obvious. Exceptional decisions ensure this system's smooth operation by excluding minoritarian dissenters.

This for Schmitt is true democracy: for a people to maintain self-determination, they need the power to continually expunge corrupted law designed to undermine unity of will. Liberal pluralism, which today identifies itself with “the rule of law” and “democratic values”, is fundamentally anti-democratic because it is designed to perpetually thwart the majority will. Legal safeguards, minority lobbying, parliamentary coalitions, and universal human rights — the entire liberal pluralist apparatus — systematically frustrates the free exercise of the general will to protect minority interests. Far from coming up with post-hoc justifications for tyranny, Schmitt takes himself to be defending democracy by highlighting conditions for a political community's preservation.

Schmitt’s reliance on a people’s “sense of right” shifts legitimacy from universal principles to historically contingent collective identities, yet this does not fully escape the charge of nihilism brought against him by critics. Without natural law or moral universals to adjudicate competing values, each community’s horizon remains irreducibly particular, making inter-communal conflict the politicals defining essence. Though Schmitt was a Catholic, his thought is “realist” in that it pursues an autonomous interpretative framework that eschews transcendence in favour of the autonomy of the political. Löwith was fundamentally correct that this move is a radical departure from the tradition of Christian political thought, which always sought to subordinate earthly authority to divine command and universal moral law.

Yet Schmitt’s thought cannot escape the reality that politics feeds on deep-seated commitments. His theory thus hovers in an unstable space: insisting on the radical autonomy of the political while tacitly acknowledging its dependence on pre-political values that make the friend-enemy distinction intelligible. This fundamental tension explains both Schmitt's enduring intellectual appeal and the ease with which ideologues misappropriate his work for their own purposes.

Neumann, Franze. Behemoth: the structure and practice of national socialism, 1933-1944.

Schmitt, Carl. The concept of the political. Pg. 38.

Löwith, Karl. Martin Heidegger and European Nihilism. Columbia University Press, 1995.

Wolin, Richard. “Carl Schmitt, Political Existentialism, and the Total State,” Theory and Society 19, no. 4 (August 1990): 399.

Pan, David. "Carl Schmitt on culture and violence in the political decision." telos 142, no. 142 (2008): Pg. 64

Schmitt, Carl. Political Theology, Pg. 9

Vinx, Lars. "Carl Schmitt's Defense of Sovereignty." (2015).