Is wokeism merely a response to modern issues like racial justice and trans rights, or is it the reincarnation of an ancient Christian heresy? You might assume the former. But in the conservative intellectual world, the latter has become something like an orthodoxy. The claim that “wokeism is gnosticism” has become a minor intellectual industry among post-liberals, reactionaries, and Catholic traditionalists that has a small library of books and essays in recent years.

Gnosticism was the original woke culture, says OnePeterFive, a Catholic journal; Bishop Robert Barron writes on gnosticism as the philosophical roots of wokeism for the Acton Institute; Wokeism is the new face of an old heresy, explains Thomist philosopher Edward Feser; according to anti-woke crusader James Lindsay, “a thread of Gnostic cult belief that has shaped every facet of the West for at least the last three hundred years”; Wokeism is the Gnostic religion of the intellectuals, writes a contributor to Chronicles Magazine; and Wokeness is grounded in a Gnostic understanding of the world, writes a contributor to National Affairs.

This kind of thing isn’t actually anything new to conservatives, either. In a 1957 edition of The National Review, a Catholic scholar named Frederick Wilhelmsen complained that Gnosticism had “worked its poison into the blood of our body politic.” Wilhelmsen’s examples? For one, President Eisenhower’s refusal to support the Hungarian uprising in 1956. This could only be understood by recognising Ike’s “Gnostic mist”, a decision informed by “Gnostic illusions about the future.”

In 1962, another National Review alumni named Brent Bozell told a crowd of 18,000 conservatives at Madison Square Garden that communism and liberalism had the same root — “the ancient heresy of gnosticism with its belief that the salvation of man and society can be accomplished on this earth.” Bozell warned the packed crowd that in their gnostic quest liberals were now becoming sympathetic to the Soviet ideal of remaking man, and so “if gnosticism is ever to triumph, it will triumph in the communist form.”

Conservative thinkers invoking gnosticism to explain their enemies’ motives owe a lot to Eric Voegelin, who blamed Gnosticism for the rise of every modern ideological movement from communism and fascism, to psychoanalysis and liberal progressivism. Voegelin saw the Gnostic impulse as a rejection of the world in favor of a purified order — what he famously called “immanentizing the eschaton,” or attempting to usher in heaven on earth. These movements were called “gnostic” simply for being utopian and intellectual — as if those traits were unique to gnosticism, and despite the fact that actual gnostic texts are strikingly apolitical and anti-utopian.

Yet there is obviously something still very appealing about this kind of argument to conservatives, and it has seen a recent revival as their intellectuals grapple with the rise of the newest iteration of progressive utopian thinking in the form of wokeism. In The Gnostic heresy’s political successors, Edward Feser argues that the first feature of the gnostic mentality is that:

It sees evil as all-pervasive and nearly omnipotent, absolutely permeating the established order of things.

This differs from Orthodox Christianity, which teaches that creation is fundamentally good, and from this follows the concept of natural law. By contrast, wokeism, according to Feser, sees the world as pervaded by evil — not in metaphysical terms, but in the form of systemic racism:

For CRT, the all-pervasive and near omnipotent source of evil in the world is the “racist power” of “white supremacy,” “white privilege,” and indeed “whiteness” itself. This racism is “systemic” in a Foucaldian sense – it percolates down, in capillary fashion, into every nook and cranny of society and the unconscious assumptions of every citizen. It is especially manifest in all “inequities,” which result from the “implicit biases” lurking even in people who think of themselves as free of racism.

This is the basic argument of all the “wokeness is gnostic” people: gnostics looked at the world and saw nothing but evil, woke people look at the world and see nothing but inequality and injustice.

