Big news this week: the EU Commission fined Elon Musk’s X platform for 120 million euros over its failure to abide by the Digital Services Act. Specifically, the EU has accused X of deception because of its new Premium badge system, where any user can get the blue tick just by paying for premium; and for withholding data from researchers. Given that this is the first time the DSA has been used in this way, this is an ominous ruling. Musk said last year that the impositions of the act may in the long run make it unviable to stay operating in the European Union.

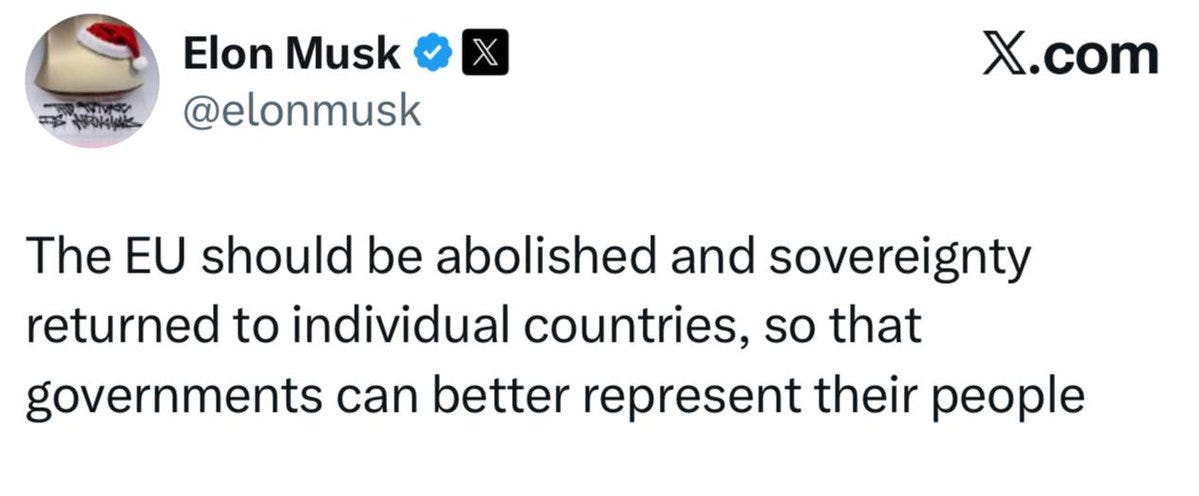

In a style that has become typical of Elon’s approach to politics, he lashed out against the EU with a call to tear the whole thing down, and abolish the European Union. Prominent American politicians like J.D. Vance and Marco Rubio have been extremely critical of this ruling, coming in the same week a new U.S. Security Strategy claimed Europe is becoming a minor actor on the world stage due to its commitment to failed mass-migration policies. Some identitarians in Europe, like Martin Sellner, have jumped on this opportunity to argue the case for abolishing the European Union as the body facilitating the demographic replacement of Europeans. Should we all get behind this push? I am skeptical.

I’m sure it will be surprising to some readers to see me push back on this. First, I am a nationalist. I believe the best kind of states are ethnostates, and a good moral principle on which to base a sustainable international order is a right of self-determination for national groups. The EU’s leadership is opposed to ethnonationalism and seeks to undermine the sovereignty of its constituent members toward a globalist, social-liberal agenda. I also support the idea of subsidiarity — that is, governance should operate on the most local and immediate level possible — and I think a great many problems of the modern world would be solved by more decentralisation (I am so sure of this, I am currently working on a book on this topic.) The EU nominally supports this, but in practice its evolution has been a steady ratcheting of authority away from national and local government toward Brussels.

Clearly, a European nationalist cannot support the current EU. The fine against X is only the latest example of overreach by a bureaucracy that has long positioned itself against populism and national expression within the Union. From its inception, the Union was designed by anti-national technocrats with the aim of undermining nationalism, especially German nationalism. Its central institutions were built with the deliberate intention of placing key decisions beyond the reach of national electorates, insulating policy from the populations it purported to unite.

Yet none of this straightforwardly commits us to the conclusion that the Union should be torn down, or that even if that is desirable, that we should direct our political energies there as nationalists with the limited time we have to turn our countries around. Politics is the art of the possible, and it would be bad strategy to tie a very winnable position to a more ambitious one with little support. The most important thing for nationalists right now is creating the metapolitical change to normalise opposition to replacement migration on racial/ethnic terms, and in turn normalise and generate support for the remigration. This is an achievable goal, and we have seen great strides in that regard in recent years.