Gnosticism isn’t easy to define, because it wasn’t one movement but a collection of early religious movements that shared a belief that the material world was illusory and fallen, a kind of cosmic mistake. Gnostics typically believed the physical world was the product of a flawed or evil lesser god — the Demiurge — and that it separated us from our natural end — the union of our own divine nature with the real hidden God who transcended nature. Gnostics believed the overcoming of the physical and the awakening of our divine spark could not come through faith or action but only through a transformation of the self through secret knowledge — gnosis. In this sense, it was more similar to the ascetic, acosmist spiritual movements of the East than what we associate with Western philosophy.

All this is to say that if anything defined the gnostic outlook, it was a complete repudiation of the material world and its temptations, turning instead to asceticism and the spiritual life (of course, this has at times manifested in some decidedly “left-hand” libertine approaches that were anything but ascetic). What they emphatically were not, however, was political utopians. Temporal injustices like a dearth of Black CEO’s actually becomes less of a concern when your concern is escaping this fleshy prison altogether. This kind of political utopianism originates from a much more materialist disposition. After all, the furore of Marxist utopianism came from a thinker who presented a wholly materialist interpretation of history and vision of utopia.

In fact, if the apostles of woke have a metaphysical disposition at all, it’s much more optimistic than Feser et. al portray. Far from rejecting the material world, the woke think we can create a worldly paradise if only we can extirpate inequality and discrimination. Conservatives will say something like “the woke think white people are born inherently evil or racist”, but this isn’t really the case.

One thing the woke absolutely take for granted — the whole basis for their political outlook — is that we enter the world as blank slates, and systems of power reproduce inequalities and discriminatory attitudes. They are only so motivated to undo these power systems because they believe the world of true egalitarianism where these structures have been done away with would be so beautiful. There is no ascetic or spiritualist impulse here. Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart goes as far as to say — and I agree with him — that:

If I were pressed to give an account of the causes that allowed secular modernity to evolve out of early modern Christendom, one formulation I would be tempted to venture—in order to be provocative, admittedly, but also quite in earnest—is that modernity at its most truly nihilistic is in very great part the effect of the final expulsion of any genuinely gnostic spiritual disquiet from the consciousness of the Christian West.

And if the woke disposition was another case of the gnostic rejection of materiality, wouldn’t we expect to find among their leaders a few gnostics? But far from being esotericists or world-denying Valentinians, any survey shows most are either atheists with an unquestioned belief in the good of a post-Christian ideal of equality and the universal dignity of man, or themselves Christians in quite the opposite mold of the gnostic. When they are religious they tend to come disproportionately from Evangelical Christianity, which is about as far away as you can get in a Christian context from gnostic esotericism. Cornel West is Professor of Philosophy and Christian Practice at the Christian Union Theological Seminary. Jemar Tisby, author of woke bestsellers The Color of Compromise and How To Fight Racism is also an evangelical Christian who received his academic credentials from the Reformed Theological Seminary. On the atheist side, Ibram X Kendi, the author of How to be an Antiracist, thinks Jesus was a political revolutionary and that “trying to “save” souls is “racist theology” which only “breeds bigotry.” Not a very gnostic outlook.