Abolishing the EU is not a popular position. According to a poll conducted this year, 74% of Europeans think their country has benefited from EU membership. Only 6% opposed the idea of the Union on principle. Even in countries where a majority feel the EU is going in the wrong direction, like Italy and France, only 27% would vote to actually leave the Union. Even a majority of right-wing voters don’t support this in most countries; for example, only 36% of supporters of Spain’s Vox party would vote to leave.

An irony of these fresh calls emanating from our friends in the United States is that the American right’s attacks on the EU often end up bolstering the very Europhiles they hope to weaken. Liberals can reframe their defence of the current Union as a proud European stand against boorish American meddling, portraying their deference to globalist technocrats as the truly self-confident European stance. There is a risk that U.S. criticism gives Brussels the continental legitimacy it can’t actually generate on its own. This only deepens the basic problem: abolition is not just unpopular, it is easily caricatured as an American import rather than a European demand.

So the first problem with this proposal is its unpopularity. The constituency that supports leaving the EU already overlaps almost perfectly with those who support sweeping reforms on immigration and national sovereignty, but almost everyone who isn’t already on board with those things associates exit with uncertainty, political chaos and potential economic ruin. The example of Brexit has not put anyone’s mind at ease in this regard, and the massive number of non-European immigrants Britain has welcomed since has made it harder to claim that departure from Brussels is a reliable tool for national self-correction.

And that brings us nicely to the next point: the EU is not the chief obstacle to sensible immigration policies. Immigration policy is still set by our national governments, and were there a will among them to do so, they change course. Countries like Poland and Hungary show ethnostates can still exist within the EU with strict immigration policies, while countries like Denmark and Sweden have begun experimenting with remigration programs. Often, directing blame for mass, non-White migration towards the EU is just misdirection for people who blame far-away, globalist bodies for what is happening in their country because of their own political consensus. For years, populism in Britain was directed toward the single cause of leaving the European Union, which delivered multiple Tory governments majorities to “get Brexit done,” in which time they oversaw record net-migration to a bemused voting base.

Given how fine the margins are for nationalist parties on the verge of power in Europe, in most of the continent it would be effective political suicide to commit to a hard stance of Eurexit while the populace is so against it, tying a potentially majoritarian project to a peripheral cause. And nothing would make nationalists more unpopular than attempting this grand project and failing.

A third problem is that even if public opinion shifted, the practical work of dismantling the Union would be a generational undertaking. The EU is not a single treaty one can rescind but a massive interlocking architecture of legal, economic, and regulatory systems woven into every member state’s daily functioning. Undoing this cannot be done overnight, and any attempt at immediate abolition would produce a level of administrative and economic dislocation that no responsible movement should inflict on its own societies, if for nothing else than its own political survival.

A botched attempt — one that failed to overcome the many legal obstacles, or the certain market panic it would trigger for our already heavily indebted nations — would not simply fail; it would permanently discredit the parties that championed it. Nationalist movements that are now on the verge of governing in several countries would find themselves blamed for the resulting chaos, economic downturn and instability, giving a new lease of life to the reliably stable Europhile establishment.

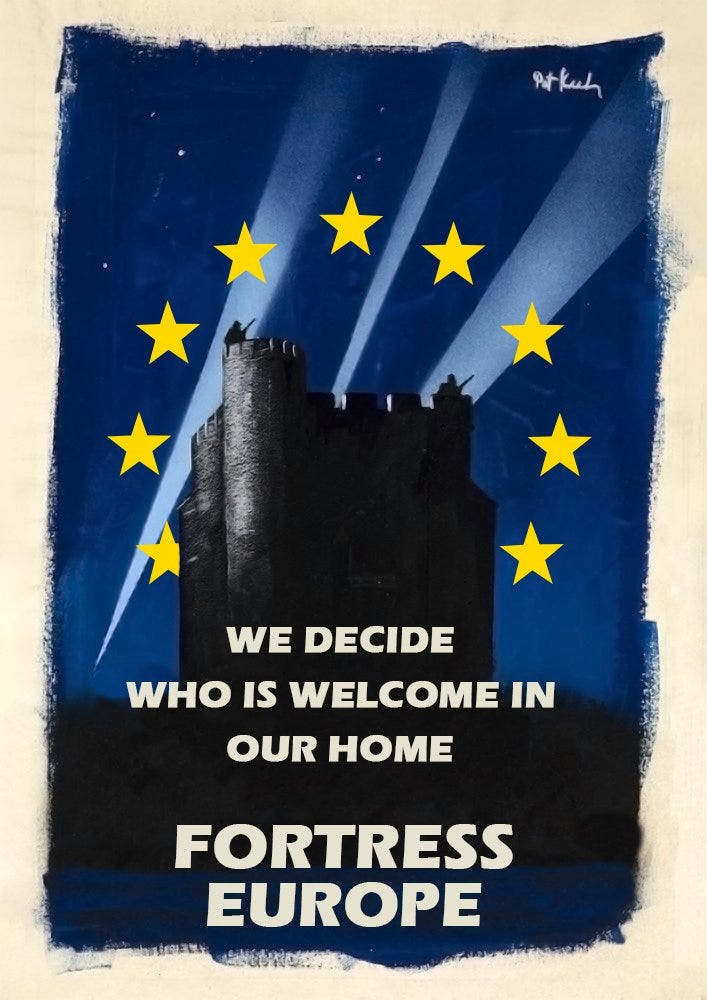

Lastly, there is a certain irony in the claim that electing governments willing to abolish the EU is a prerequisite to saving Europe. Because if the day comes where nationalist parties do command enough public support across the continent to make abolition a realistic prospect, they would by that very fact also possess the strength to reform the Union in the direction we want anyway. In other words, if you can build a political bloc capable of dissolving Brussels, the same bloc is capable of redirecting it to a vision of Fortress Europe. The level of support required for abolition would already guarantee the possibility of meaningful reform, without the upheaval of tearing the entire system apart and committing us to mapping out an unpopular and potentially perilous course.

A competing vision

While I am skeptical of the wisdom of pushing to “abolish the EU,” the principles underlying the drive are good, and it’s not very inspiring to tell idealistic nationalists that they must simply accept the reality of an institution hostile to their interests. Instead, we need a new, inspiring vision of how the Union could be scaled back and remade in a way that actually treats the preservation and flourishing of the distinct European peoples in a multipolar world as its guiding mission. Away from the centralising bureaucratic economic union of the EU technocrats, we should look to the European example of Switzerland as a union that has endured centuries and fostered the constituent identities of its diverse people groups.

Although its system of Cantons sounds positively medieval, the Swiss model has shown remarkable resilience in the modern era. Switzerland is a world-leader in a number of economic and social metrics, often ranked at the top of rankings of global competitiveness, innovation and quality of life. Yet it has achieved this while weathering the worst effects of globalism and maintaining a great deal of local autonomy. Switzerland’s decentralised model has been successful because its cantonal governments can innovate, correct mistakes quickly, and tailor policies to the specific needs and strengths of their own regions and people. No region feels trapped under the authority of a distant centre, and no central authority mistakes its role for that of an imperial administrator. In other words, the Swiss model has escaped many of the problems that plague the modern European project while maintaining the benefits that larger cooperation can bring, especially in economics.

It’s easy to forget now that subsidiarity was supposed to be a central governing principle of the EU, because it is totally irrelevant to how the current Union functions or how its leaders conceive its purpose. A reformed Union, one led by strong and independent nations, would recover subsidiarity as the structural logic of the entire project, returning authority to national and regional governments while maintaining a pan-European architecture for strategic necessities. But even this continental scope of action — when conceived as a protective framework that shields Europe’s constituent regions and coordinates their defence on the world stage — aims at the flourishing of European culture all the way down to the most local level. A Europe that defends its civilisation collectively makes it possible for its nations (and its regions and smaller communities) to live and develop on their own terms.

A confederal Europe led by patriots could also be advantageous in doing something modern nation-states have failed at — empowering more local regions and cultures with a greater degree of independence. These more independent regions could govern closer to citizens, more attuned to local needs than national governments, and far better placed to preserve their cultural distinctiveness. Under the leadership of proudly European nationalists, this project would not have to undermine or weaken nations. Instead, it could anchor them in their natural historical foundations and produce a more vibrant Europe with many centres of vitality, well attuned to Europe’s natural diversity. Were this to be achieved, the homogenising pressures of governance by distant, cosmopolitan managerial elites would be structurally undermined, and with it one of the great pressures driving our continent leftwards.

Ultimately, the question is not whether the EU should change, obviously as it exists now it is terminally at odds with genuine European nationalism. The question is what is the viable path to undo its nefarious aspects. A movement strong enough to abolish the Union would be strong enough to reform it, and reform could offer us the tools we need to undo our erasure without gambling our people’s survival on a highly fraught, unpredictable course. Given the high stakes with which we are playing, it’s wiser to focus on building what will last than to roll the dice on rupture.

This is the take I've been looking for . As a nationalist myself , the idea of multiple countries of similar political persuasion controlling the EU fills me with a hope I'd almost relinquished. This is the correct path . Excellent work Keith

The priority of nationalists should be to experiment with ways to help their families, neighbours and local communities organise to survive the coming liberal collapse clusterfuck.

Nationalists must stop pretending that we can push or pull the liberal capitalist elite or the populist capitalist alternative to fight and win the devastating civil war that would be needed to impose remigration.

Refusal to face facts is either folly or cowardice.