Transhumanism

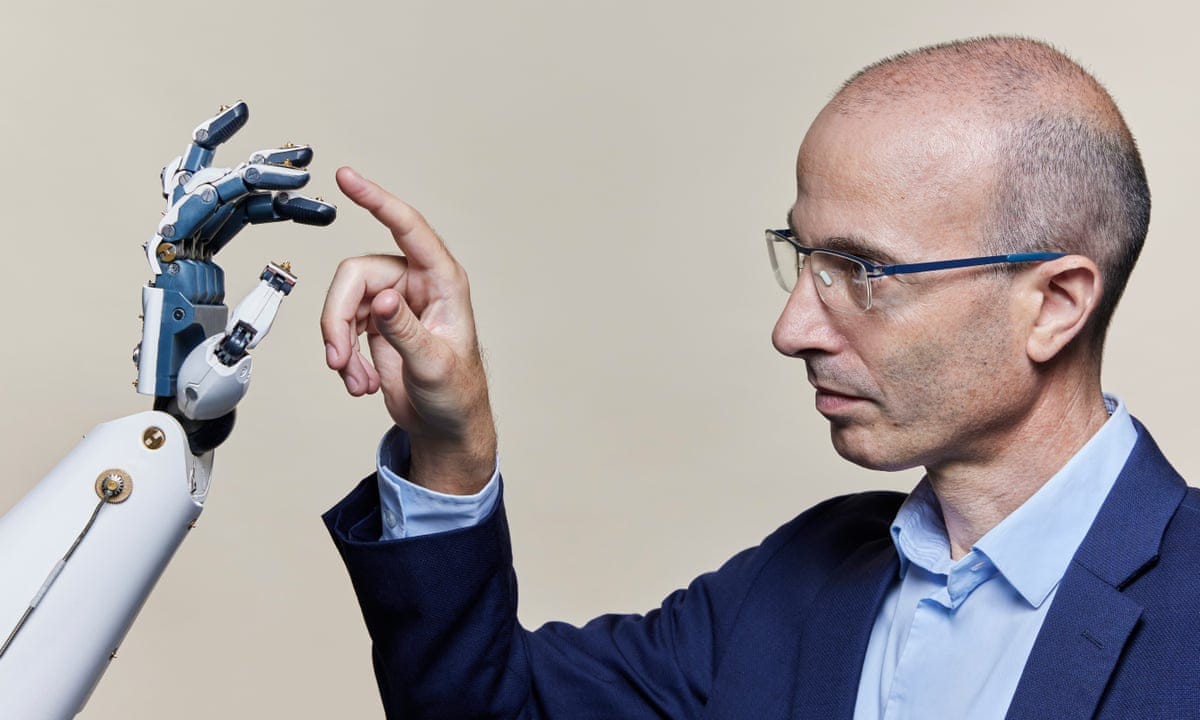

Maybe the feminists and social justice warriors aren’t driven by a gnostic impulse, but what about the transhumanists who share the gnostic desire to transcend the material constraints of their body altogether? Modern liberalism is animated by the desire to free the self from all constraints and collective identity. Some, like early transgender activist Martine Rothblatt, have spelled out the transhumanist turn implied by this impulse in books like “From Transgender to Transhuman: A Manifesto On the Freedom Of Form.” Respected liberal thinkers like Yuval Noah Harari talk about their liberal philosophy of individualist hedonism reaching its fulfillment in a transhumanist future where human minds can be uploaded to the cloud and exist in a state of perpetual pleasure and novelty.

Richard Storey, in a response to me on this topic, identified this as rooted in gnostic metaphysical assumptions:

The gnostic liberals do have a teleology, an end for human existence — it is the mastery of nature. Again, this belief is transcendent and makes metaphysical assumptions about the mind, destiny etc. whether the liberal realises they are engaging in metaphysics or not. Transhumanists believe that we can and will escape the shackles of this material body, and thus escape death, preserving our souls and transcending to create our own meta-worlds; not just augmenting this reality but subordinating the resources and tools of the material world to our own virtual worlds; not storming heaven but inventing our own as gods.

…

Now, I am of course not saying I believe this is good or even possible, but they believe it, and such a belief is unmistakeably a sect of gnosticism.

I might be provocative and say that thinking the experience of the boundless ego experiencing novelty in perpetuity is anything like the kind of liberation from corporeality the gnostic sects had in mind only reflects the poverty of our own modern view of the spiritual. It is quite common for moderns to view concepts like eternity as an infinite succession of events, and heaven as an infinitely pleasurable series of these events. From that perspective, the transhumanist dream of infinite jest in the cloud might seem similar, after all, didn’t the gnostics too talk about liberating the “pure intellect”?

As Hart observes, the transhumanist’s dream would have struck ancient Gnostics as a nightmare — the very image of hell. These spiritual sects did not want to “escape the material world” for a more complete hedonism or mastery of nature, as Storey suggests. Rather, they sought a radical severance from the very conditions of becoming altogether — time, matter, individuality, and desire. A less materially constrained, more physically liberated ego, as something which masks the inevitability of decay and suffering in this world, would be seen as a hindrance to the gnostic end goal. The soul’s end in the gnostic worldview is to awaken from the game entirely, not play it with better equipment. In the transhumanist vision, we are not simply caught up in the play of the shadows on the cave wall, but transform our own selves into one of the shadows and mistake this for liberation.

If a rejection of the material as a place of ultimate fulfillment and a desire for an infinite, incorporeal existence through spiritual “gnosis” is actually the spirit of our age, then it shares this with the innumerable spiritual traditions, and Harari and Rothblatt are the expression in our age of what the Buddha or Meister Eckhart expressed in theirs. Gnostic immortality was no endless extension of life — it was escape from life itself. A yearning not for more sensation, but for the Real: communion with God, a return to the silent divine source from which all being had tragically fallen.

In the end, the conservative habit of labelling wokeism as a revival of Gnosticism tells us less about the nature of woke ideologues than it does about the intellectual reflexes of their critics. It reflects a desire to give metaphysical weight to political opposition and lead us inevitably to finding the answer in their own religious and political priors. Unwilling to confront or defend the possibility of real and profound biological differences between groups — differences that might naturally produce the disparities woke activists interpret as signs of hidden injustice — these critics instead reach for metaphysical analogies. This allows them to redirect the debate toward familiar conservative anxieties like the decline of religiosity and and the excesses of intellectual radicalism.

In doing so, they avoid the unpopular task of challenging the real taboos at the heart of the debate, replacing it with a theological drama that flatters their worldview but explains very little.

Yeah, I always thought this was a pretty stupid way to go about messaging. Especially someone as smart as Feser should not be engaging in this, even if he does point to some superficial similarities. The thing is a) even with some (fewer than there are differences) similarities in how they view human nature, only James Lindsay is annoying enough to try and actually say they're one in the same and are genealogically related so why bother pointing it out and b) it being "gnostic" in some ways doesn't make it false, nor do most people even care if it's gnostic. Attack it's veracity, not it's imagined shared characteristics with ancient religions. Good article.

"In fact, if the apostles of woke have a metaphysical disposition at all, it’s much more optimistic than Feser et. al portray. Far from rejecting the material world, the woke think we can create a worldly paradise if only we can extirpate inequality and discrimination."

This is the crucial difference between leftism and gnosticism. Leftists are materialists and optimists through and through. They are levelers who want to flatten the cosmos down into raw sensuality and material factors, eliminating the spiritual and hierarchical dimension altogether. The leftist parody of theosis is to tear down the "idols" of any kind of higher authority intermediate between God and man so that everyone can become relatively divine by having nothing above them. It is more of a heresy deriving from the protestant impulse than anything to do with Gnosticism. It's actually the opposite of what the gnostics were trying to do, which was to accomplish a segregation of the material from the spiritual, strengthening the hierarchy.

It's true however that Gnosticism has a satanic, antinomian undercurrent to it. There's a kind of horseshoe effect where if you see the spiritual as reducible to the material you disenchant the world, but if you see the spiritual as too divorced from the material then you end up back at just disenchanting reality again because the spiritual is inaccessible. Because they see this world as the creation of the Demiurge, and not the ultimate God, Gnostics tend towards extreme pessimism and life-denial. If this world is entirely severed from God then it is of no consequence to the moral life whatsoever, and like leftists Gnostics come to see all existing power-structures as manifestations of darkness. Recently, the leftists have even come to support the power-structure through a strange inversion, whereas Gnostics, even more than anarchists or libertarians, have a consistent suspicion towards all forms of power. You can see this for example with David Ike, to my knowledge the most influential modern gnostic.